Julia Ward Howe

THE BATTLE HYMN PACIFIST

AND

RHODE ISLAND’S CITY BY THE SEA

by Gerard H. Heroux

It may surprise my fellow Rhode Islanders to learn that there is a strong local connection to the best-known, most beloved song ever to have originated from these United States. A song that until recently was for many years our country’s de facto national hymn. A song whose words have been an inspiration to many during times of great struggle and national distress, and a song particularly associated with the American civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s. The Battle Hymn of the Republic (best recognized from its stirring refrain “Glory, Glory Hallelujah!”) is that famous song, and its author, Julia Ward Howe (1819 -1910) was a nearly life-long summer resident on Aquidneck Island, first in Newport as a teenager, and later at two different country homes in the southern end of Portsmouth.

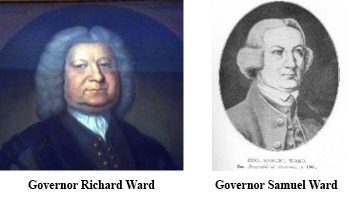

Julia’s Rhode Island ties go deeper than her frequent summer residencies here. On her father’s side, the Wards were among the first English families to settle Aquidneck Island, and in succeeding generations they produced two colonial governors: Richard Ward (1689-1763) and Julia’s great-grandfather, Samuel Ward (1725-1776), who was an RI delegate to the Continental Congress in Philadelphia but died some three months before the July 4th signing of the Declaration of Independence. From her mother’s side of the family some of Julia’s ancestors were among the first out-of-state families to choose Newport as a summer vacation destination, coming up from Charleston, South Carolina beginning in the 1720s. The most famous person from her mother’s family was General Francis Marion, known as the “Swamp Fox” for his exploits in the South conducting a guerilla campaign against the British during the Revolutionary War.

Detail from a painting that hangs in the U.S. Capitol by John Blake White (1781-1859) showing Julia’s great grand-uncle Francis Marion (in blue uniform) offering to share his band’s meager meal of sweet potatoes with a British officer.

Building upon this distinguished heritage, Julia became one of the most famous women of her day – in no small part due to the Battle Hymn lyrics