George M. Cohan

2013 INDUCTEE

Composer/Musical Theater

THE RHODY COLOSSUS

by Gerard H. Heroux

Some great musical talents have been Rhode Island born, while others have been Rhode Island bred. And some who’ve lived and died here may well be “Rhode Island dead” (to paraphrase the URI Fight Song). And while it is the goal of the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame (Hope Artiste Village, 999 Main Street, Pawtucket, RI 02860) and its associated website to celebrate the achievements of all talented Rhode Islanders – born, bred and dead – we might consider removing from the wall the plaques of all those great born, bred and dead RI talents already inducted into the Hall of Fame, we could take down every article from the website, and with one major exception we could cease honoring anyone else from now on. We could do all these things and we’d still have a valid cultural institution – we would simply dedicate all available resources to a museum of and about the most famous, and the most significant of all the great RI talents, George Michael Cohan (1878-1942) – a man Rhode Island born, only slightly Rhode Island bred, but most definitely not Rhode Island dead.

For a start, this museum could have continual screenings of both “Yankee Doodle Dandy” the 1942 Hollywood movie musical based on Cohan’s life starring James Cagney and “George M!” the 1967 Broadway musical that launched the career of Joel Grey. On display would be a sampling of the many elementary school music books that for over the past half-century have included Cohan’s music – especially his patriotic songs like “You’re a Grand Old Flag.” There could be concerts for St. Patrick’s Day featuring his Irish themed songs like “Harrigan” and “Mary’s a Grand Old Name.” Of course there’d be Fourth of July band concerts featuring medleys of his greatest hits.

The museum could host scholarly seminars on the cultural and historical importance of Cohan’s achievements – after all Cohan’s “Over There” stands as one of greatest propaganda songs of all time, being the virtual recruitment song for the United State’s entry into World War I. Not to mention, he also wrote the theme song for a life in the theater and in the process wrote one of the greatest New York City songs: “Give My Regards to Broadway.”

Cohan was as famous in his day for his playwriting as he was for his music; in fact he had equally great successes with both musical and non-musical dramatic plays. Perhaps a revival of his stage works could be sponsored by the museum, with associated exhibits on display focusing on his business acumen, showing how he owned and ran several theaters in New York, produced and promoted his own plays, and published his work along with the works of others. That these activities put him in conflict with then newly formed Actor’s Equity union during the 1920s could also be a great avenue for scholarly discourse and exhibition at this Cohan museum.

And the man could sing and dance! Exploring the influences of 19th century American song and dance on Cohan and in turn all the 20th century song and dance styles influenced by him should keep museum curators and scholarly researchers busy for years to come. Oh, and one more thing – you could talk taxes at the museum because of the Cohan Rule, a 1930 legal decision made in George’s favor that allows a taxpayer to estimate the value of income tax deductions with the IRS even without specific documentation, as long as it can be proved that the expenses deducted are reasonable for the type of income generated.

No one else from RI – or from New York, I’d hazard to say – can lay claim to these accomplishments. He was indeed a colossus. But fear not – we won’t be removing all the competition from the Hall of Fame walls and website just yet (as much as that would have pleased the typical George M. stage persona – though the real Cohan would have reinstalled everyone at his own expense). Instead, let’s delve into this man’s story, which starts from a little corner of Providence known as Fox Point.

So listen, kid…

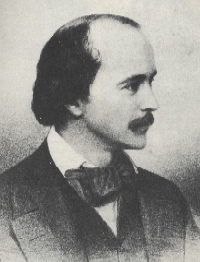

In June of 1878, at 536 Wickenden St., one Mary Ann O’Hearn welcomed her pregnant cousin Helen Costigan Cohan, whom everyone called Nellie, into her home – just as she had done two years earlier when Nellie was pregnant with her second and up to now only surviving child, Josephine. On July 4th (or July 3rd if the baptismal record of nearby St. Joseph’s Church is to be believed) George Michael Cohan was born in that O’Hearn house on Wickenden St., situated at the edge of Corkie Hill – a former nickname for Fox Point’s Irish immigrant section – the third and last child of itinerant theatrical performers Nellie and Jeremiah (Jerry) Cohan.

Fox Point 1880 viewed from East Providence side of the river - the large white building in the top center of the picture is the Providence Reform School (demolished in 1886), seen to the right of the school in the near background is the square steeple of St. Joseph Catholic church where George was baptized. George's birthplace is two or three blocks to the right of the school near the corner of Wickenden and Ives Streets. The preset day George M. Cohan Boulevard runs from the left of the school past the still standing Tockwotton Home for Women alongside route I-195. India Point Park today comprises much of the waterfront property in this view. Photo posted to Flickr - courtesy of Don Costa.

Jerry Cohan, a second generation American of Irish heritage, a Civil War veteran, and a one time harness maker from Boston who found a livelihood acting, singing, dancing, playing harp and fiddle in city theaters and wayside community halls as part of a troupe of Irish performers traveling up and down the East Coast, and not infrequently into the Midwest. Jerry’s sister, who lived in Providence, wrote to her brother telling him about a neighborhood girl whom he might like to meet. Nellie Costigan was a lively girl, who was a talented mimic and storyteller, who also was patient and practical – a good match for a minstrel man. They met, he courted her, she accepted his proposal and they married in June 1874.

Without a honeymoon, Jerry and Nellie immediately hit the road as part of a Hibernicon, an Irish-styled vaudeville of songs, dances and sketch comedy. Jerry in addition to performing would write some of the sketches, he would also handle the business organization of the troupe and Nellie would be the ticket seller and ticket taker.

Eventually, after one of the lead actresses quit the troupe, Nellie stepped in as one of the performers – she knew the lines well enough after hearing so many performances so it was a natural progression for her. However, it wasn’t long before Nellie had to return to Providence due to becoming pregnant with the first Cohan baby, Maude, who only lived for nine months.

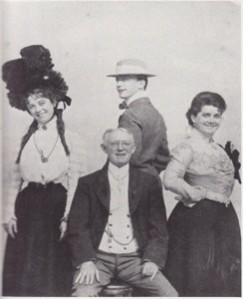

After that sad event Nellie threw herself wholeheartedly into her husband’s profession and she and Jerry worked up a duo act billed as “Mr. and Mrs. Jerry Cohan,” which they parleyed in an Irish variety show called The Molly Maguires, for which Jerry eventually became the manager. Once again Nellie, pregnant with Josephine, returned to Providence, staying with her cousin until the child was old enough to take out on the road. And this pattern was repeated after George was born. Eventually both Josephine and George went to public schools in Providence when they were old enough, staying with relatives in the Fox Point neighborhood.

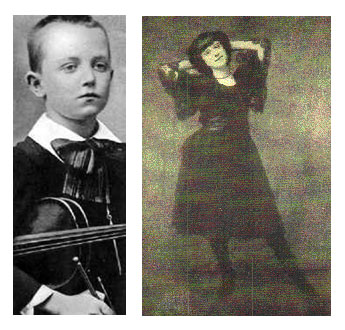

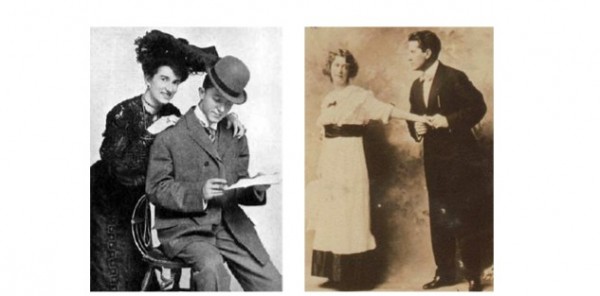

But George struggled in first grade, and he was moved to a different school for his second year, then Mr. and Mrs. Cohan took George and Josephine (by now called “Josie”), at the ages of eight and ten, out of school for good. Josie who had talent as a dancer and George who had some talent as a violinist were both gradually inserted into the family’s troupe – Josie on stage as “America’s Youngest and Most Graceful Skirt Dancer” and little George in the pit playing second violin. Incidentally, “skirt dancing” was a type of balletic stage movement for women in specially designed, long white skirts that they would extend out and gently wave with their hands, frequently illuminated by colorful lighting, popular in the late 19th and early 20th century in England (where it originated) and America.

George, who throughout his life admitted to being stage struck, didn’t want to be left out of the spotlight. He worked up an act of “violin tricks,” no doubt consisting fancy fiddling and sound effects, and he also worked up a dance routine around being a shoeshine boy. The shoe shine act seemed to go over better than the violin tricks so eventually George’s violin was permanently set aside and his dancing shoes were more or less to remain on his feet for the remainder of his life.

Bell Street, the Irish part of town in North Brookfield, MA photographed in 1903 by Theodore Wohlbruc.

In 1893, when George was fourteen, M. Whitmark and Company published his first song “Why Did Nellie Leave Home?” (Mr. Whitmark being a fan of the Cohans from their occasional New York appearances). Sales proved good enough for publishers Spaulding & Grey to take on a second effort by George entitled “Venus, My Shining Love” which became popular with singers in New York and a steady seller (and one of George’s personal favorites of all his songs). Reubling and Beil in their Parlor Songs Academy website make a convincing argument that George was hired by Spaulding & Grey to Americanize the lyrics of this and other tunes from an English publisher and it is not actually a Cohan original.

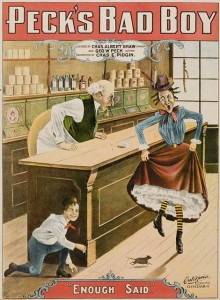

By this time George had already been acting in a lead role when the Four Cohans were engaged to join the cast of a traveling show, “Peck’s Bad Boy.” Starting from New York in 1891 this show went across the country for over a year, and George more often than not had to fight his way out of the theatre facing local boys who wanted to see just how bad “Peck’s Bad Boy” really was. This has been credited to contributing to George’s pugnacious personality.

The other aspect of George’s personality, which frequently caused problems for The Four Cohans, was that he had no compunctions about speaking his mind. He had a natural instinct for what worked on stage; even at a young age he had the experience to back it up. He would constantly make suggestions for improving “Peck’s Bad Boy,” making his complaints known, especially about what he considered to be bad lighting. This coming from one so young would make enemies with other cast members, crew and management. As much as his parents tried to control him, there would always be another episode and as often as not George would be right – which probably made the situation worse.

By the summer of 1892 The Four Cohans were let go from “Peck’s Bad Boy” due to George’s constant complaining about the production. So the family went back on the variety circuit with Josie’s graceful dancing, becoming more and more the star attraction. It was during this time while The Four Cohans had some down time in Buffalo, NY that George joined the cast of a local company performing musical plays by the Irish composer and dramaturge Dion Boucicault, whose quick paced action interspersed with pleasantly sing able songs inspired George to begin writing longer comedic sketches and one-act plays. It was Boucicault’s work that would prove to be the model for much of George’s creative output for years to come.

The Cohans spent the remainder of the 1890s developing longer dramatic vehicles for their talents, mostly written by Jerry but increasingly written by George. Josie was getting more and more dancing work independent of the group causing a certain amount of strain on the family dynamic. In addition there was tension between father and son due to Jerry’s reluctance to showcase their new shows for New York City audiences, feeling that they were better suited to the less exacting hinterland audiences. In the early summer of 1893, George was threatening to leave the group and make his way in the Big Apple as a songwriter and as a writer of sketches for other theatrical companies, and hopefully as a stage performer. But as it turned out The B.F. Keith agency had an opening for The Four Cohans at Keith’s Union Square Theatre in Manhattan that August. So George stayed on, but what seemed to be so promising booking turned sour as Keith wanted the Cohans to perform their song and dance pieces and not the piece they were preparing (Jerry’s “Goggle’s Doll House” an audience favorite with George and Josie as dancing dolls). Keith split the booking so that George had the dreaded opening slot, which infuriated him to no end. The family struggled through the Union Square stand with Josie generally getting the best response from audiences and critics and George hyperactively trying to capture the attention of people noisily wandering into the theatre to take their seats, some reading their newspapers.

It was at this low point for George that Jerry made the fateful decision to turn all of the Cohan business and bookings over to his son, who being the most aggressive of the four, managed to get the family back out on the road. These were hard years of playing to half full houses, but they never lost hope with George in charge and eventually they came back to a successful New York run at Hyde and Behman’s Theatre, Brooklyn in 1896. This booking propelled the Cohans into the upper echelon of vaudeville acts, making them the highest paid entertainers of their time at $1000 a week. The family was now primarily doing George’s sketches such as his Money to Burn, The Governor’s Son and Running for Office. George’s goal was to expand these one-acts into full-length musical productions and put them up in the legitimate theatres (as opposed to vaudeville).

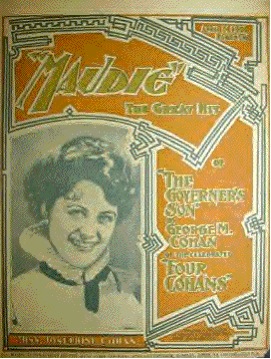

After five years of trying things out, making changes and developing confidence in the presentation, The Four Cohans had something to offer Broadway with The Governor’s Son, a comedy about the comings and goings of various romantic couples at a resort inn, including a son of a state governor (George) who is pursued by two women, one of them a “man-hungry” widow. There were roles for all four Cohans plus one more, George’s new wife Ethel Levey, a talented singer/comedian whom he married in 1899 after a lengthy courtship (conducted mostly by correspondence). And a year later George himself was the father of a baby girl named, appropriately enough, Georgette.

In 1901 Josie too got married, and like her sister-in-law, Josie’s husband was a fellow performer – Fred Niblo, a comedian monologist, who also managed Josie’s promising solo career, a career which threatened to break-up the original “four act.” But as each new opportunity arose for The Four Cohans, and each time new professional levels were achieved, Josie would always returned to the fold, essentially putting her career on hold for the family and at the same time making Ethel feeling like a “fifth wheel.” This was a source of friction between Ethel and Josie – and it had consequences for Ethel and George’s marriage.

With money put up by L.C. Behman, The Four Cohans, Ethel Levey, and a large cast played The Governor’s Son at the Savoy Theatre in New York, but only for thirty-two performances despite some favorable reviews. So back on the road they went for another two years, revising The Governor’s Son and expanding George’s Running for Office (which had players running on and off the stage in constant motion – something novel at the time). They returned to New York in 1903 to showcase Running For Office, this time backed financially by Josie’s husband, Fred, but once again only for a limited run.

Sheet music for one of George's songs from The Governor's Son (misspelled on the cover) featuring a photo of Josie.

The Colossus Rises

By 1906 George was ready to try something different, something that would put more focus on him as a leading man. After reading about a famous New York jockey, he thought that a musical play about horse racing might provide a good leading role for him, considering his short height and skinny frame. As a jockey he could portray an adult (as opposed to a governor’s juvenile son) and be realistically athletic enough to break into song and dance. But what kind of musical could be made out of horse racing? He needed something more. Well, with George’s patriotic inclinations – due no doubt to his supposed 4th of July birthday – it didn’t take long before he made a connection between the song “Yankee Doodle,” with its lyrics about going to London to ride a pony, and being a horse jockey. This connection provided the framework for a story about a young, all-American jockey going abroad to race in the English Derby. And so Little Johnny Jones was born, a show that contained two of George’s greatest songs “The Yankee Doodle Boy” (which actually has the “Yankee Doodle” melody and lyric dropped into the end of the chorus) and “Give My Regards to Broadway.”

At this time, while promoting his new show, George met Sam H. Harris, a young man of varied occupations then currently managing a lightweight boxer George had just bet against. Sam loved the theater and was looking for a way to get involved in producing shows. He and George hit it off so well (in spite of George’s bet against his client) that they agreed to form a partnership. As it turned out Cohan and Harris became one of the most successful producers on Broadway for the next fifteen years, with Sam handling the business side and George developing the creative end. They both were involved in reviewing the works of other playwrights (Sam had a great instinct for what would succeed on Broadway), which they would then produce (often with re-writes from George).

For their first venture, however, Cohan and Harris barely managed to get Little Johnny Jones off the ground. Yet when it finally opened in November of 1904, they knew they had something good to offer the public and despite a limited run of 54 performances, they revived it twice in the following year, each time to more acclaim. Then they took it out to where the real money was to be made, in theatres across the country. Along for the ride were George’s parents, with roles specifically written for them, and Ethel, with a fine showcase for her comedic talent in three different characters (including a pants role – masquerading as an English lord). Josie, however, and her husband were not part of Little Johnny Jones, having joined the cast of another New York play with the goal of establishing Josie as a star in her own right.

With this latest offering, New York’s theatrical community took notice of George’s success with middle class audiences. He had a natural affinity for the easy language and brisk tempo of a youthful, unaffected America. And his songs had a catchy simplicity that seemed to say what his audience was feeling and thinking. This was new for Broadway in the early 1900s which typically presented frothy Viennese styled operettas, upper class parodies in the Gilbert and Sullivan mode, and melodramas with grand operatic pretensions, weighted with the stately rhythms of the previous century.

While the middle class found in George M. Cohan a mouthpiece for their hard earned comforts, the dreams and aspirations of the poor and disadvantaged had yet to find a voice on Broadway. But a change was coming, because bubbling under the surface of the entertainment mainstream and running its own separate course in black vaudeville and urbanized minstrelsy was the dynamic joy and sarcastic wit of African American music, dance and storytelling. Ragtime, blues, swing – and a grittier sense of drama – especially when filtered through composers and playwrights of Eastern European Jewish heritage – were still some twenty years away in terms of their influence on the theatre of “jazz age” America. And here was George M. Cohan, in his own New England Irish cocksure way, opening the door for this new Broadway during the first decade of the 20th century – but it was a door he couldn’t actually pass through himself when the time came (as you’ll see soon enough, kid).

Growing Pains

Yet for all the early adulation, George was not exactly a critical favorite, though he had his champions both in New York and across the country. There were critics who thought he represented a deplorable lowering of standards. (How some things never change!) They said that the lead characters – George’s roles, usually – were merely smart alecks who spoke slang. They also said that there were no strong female roles in his plays (and by and large they were right on that score). They claimed the plots were simplistic and the songs were obvious (frequently made up of phrases of other pre-existing songs). In short many critics felt that a Cohan show was just a step above vaudeville.

As a rule George ignored bad reviews, even when the criticism was justified, however a 1905 review by the Providence Journal’s Frederick H. Young got George so upset he vowed never to play the city again. An otherwise enthusiastically received Providence performance of Little Johnny Jones, before an audience with many friends and family in attendance was described by Young as a “musical melodrama,” “uneven,” “ill-assorted” and “commonplace.” Worst of all, he made fun of George’s nasal singing and speaking voice.

Many years later, Young defended his comments by saying he had no personal grudge against Mr. Cohan, he just didn’t think the show, and George’s performance, was worth twice the admission price of The Governor’s Son, which he had seen in Providence – and enjoyed, giving it a glowing review – a few years earlier. But for the next six years George was true to his word and Providence was removed from the itinerary of all Cohan and Harris productions, with city and state becoming the occasional butt of jokes in several Cohan plays.

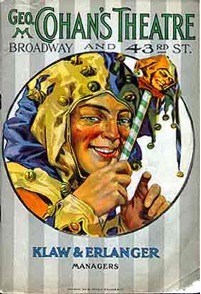

As Little Johnny Jones exploded during its 1905 run, Abe Erlanger, of theatrical producers Erlanger and Klaw, got excited by this new direction George was developing for the musical theatre. And while George could ignore the theatre critics, he respected the opinions of the theatre managers and producers. (Outside of immediate family, his fellow actors were not generally part of George’s social orbit, as he aligned himself more with the “money” of Broadway). So when Erlanger approached George with the idea of writing a show for two of his star performers, Fay Templeton and Victor Moore, he jumped at the chance – even though he just started the partnership with Sam Harris – and the result was one of George’s most beguiling creations.

Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway, as it was eventually called (George wanted “Mary” for the title but Erlanger thought otherwise), could be considered the first suburban comedy – with characters living in New Rochelle, a small town just outside New York City. The plot concerns a maid who is set to inherit a million dollars from her recently deceased employer but is thwarted from doing so by relatives from the city. It’s a musical with songs well integrated into the story, featuring two of George’s best – the title song “Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway,” and “Mary’s a Grand Old Name,” one of his loveliest Irish-themed tunes.

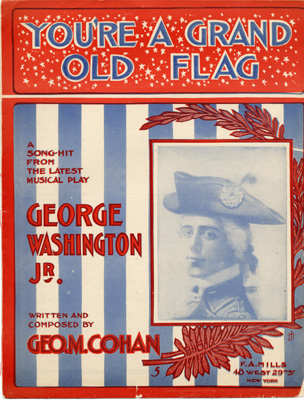

For his next Cohan and Harris production George wrote George Washington, Jr., a romantic farce with action centered on Washington, D.C. It was sprinkled with patriotic numbers like the show’s big hit, “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” and it had plenty of jokes about crooked politicians to keep the audience amused. George wrote parts for his father, mother and his wife (but sister Josie, did not participate in the Broadway run). Of course George played the title character and he got to sing the big song – though Ethel had a hit with “I’m From Virginia,” a song that became so associated with her, it was frequently credited on phonographic recordings and sheet music as “Ethel Levey’s Virginia Song.”

It’s interesting to note that “You’re a Grand Old Flag” (originally titled “You’re a Grand Old Rag” but altered due to complaints from audience and critics) contains another musical insert towards the end of the chorus, yet that insertion’s connection to the rest of the song is not as apparent as it is in “The Yankee Doodle Boy.” The melody and words of the insertion are from the opening phrase the Scottish song “Auld Lang Syne,” a tune closely associated in this country with New Years Eve celebrations. When heard outside of its dramatic context it seems a random, if not surreal, choice of material. But on stage the concept makes sense. During the play, just before the song is sung, an old, grizzled Civil War veteran hands George a lovingly folded, battle-scarred American flag, proclaiming, “She’s a grand old rag!” This is where “Auld Lang Syne,” meaning literally “old times passed,” comes into the picture – its sentimental associations making a fleeting comment on the soldier’s memory of comrades and glorious days gone by. It’s a subtle touch (if subtle is the right word for such a rousingly patriotic song) for which George M. Cohan, as a composer and lyricist, often is not given credit. Of course the fact that the insertion trick worked so well for “The Yankee Doodle Boy” was probably not far from George’s mind during the writing of this essentially similar follow-up.

For the remainder of the decade and well into the next George had four productions either on Broadway or on the road, The Governor’s Son, Little Johnny Jones, Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway, and George Washington, Jr. It was during these, the most creative and successful years of his career, that George wrote several more theatrical works, and he also found time to revise, direct and produce the works of others at theatres throughout the city and beyond (he and Sam Harris were part owners of several theatres in New York and Chicago). Eventually Cohan and Harris owned two theaters on Broadway itself, where George and Sam produced a string of steady, if not spectacular, successes with a mix of musicals, dramatic plays, and variety reviews.

In November of 1906 George tried his hand at writing a straight dramatic play. Popularity had a brief run despite some good reviews (mostly for the acting) and the employment of innovative stagecraft in using the actual backstage of the theatre as part of a setting for the second half of the play and calling for the audience to participate in the action on stage by applauding at a certain point. Unfortunately George did not act himself in Popularity because he was busy performing in George Washington, Jr.

Sheet music for the instrumental "overture" for Popularity later turned into a song. Sometimes referred to as "The Popularity Rag."

George never spent a lot of time writing any of his plays, he usually worked very quickly in condensed periods of activity, frequently late into the night. He tended to brush up against deadlines; in some instances he was still writing the second act while the first act was already in rehearsal. He encouraged a certain amount of improvisation from his actors during the rehearsal process (though not so much after all the kinks were worked out and the play was up and running). But even within the usual Cohan chaos, it’s quite possible that George had things on his mind, things that kept him from making a better play out of Popularity (though some years later George did convert this play into a successful musical, The Man Who Owns Broadway).

George and Ethel’s marriage, already a union of creative tension, had taken a turn for the worse during this period and in December of 1906 Ethel was granted a divorce on grounds of George’s infidelity while in Chicago. (Ethel had hired a private detective to keep an eye on George during one of his tours stops in that city.) This charge was assumed to be more of a convenient way for George to grant Ethel her freedom than any actual infidelity. And while there may have been cause for Ethel to suspect that George’s late night writing sessions had more going on than putting pencil to paper, the real reason for the breakup was that Ethel was too much like George in her desire to be in the spotlight. She could never be happily married to a man who worked so hard day and night to stay in that spotlight himself – and whose immediate family was sharing the spotlight with him – leaving little room for anybody else.

Ethel was granted custody of Georgette, the couple’s only child, whom she took back with her to California, her home state. Eventually Ethel went to Paris and then London, where she had great success on the stages of the West End. She married an English aviator and maintained a respectable career both in England and on Broadway. She retired from show business in the mid 1940s and died in 1955.

George, of course, stayed in New York near his beloved Broadway and in April 1907 – just four months after the divorce – he married Agnes Nolan, a chorine who, along with her two sisters, was dancing in Little Johnny Jones. The Nolan sisters were from a large family (eighteen children!) of Irish Americans from Brookline, MA – and being young girls all alone in the Big Apple – George’s mother, Nellie promised the Nolans that she would personally keep an eye on them. Agnes first attracted George’s attention when she negotiated with Sam Harris for a higher weekly pay rate than the going standard for a chorus performer. George probably recognized a bit of himself in that kind of gumption, and with the Nolan girls being in close proximity thanks to his mother’s stewardship, a warm friendship developed between him and Agnes.

George and Agnes remained married for the rest of George’s life (despite rumors of discreet affairs between George and young actresses) and they had three children together – Helen, Mary and George Michael, junior. The difficult birth of the last child left Agnes a semi-invalid, yet she outlived her husband by a couple of decades, living in relative seclusion until her death in 1972. Incidentally in 1909, two years after George’s and Agnes’ wedding, Sam Harris married Alice, one of the Nolan sisters, making George and Sam brothers-in-law.

Five of the Nolan Sisters pictured at Sam Harris' estate in 1924. Left to right: Alice, Grace, Lola, Agnes and Dorothy (Image from The Chicago Tribune, September 7, 1924)

With George’s personal life back on track, 1907 saw more hit Cohan musicals – The Talk of New York, featuring a reprise appearance of Kid Burns, one of the main characters in Forty-Five Minutes from Broadway, and Fifty Miles from Boston, a nostalgic look at Gorge’s summer vacation days in North Brookfield that featured one of George’s greatest songs, “Harrigan.” And 1908 saw the last play of George’s to be written for and performed by The Four Cohans (including Josie). Entitled The Yankee Prince, it was basically a rewrite of Little Johnny Jones with brash young Americans getting one over on the stodgy British.

The Years of Change

The next decade of George’s career, from 1910 – 1919 saw both its highest and lowest points. George finally achieved popular acceptance in 1912 as a legitimate playwright with Broadway Jones, a non-musical comedy (about musical comedies). It was the last of his shows to feature his parents, Jerry and Nellie, who at the end of the run announced their retirement from acting (and George too proclaimed his “retirement” from performing to concentrate on writing, directing and producing, the first of many such pronouncements throughout his long career). And it was not long before any possibility of a Cohan on-stage reunion was forever denied due to the sudden death of Josie from heart failure in 1916 and the death of Jerry about a year later from the same cause. George took these two losses very hard, famously collapsing at Josie’s funeral. But Nellie lived for another 11 years, a rock for George to lean on, until her death in 1928.

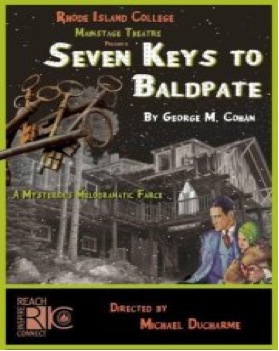

The two greatest achievements of George’s career occurred during this second decade of the 20th century. He adapted Earl Derr Biggers’ humorous mystery novel, Seven Keys to Baldpate for the stage in 1913, creating perhaps the best, and certainly the most enduring of all his stage works, and he wrote the words and music for the song “Over There,” inspired by the United State’s declaration of war against Germany and her allies in 1917. Written by George as a single tune not connected to any of his musicals, this song, became the marching song for the American Expeditionary Force that fought in France and helped to end World War I. Baldpate was first performed with Wallace Eddinger in the lead role of Magee, a writer trying to win a bet that he could compose a novel in 24 hours, holed up in what he thinks will be a closed-for-the-winter summer resort to get the piece and quiet he needs to write. In later touring versions George himself would play the lead to much audience acclaim.

“Over There” is worth mentioning both for its effect on American society, focusing as it does on this new idea of America somehow fixing the big mess in the Old World of Europe, and for its musical construction. After an introductory verse, the chorus consists of repetitions of a three-note, bugle call-like melody, but unlike other Cohan tunes of this time the theme is not a direct quote. This three-note, mi-sol-do pattern may be original with Cohan. Certainly it is not to be found in the three most recognizable U.S. service calls – Reveille (the wake-up call), Taps (the lights out or memorial call), and Mess Call (the signal for food to be served – also known as the call that starts a horse race).

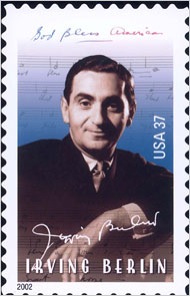

The song also features two judiciously placed bits of syncopation (“the Yanks are coming, the Yanks are coming”) that inject a bit of fun into what otherwise is a basic march. It also references the syncopations of ragtime – a vigorous American music for a vigorous American culture. There are also playful word sound effects using common colloquialisms (“And we won’t come back till it’s over Over There”) that make this the one of the most lightheartedly patriotic war song ever written. It was also a great recruiting tool for the Armed Forces, it boosted the morale of the troops on the battlefield and of the people back home – and it made George a fortune. It is interesting to note that the great long-lived American songwriter, Irving Berlin wrote his first big hit (and as many would acclaim, the first big ragtime hit), “Alexander’s Ragtime Band,” very much in the Cohan style – and very much like “Over There” in particular.

Berlin was a protégé of George’s and actually was hired by George to write songs for one of his vaudeville review shows during this period. Berlin’s song uses the same “Over There” bugle call (in a slightly different rhythm) and also features an inserted melody with its reference to Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home” (also known as “Way Down Upon the Swanee River”) just before the end of the chorus (“If you want to hear that Swanee River played in ragtime”). But Berlin inserted the Foster tune in such a way that it sneaks by the listener due to a greatly altered rhythm (though the pitch sequence of Foster’s melody is still intact) and by shifting the words “Swanee River “ to a place just before Foster’s melody would have them, where Berlin has the words “played in ragtime.”

This was quite a sophisticated piece of writing – the type of song craft George, who wrote very quickly, would not have spent much time trying to achieve, even if he thought that such subtleties were worth the trouble – which he usually didn’t. It was this advanced musical approach by a younger generation of composers that would over the next decades gain acceptance with performers, and by extension with the public. As the years progressed George’s music was appreciated more as an emblem of star-spangled nostalgia – heard mostly at public school patriotic assemblies and Fourth of July parades – than as part of any current popular music scene. This troubled George during the last part of his career.

Equity and After

By the summer of 1919, however, the partnership of Cohan and Harris had been going full steam. Since the spring of the previous year they produced nine plays, three written by George himself, including The Royal Vagabond, a hit musical that parodied European operettas. All this activity showed that George and Sam were among the hardest working showmen on Broadway, and it also pointed out how much the people who worked for George and Sam contributed to that success. In general the actors and stagehands were willing to work the extra hours needed to fix or change things in a production because the Cohan and Harris team worked right along beside them. Plus, Cohan and Harris were known to be more than fair with all their employees, compensating them for all rehearsals and providing for all costumes, both of which were not standard practice in those days. In fact, actors had to bring or pay for their own costumes, and it was not uncommon for an actor to rehearse a play for no pay only to be substituted by a bigger star just as the show was about to make money.

These and other grievances were the reason The Actors’ Equity Association was created. The union had been slowly building membership for several years and by the summer of 1919 it was ready to demand recognition from the Producing Managers Association as the sole representatives of all working actors in professional theater. They demanded changes in the lengths of rehearsals, payment schemes, actor’s safety, job security within contractual agreements, and other items that theater managers were reluctant to make. Cohan and Harris, being independent producers, were already among the more progressive employers on Broadway, however when the union called for a strike and actors started walking out of productions, including George’s still running The Royal Vagabond, George hit the roof. He came back from the start of a much-needed vacation to rescue his play, promoting chorus members to leading roles and he and some of his associates taking on roles as well. Eventually the stagehands and musicians struck in sympathy and the show had to close along with every other professional show, both in New York and Chicago.

A fundraising adaptation of Marc Antony's funeral oration given during the 1919 actors' strike - recreated for this photograph.

This continued for about a month until the theater owners realized how much revenue they were losing, and little by little they gave in to union demands. Surprisingly, George was the most vocal of all the theater owners in opposition to Equity. He even helped to create an opposing organization called the Actors’ Fidelity League (derisively called “Fidos” by striking actors) made up of mostly big-name stars that had the least amount of grievances and the most salary to lose with shows being closed. So what was the cause of this aggressive front from someone who came up through the ranks as a song and dance man and was now among the great comedic actors of his generation?

The answer is that by this time George mostly thought of himself as a theater manager and as a creator of entertainment, writing and directing plays, and composing songs. Also, he inherited his father’s philosophy that acting was a profession, that actors owed it to the public to help provide what little escape they might get from their work-a-day world, much as a doctor or nurse owed it to the public to provide relief and protection from diseases and misfortune. For actors to intentionally close a show was anathema to George, and for a union to step in and tell him whom he could or could not hire also went against every grain in his body. He felt like Peck’s Bad Boy again, surrounded by kids in the back alley threatening to beat him up. And there was a certain amount of actual violence during this strike, some of which was pointed at George and his family – shots were supposedly fired at his family compound at Great Neck, Long Island while his family was there. George never forgot or forgave Equity for that.

Francis Wilson, first president of Actors' Equity Association and George's opponent during the 1919 strike.

By September the strike was settled and gradually most of the changes the union demanded were put into effect. But the partnership of George M. Cohan and Samuel H. Harris didn’t survive much past the Equity strike. Sam could see some benefit to having Broadway as a union shop – there were, for example, guarantees in place for actors honoring their contracts, preventing them from quitting a show to take on a better paying role somewhere else. George could never accept Sam’s view of things, so they amicably parted ways (however, they remained personal friends – as well as in-laws – for the rest of their lives).

In truth, Sam was starting to have creative differences with George, seeing much of worth in the new realism of the younger writers while George generally preferred sugarcoated escapism. Sam went on to become one of the greatest producers in Broadway, with important shows to his credit including Of Thee I Sing! (with music by George Gershwin), George S. Kaufman’s You Can’t Take It With You, and a stage version of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice And Men. George’s productions were nowhere near as important in the eyes of the critics or as successful with the younger audience.

The Colossus Stands Alone

For the next twenty years or so George would sporadically announce his retirement, only to return again when the call of the spotlight beckoned and some project captured his enthusiastic attention. He would take vacation trips with Agnes to Europe, frequently taking in theatre shows in London and Paris and ironically, given his dispute with Actor’s Equity, getting inspired to devote serious attention to his acting skills after observing the methods of actors overseas. He took time to write his autobiography Twenty Years on Broadway and the Years It Took to Get There, and in 1920 he created one more work of lasting quality with The Tavern, a strange send-up of mystery plays that George adapted from a proto-feminist potboiler by first-time playwright Cora Dick Gantt. For The Tavern George took Gantt’s mysterious stranger protagonist and made him an over-the-top romantic lead as in The Royal Vagabond and placed him in a remote setting on a dark and stormy night with various comings and goings like Seven Keys to Baldpate – but with a twist at the end. This non-musical production drew decent audiences and ran for over 250 performances at the Cohan Theatre, and the lead role of “The Vagabond” was one of George’s favorites. In a 1930s revival of The Tavern, Mary Cohan, the only one of George’s children to seriously study music, added an incidental orchestral score.

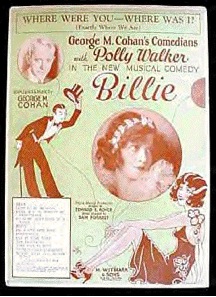

There were thirty-one more plays produced for Broadway during the latter part of George’s career, both musical and non-musical, the slight majority of which were Cohan originals, the rest being for the most part extensive re-writes of other people’s work. Most of these productions were directed by George (or executively directed by him) and featured George as the lead actor. These plays were typically tried out in either Philadelphia, or Atlantic City, where George spent much of his time. The best of George’s original works during this period include the inverted autobiography The Song and Dance Man (1923) – in which a veteran performer, not unlike George himself, makes a series of bad choices and ends up as a bum on the street, The Merry Malones (1927), Billie (1928) – his last original musical, and the metaphysical Pigeons and People (1932).

A song from Billie a musical version of the earlier Broadway Jones, lead actress Polly Walker is pictured.

It should be noted that even shows that tanked in New York would make money on the road, plus George’s original plays were in demand by companies across the country and George would make money on the licensing of performance rights through the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) of which George was a founding member in 1915. And by this point George was a music publisher as well as a composer and author so he made money on the sale of sheet music. As George himself declared during a lawsuit against him, “I’ve never lost money on anything I’ve done.” It was no wonder then that he came under the microscope of the Federal tax authorities and he was audited in 1930. It seems George had claimed business travel and entertainment deductions for which he had no documentation. George’s lawyers argued that a man as busy as George was couldn’t possibly keep track of every little expense, and since it was obvious that the expenses were incurred (as they are for every theatrical producer) and therefore a reasonable estimate should be allowed. The judge in the case agreed with George and the Cohan Rule was born. But be careful, kid, if you use the Cohan Rule in an audit you’ll have to show that your estimated expenses are real and legitimate – and expect the IRS to not give you the full amount of deductions you’re hoping to get. So it’s still a good idea to document everything if you can.

Ah, Wilderness!

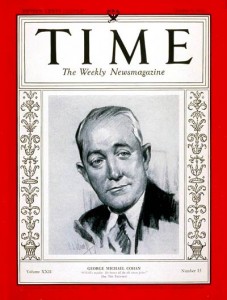

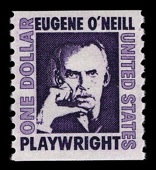

After Pigeons and People it was time for something new, and for first time since his teenage years the famous playwright and composer, George M. Cohan, spoke lines on stage that he himself did not write (or re-write) when he took on the role of the father in Eugene O’Neill’s comedy Ah, Wilderness! This show, under the direction of Philip Moeller for the Theatre Guild of New York, opened to great acclaim in October of 1933 and ran for 232 performances. Everything came together quite naturally for George, in spite of his initial trepidation and the end result was a career upswing, earning him praises as “America’s First Actor” and placed his picture on the cover of Time magazine.

George had a natural affinity for O’Neill, who was Irish-American like himself, and who was also the son of a vaudeville trouper – James O’Neill. In addition, the character of the gentle but firm father, a newspaper editor from around the turn of the 20th century, appealed to George and he developed many subtle insights into the role. After Ah, Wilderness! closed in New York; George spent the next few years with the play on the road as part of a national touring company. However even with all the accolades, George would still occasionally grouse about not being in a play of his own creation, as Bennett Cerf relates in his 1950 book of humorous anecdotes, “Shake Before Using.” Cerf tells of an exchange between Cohan and an admirer in which George responds, “Imagine me reciting lines by O’Neill! O’Neill should be on stage reciting lines by me.”

Throughout his career, George spent almost all of his performance time in the living, breathing theater in front of live audiences – but he did from time to time act in front of a camera. In 1915 he filmed three moving picture adaptations of his plays, including one for Seven Keys to Baldpate. They were mostly shot in New York, and they were completed in a little over two months time. In 1932 he went to Hollywood to play a dual role of a Presidential candidate and his medicine show, snake oil selling doppelganger in a musical film called The Phantom President, co-starring Claudette Colbert and Jimmy Durante. It featured songs by Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart and it remains the only example in recorded sound and image of George M. Cohan singing and dancing.

The film was not a happy experience for George – the producers did not accept any of his re-writes of the script, nor did they use any of his music and it played to only lukewarm houses. But he gave movie acting one more try, this time on his own turf, when in 1934 during a break in Ah, Wilderness! he filmed a version of his 1929 stage play Gambling. That summer betting on sports events was much in the news and when approached to do a movie, George thought his play might connect with an audience. He spent two weeks of filming on Long Island, but after the movie opened it promptly disappeared without a trace. It is now thought to be a lost film.

I’d Rather Be Right

Now as you probably know, kid, the 1930s were the Depression years. A time when capitalism took a mighty downward swing, leaving people sprawling left and right, without jobs, and in many cases without any savings to tide them over. Perhaps the hardest hit of all Americans affected were the World War I veterans. The ones who marched off to the fight singing George M. Cohan tunes, believing they were making a better world. Now there were new sadder songs to sing, like “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” by Yip Harburg and Jay Gorney, a 1931 song sung from the perspective of a railroad worker, a construction worker, and lastly, from the bridge section through to the end of the chorus, an unemployed veteran, who reminisces about the war years while pointing a finger at George’s brand of naïve patriotism:

Once in khaki suits – Gee, we looked swell!

Full of that Yankee Doodly Dum.

A half a million boots went marching through Hell,

And I was the kid with the drum!

And yet there was much good feeling for the man himself, many of George’s plays still drew a decent enough audience, especially on the road, or as performed by regional theatres in places far from the Great White Way. He still represented something vibrant, dependably entertaining and distinctly American, his talent lighting up the darkness at home and shining in the face of threats from abroad. Brown University thought so, offering him an honorary degree in 1935 (which George declined), and certainly the U.S. Congress thought so, awarding him the Congressional Gold Medal (the civilian equivalent of the Medal of Honor for military valor) in 1936 in recognition of the morale-boosting powers of “Over There” and his other patriotic tunes. This was the first time this award was given for artistic achievement. The award was to be presented to him by then President Franklin D. Roosevelt, but George put off receiving it from him for four years – probably in the hopes that he could receive it from a new president, since he didn’t like Roosevelt’s pro-union stance. He finally did accept the award from Roosevelt in 1940.

As much as he disliked President Roosevelt’s policies, George was willing to play the President in the 1937 musical comedy I’d Rather be Right, written by George S. Kaufman and Moss Hart and featured songs by Rodgers and Hart, the songwriting team that worked with George in the movie The Phantom President. George’s old partner and brother-in-law, Sam Harris, produced this political farce after he and George revived their partnership earlier in the year for one more play – George’s own Fulton of Oak Falls, which had a brief run in the early months of same year.

I’d Rather be Right concerns a young couple that can’t get married unless President Roosevelt balances the federal budget! Despite the improbable premise, and a mediocre score from Rodgers and Hart, the show was a great success, largely due to George’s star performance as a song-and-dance-man President. Those theater-loving New Yorkers who had pretty much written George off as being hopelessly old fashioned suddenly appreciated his talent in this unusual setting. I’d Rather Be Right was George’s late career comeback. After the Broadway run, the show went on the road for the next two years with George as the lead attraction, eventually ending in Providence for the final show of the tour in February 1939.

The Final Act

As much as he enjoyed the limelight, and as much as he enjoyed being active in the theatre, George felt a man out sync with the times while doing I’d Rather Be Right. The melodies of Rodgers and Hart (who George only half-jokingly referred to as “Gilbert and Sullivan”) were not the type George would normally write for himself to sing – too many chords, too many notes. But pro that he was, he put his all into the performance even as this “modern” music made him realize that his time had passed. Perhaps by this time George was starting to feel the effects of sixty years on stage, perhaps he was beginning to feel the onset of the intestinal cancer that would eventually kill him, in any case he started to slow down. Yet he wasn’t going to go quietly – using the public appeal he generated from I’d Rather Be Right, he wanted to create a new vehicle for the “Vagabond” from his 1920 play The Tavern. This man of mystery who may or may not be insane was by George’s own estimation the favorite of all his creations and he created The Return of the Vagabond to inhabit that world again – a world from a time when he was still the King of Broadway. In May of 1940 he took the production to Providence and Boston for out of town tryouts, getting good reviews and decent houses. But the show died on Broadway, lasting for only seven performances.

George’s disappointment however was soon to be lifted. In 1939 just as George was finishing his time with the F.D.R. musical, Walter Kerr at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C put together a low budget college production of George’s music. The approach was something new, in that the music was used to tell the up and down story of George’s actual career in the theater. Up to this time, the usual procedure for composer retrospectives was to create a fictional love story, a clothesline off of which the songs were hung. This chronologically organized review, called The Yankee Doodle Boy, had George’s blessing and he even went down to Washington to advise the actors during rehearsals and attend the performances. He was reputedly pleased with the result. A year later in 1940, the year of The Return of the Vagabond’s short run, Kerr sold the rights to his Cohan musical to Warner Brothers for a movie project that would eventually feature James Cagney, a one time vaudevillian who was known for playing gangsters in movies during the 1930s.

The studio got George’s permission to make the film with the stipulation that none of his personal life would be included. The studio agreed, and the screenwriters created a fictional composite of Ethel and Agnes for George’s wife, which, not surprisingly, was the main sticking point from George’s perspective. The movie, re-titled Yankee Doodle Dandy, went into production in 1941 for a 1942 release – and thanks to Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor in December of 1941 and the onset of World War II – George’s style of razzle-dazzle patriotism was suddenly in vogue again and the movie was a big hit, earning Cagney an Academy Award for best actor in 1943. By all accounts George, with some reservations, liked what he saw in previews and he really like Cagney’s portrayal, exclaiming to his son, George M., Jr., “My God, what an act to follow!”

By 1941 George knew he had cancer, and he underwent a series of operations to try to arrest the disease. In recuperation he put the finishing touches on one more musical titled appropriately enough The Musical Comedy Man, a show within a show for which he would once again play the lead. Unfortunately his health deteriorated and it never got off the ground. Many of the books and articles about George mention the bittersweet scene of his going out from his sickbed for one last time to visit Broadway during the summer of 1942, including a brief visit to a movie theater playing Yankee Doodle Dandy.

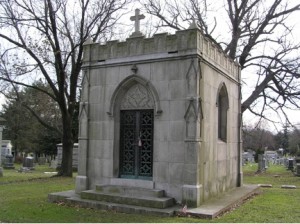

But such feistiness could not last and by November, George had slipped into a coma and early in the morning of November 5th George M. Cohan, the kid from Fox Point and the colossal King of Broadway passed away. He was buried in the family mausoleum beside his mother, father and sister (and joined much later by his wife, Agnes) at Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx after a Requiem Mass at St. Patrick’s Cathedral and a funeral procession witnessed by thousands.

George’s life was very much in the here and now, he was not known to be especially religious (though he was president of the Catholic Actor’s Guild in his later years). The song “Life’s a Funny Proposition After All” from Little Johnny Jones perhaps best describes George’s feelings about the mystery of existence, and incidentally George’s recording of it (which you can hear online from the Library of Congress web site, the link for which we’ve posted below) was used during the final scene in the first season finale of the very existential HBO Prohibition era drama Boardwalk Empire. Its lines sung-spoken by George with a sense of bemused detachment:

Hurried and worried

Until we’re buried

And there’s no curtain call

Life’s a funny proposition after all.

Miscellany

COHAN MEMORIALS

Rhode Islanders honored their native son while he was still alive in August of 1942 with a modest plaque marking the address of his birth accompanied by an afternoon program celebrating George’s life and work. It was the first public memorial dedicated to George. New York honored George with a large statue erected in 1959 in the heart of the NYC theater district at Times Square; it is the only public monument to an actor anywhere on Broadway. It is interesting to note that during the fundraising for the Times Square statue, Oscar Hammerstein II, as head of the committee, complained bitterly about the measly contribution from Actor’s Equity. Apparently the old antagonism from the days of the strike and the years that followed was still lingering in the memory of some of its members.

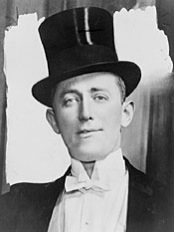

Providence again honored George by re-naming Fox Point Boulevard, a 1930 service road that today runs along I-195, the George M. Cohan Blvd. Then in 2009, a more significant Fox Point memorial was unveiled – a bust of George with top hat in hand and arm outstretched in mid-song that was erected in the newly named George M. Cohan Plaza, where Governor and Wickenden streets meet. Sy and Judi Dill, a New York couple who retired here in Providence some years ago were appalled that there was only the plaque to honor arguably the greatest Rhode Islander after Nathaniel Greene (who was, in case you don’t know, George Washington’s second-in-command during the Revolutionary War). They spearheaded a committee to build a proper memorial in the city for George M. and settled on the recently renovated Governor and Wickenden intersection in Fox Point, as chance would have it not too far from his birthplace making it the perfect location. After getting city approval, they commissioned sculptor Robert Shure, who had just completed the Irish Famine Memorial along the Providence River, to create a livelier statue than the one in Times Square. Shure was willing to work on the speculation of getting paid later, toward which end the Dills have been promoting fundraising events like the annual presentation of the George M. Cohan Award for Excellence in Art & Culture. They are also fundraising toward the promotion of other Cohan related activities in the future.

.

Meanwhile on the other side of the country, there’s one more memorial worth mentioning, a surprising one given George’s antipathy to Hollywood, he has his own star in the Walk of Fame at 6734 Hollywood Boulevard. But of course the greatest Cohan monument is the vibrant and flourishing state of American musical theater. Yet we wonder what George would say about the typical cost of a Broadway ticket today since he always believed in giving people good entertainment at reasonable prices. All things considered he’d probably be happy with the price of touring show tickets, like those that play at the downtown Providence Performing Arts Center – incidentally, PPAC will be launching three such national touring shows for the 2013-2014 season.

GEORGE AND RHODE ISLAND

Much is made of George’s dislike of Rhode Island in general and Providence in particular. And vice versa, the line around here is that yeah, he was born here, but he wasn’t from here. Yet that may be the point, since George wasn’t really from anywhere. He was basically raised out of a suitcase as the Four Cohans traveled the country like wandering minstrels. So Providence was an anchor to the self described “little old kid from Rhode Island.”

North Brookfield, MA, the only place other than Rhode Island in which he spent any extended amount of time as a young man, was more like a vacation retreat than a second home (even with Jerry Cohan’s mother living nearby). Most of Nellie Cohan’s relatives lived in Providence, and some of Jerry’s as well. George’s earliest memories of any kind of stability would have been living with aunts and uncles, playing on Governor Street and, as disagreeable as it was, going to public school in and around Fox Point. That is why it stung so much whenever he got a bad review or lukewarm turn out when he played Rhode Island – contributing to a love/hate relationship that seemed to ease in intensity, as he grew older.

We think it psychologically meaningful that George played one of his greatest roles in Providence, as F.D.R. in I’d Rather Be Right for the final show of its extended nationwide tour, and that he shortly thereafter chose to open The Return of the Vagabond, his ultimate presentation, here in the RI capital as well. It was as if he was coming home.

GEORGE’S LACK OF FORMAL SCHOOLING

You may ask yourself, how could someone who spent so little time in school become one of the richest men in show business? The answer must lie with his parents who involved their children in every aspect of their daily lives, Jerry going so far as to entrust the family’s career to care of his talented, but hot-tempered, teen-aged son – and George being a quick learner was soon booking shows, scheduling tours, and negotiating fees for the family business. The Cohan children could read, write and do practical math as well as, if not better than many a school-educated child. They were in essence home schooled (without any particular home involved), Jerry, Nellie, fellow performers, friends, relatives and even other children all pitching in. For example, one of young George’s North Brookfield buddies, Dennis “Cap” O’Brien, is credited with helping George with his spelling and grammar during those summer evening song and sketch writing sessions. George would later repay O’Brien by giving him money for law school, and “Cap” would eventually become a successful showbiz lawyer in New York, with George as one of his clients.

John Dewey, the eminent educational philosopher, proposed “learning by doing” as the only true method to teach, and an extension of that idea, mooted by some modern theorists, is that many children just aren’t ready to sit still in formal classrooms, attempting to retain abstract information, until they reach high school age. Instead they should go out and do what kids do – play games, sing and dance, build things – take things apart, and explore their world with enough adult supervision to keep them focused, plugging in enough of the reading, writing and math skills as they can handle in accomplishing their tasks. George M. Cohan would be the poster boy for that approach.

However, George didn’t want that kind of experience for his own children. Agnes, George’s second wife, was a stay at home mom and the kids went to school. This provided a stable lifestyle that perhaps George may have wanted for himself. And though a loving and attentive father, George was never as involved in the schooling of his children as his parents were with him and Josie. In fact for high school George enrolled Helen and Mary (his two daughters with Agnes) in an exclusive Catholic boarding school just outside of Paris. While teenaged George was hardly ever further than the next hotel room from his parents.

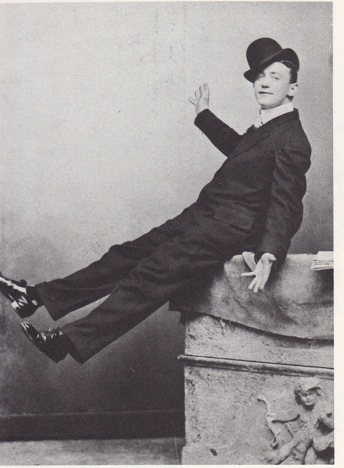

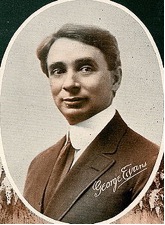

COHAN AND THE COON SONG

If you Google “George M. Cohan” the first link that comes up, as it does for most searches, is for the Wikipedia site. The Cohan article in Wikipedia has among its content the decorative cover for the sheet music of “The Gibson Coon,” a song written for the 1909 Cohan and Harris Minstrels. George and Sam’s heads are shown in sideways profile on the cover, illustrating their partnership, which I assume is the reason for its inclusion in the Wikipedia entry. But the main image on the cover is that of a grinning African American man in an outlandish circus band uniform, an offensive image to most people today. It is most likely a portrayal of the show’s star, George “Honey Boy” Evans, a white Welsh-born black-faced comedian who co-wrote the show with Cohan. As wrong as that image is, it is at least recognizably human, most of the other coon songs of this period had covers that were far more grotesque and demeaning, such as the cover for George’s early ragtime song, “The Warmest Baby in the Bunch.”

Musically the coon song was simplified ragtime, with a catchy vocal refrain, usually the title of the song. Directly or indirectly the lyrics to these songs take the 19th century minstrel character Zip Coon, the sharp-dressing freed slave who’s too smart for his own good, and places him in an urban setting, as in George’s “I Guess I’ll Have to Telegraph My Baby.” Sometimes the lyrics were written in Afro-American dialect, other times not, though they were probably all performed in dialect to some degree or another. The coon song faded in popularity after World War I, though traces of its humorous and/or stereotypical characterizations of African American culture can be detected in some contemporary styles of music, and in the routines of stand-up comedians, both white and black.

We’re not sure what the subject of “The Gibson Coon” is, but the title sounds like a parody of the Gibson Girl, a type of perfect Caucasian female depicted in illustrations by American artist Charles Dana Gibson from the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The 1909 minstrel show that featured the song was the only black-faced show that Cohan produced and it only ran for sixteen performances in New York, though it seems likely that “Honey Boy” Evans and his 100 Honey Boys would have taken the show out on tour, which probably accounts for the publication of the sheet music.

George "Honey Boy" Evans, blackface minstrel performer and songwriter whose best-known song is "In The Good Old Summertime."

George didn’t feature any African-American characters in his own works, but he did feature Chinese-Americans as criminal gamblers in Little Johnny Jones, with a subplot that takes Ethel Levey’s character from London to San Francisco’s Chinatown where George rescues her from her kidnappers. As you can imagine this provided plenty of opportunity racist ethnic humor. But I don’t think George had anything against Asian Americans in particular, in fact he had a Japanese-American personal assistant for most of his later years. We think this strange left turn of a plot twist was more of an inside joke between George and Ethel, who was from San Francisco, and who probably enjoyed the opportunity to poke a little fun at her home town.

George was probably no more or less racist than most white Americans of that time. But John McCabe in his Cohan biography mentions that among the performers at the banquet for George’s 1910 induction to the Friar’s Club, a Manhattan social organization for actors to which his father belonged, was Bert Williams, the great African-American vaudevillian, known for his song “Nobody.” McCabe states that Williams’ performance of his signature song was one of the highlights of the evening. This may show that George appreciated Williams’ talent, but not enough unfortunately to overcome the conventions of the day and cast Williams, or any other talented actor of color into one of his shows.

It’s ironic that a good portion of the only extant audio/visual recording of George singing and dancing has him in blackface. The Phantom President, the Hollywood musical that had George playing a double role, one of which was as a huckster in a two-man medicine show, who in order to fool an audience into thinking there were more than two people involved in his troupe first performed a minstrel show type routine, then after a quick change of costume came out and did another dance this time without the black greasepaint. Unlike Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor, two Jewish American actor/singers of the same period, George M. Cohan never performed in blackface for his own shows.

If we had to compare George to a modern entertainer, I’d choose the supremely talented and creative African-American singer, dancer and songwriter Michael Jackson. They both were child performers in a family group. They both took control of their own destinies, handling their own artistic development and business dealings. They both were pioneers in combining music and drama – Cohan with the story derived musical play and Jackson with the long form music video. They both were involved in music publishing (Michael famously purchasing the rights to Northern Songs, the Lennon-McCartney Beatles catalog). Their career trajectories took a similar shape with their greatest accomplishments achieved while still fairly young followed by a long trailing off. Yet they both were very successful financially, and they both had a certain degree of difficulty in their personal relationships. And the effects of both men on American culture can still be felt even at this present time, though George’s is perhaps not as immediately noticed – something the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame has addressed by including George among this years inductees.

James Cagney recreating George's signature run up the proscenium; Michael Jackson's signature moonwalk.

Another connection to contemporary African-American culture could be made through George’s tendency to use recognizable non-original melodies and words in his original songs. The same aesthetic in hip hop (the overall term for urban black culture in the United States since the late 1970s) that has disc jockeys manipulating phonographic records to provide backing for rappers in live performance and record producers digitally sampling recordings to create the catchy hooks for modern pop music of all kinds, can be found in “The Yankee Doodle Boy” and “You’re a Grand Old Flag.” They all create something new by incorporating, with modifications, something recognizably old (or recognizably non-original).

GEORGE’S THEATRICAL LEGACY

Not many theater companies have attempted to revive George’s musicals, they may be too much of their own day to succeed in our time without extensive re-writing (the kind of thing George did to other people’s plays when he produced them) and of course you might have to have a George M. Cohan on board to pull them off. A case in point, there was an early 80s touring show of Little Johnny Jones that stared David Cassidy of The Partridge Family TV show (which was inspired by the real family band, The Cowsills, also from Rhode Island and also inducted into the RI Music Hall of Fame along with George M. Cohan). However when Donny Osmond took over the lead in time for its Broadway opening, the show closed after one performance.

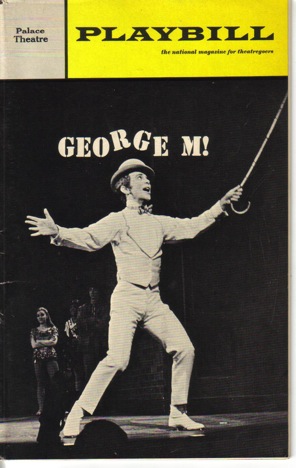

Yet George’s music in review has fared well on the stage, George M. Cohan, Tonight! a 2006 one-man dramatic review by Chip Deffaa has been playing regularly off Broadway – Deffaa, a well-respected jazz historian, has built several plays of varying cast sizes around George’s music. But the last big, Yankee Doodle Dandy styled Cohanic experience on the Great White Way was George M! A more accurate telling of George’s life story than the 1942 movie was, it featured songs and lyrics adapted for the stage by George’s daughter Mary Cohan Ronkin. The show opened in 1968, making stars out of lead actors Joel Grey and Bernadette Peters, who portrayed Josephine Cohan. While this high-energy show hasn’t been on Broadway since it closed after a year long run in 1969, it is frequently in production by local and regional theater companies. In this area, Theatre By The Sea gave a summer stock rendition of George M! as recently as 2008.

It’s been much longer since Trinity Rep, the leading professional company in Rhode Island, has done any Cohan. It did Seven Keys to Baldpate (1976-77 season) under the direction of founder Adrian Hall and The Tavern (1985-86 season) directed by Tony Giordano. But now local theatergoers will for the first time in over 20 years get the chance to see a top level production of Seven Keys to Baldpate when the well respected Rhode Island College Department of Music, Theatre and Dance presents the mystery as part of its Spring 2013 season under the direction of Michael Ducharme. This fortuitous bit of programming is coincidentally tied to George M.’s induction into the RI Music Hall of Fame on April 28th. And as George certainly understood so well, good timing is everything!

Resources and Reference

LISTENING AND VIEWING

1. The George M. Cohan portion in the first part of the six-part 2012 PBS documentary about Broadway, including archival footage of George dancing on stage in I’d Rather Be Right.

2. Excerpts from a 2005 Irish production of Dion Boucicault’s The Colleen Bawn. Boucicault’s work was an important influence on the young Cohan and this YouTube video gives a good sampling of his dramatic and musical style…if you can ignore the musical underscore that runs throughout.

3. Library of Congress pages showing George M. Cohan related recordings, including sound files for the five studio recordings George made in 1911. Also featured are several recordings of Cohan songs, some as early as 1903, several performed by Billy Murray, who sounds just like Cohan.

4. Library of Congress page for Irving Berlin’s “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” in a 1911 theatrical-sounding rendition by Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan (aka Collins and Harlan). The duo specialized in “coon songs” (they also satirized the Irish and farmers) and there’s a bit of that flavor in this recording. We suspect that the higher voiced singer was probably dressed as a woman when they performed this on sage.

5. Ethel Levey singing “My Tango Girl” from a 1913 London production Hello Tango! Illustrated by several pictures of Ethel in posed stage portraits.

6. Bert Williams 1913 recording of his comic masterpiece “Nobody.” The trombone obbligato adds to the deadpan humor.

7. The complete 1917 silent film of George in “Seven Keys to Baldpate” from the Internet Archive website.

8. Library of Congress page of the original hit version of “Over There” sung by Nora Bayes.

9. Library of Congress page of Italian Opera star Enrico Caruso’s 1918 bilingual (English and French) version of “Over There,” making this quintessentially American song sound like something out of the Follies Begères.

10. A 1919 Edison wax cylinder recording of an instrumental medley from The Royal Vagabond, the show affected by the Equity strike.

11. A 1930s recording of “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” sung by Al Jolson – The anti-“Over There.”

12. George singing and dancing in The Phantom President (1932), the only example in both sound and moving image.

PRINT RESOURCES

Louis Botto, At This Theatre, edited by Robert Viagas (New York: Applause Theatre & cinema Books, 2002).

Bennett Cerf, Shake Well Before Using (Garden City, NY: Garden City Books, 1950).

George M. Cohan, Twenty Years on Broadway and the Years It Took to Get There (New York: Harper Brothers, 1925; reprint, Westport, CT: Greenwood, 1953).

Carolyn Livingston, “George M. Cohan: Rhode Island’s Yankee Doodle Dandy” in Rhode Island’s Musical Heritage: An Exploration, edited by Carolyn Livingston and Dawn Elizabeth Smith (Sterling Heights, MI: Harmonie Park Press, 2008).

John McCabe, George M. Cohan: The Man Who Owned Broadway (Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Doubleday, 1973).

Ward Morehouse, George M. Cohan Prince of the American Theatre (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippencott, 1943).

ONLINE ARTICLES

“1919: Why Should the Actor Hesitate?” Equity Timeline, Actors’ Equity site

http://www.actorsequity.org/aboutequity/timeline/timeline_1919.html

Sam Alder-Bell, “Hey Providence, what is that?” The College Hill Independent site (2011)

http://students.brown.edu/College_Hill_Independent/?p=5497

(Article about Cohan and Sy Dill, the Providence man who raised funds for the Wickenden St. Cohan memorial)

“C. Grahame-White Weds – Flight Commander Maries Ethel Levey” (12/22/16), New York Times site (2013)

http://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F50F1EFC39591A7A93C0AB1789D95F428185F9

(Webpage provides a link for a pdf download of the article)

Elizabeth Titrington Craft, “Musical of the Month: Little Johnny Jones,” New York Public Library site (2012)

http://www.nypl.org/blog/2012/07/21/musical-month-little-johnny-jones

Fred W. Daily, “Getting Audited? Can’t Find All Of Your Records? No Problem” (1997), Uncle Fed’s Tax Board site (2009)

http://www.unclefed.com/AuthorsRow/Daily/fwdgetaudited.html

“George M. Cohan,” Wikipedia site (1913)

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/George_M._Cohan

“George M. Cohan, 64, Dies at Home Here,” New York Times (11/6/42)

http://www.nytimes.com/learning/general/onthisday/bday/0703.html

John Kenrick, “The George M. Cohan Revue: Danny’s Skylight Room – NYC

Summer 2004,” Musicals 101 site (2004) http://www.musicals101.com/cohanrevue.htm

(A review of one of Chip Deffaa’s Cohan plays for small ensemble.)

Ken Liss, “She Was His ‘Yankee Doodle Gal’,” Muddy River Musings site (2009)

http://brooklinehistory.blogspot.com/2009/07/she-was-his-yankee-doodle-gal.html

(Article about Agnes Nolan on site dedicated to Brookline, MA history)

Peter Papas, “The Cohan Rule: Can a Taxpayer Estimate His Taxes?” The Tax Lawyer’s Blog site (2008)

http://www.pappasontaxes.com/index.php/2008/08/06/can-a-taxpayer-estimate-his-deductible-expenses/

Richard A. Reublin and Richard G. Beil, “The Music of George M. Cohan, ” The Parlor Songs Academy site (2013)

http://parlorsongs.com/bios/cohan/cohan.php

Randy Rice, “Review: ‘George M!’ at Theatre by the Sea,” Broadway World – Boston site (2008)

http://boston.broadwayworld.com/article/Review-George-M-at-Theatre-By-The-Sea-20080621

Sidney Skolsky, “Times Square Tintypes: George M. Cohan” (1932), Cladrite Radio site (2013)

http://www.cladriteradio.com/archives/5115

(This excerpt from Skolsky’s 1932 book outlines George’s history and accomplishments, but it also insinuates that he could be racist and anti-Semitic.)

“Stars of Vaudeville: Ethel Levey,” Travalanche site (2010)

http://travsd.wordpress.com/2010/11/22/stars-of-vaudeville-261-ethel-levey/

(A somewhat negative article towards George in its description of the Cohan/Levey marriage.)

ONLINE RESOURCES

Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project homepage, Department of Special Collections, Donald C. Davidson Library, University of California, Santa Barbara site http://cylinders.library.ucsb.edu/index.php

Fox Point Oral History Project, Fickr site

http://www.flickr.com/groups/foxpointoralhistoryproject/

George M. Cohan and the American Theater site

http://davecol8.tripod.com/index.htm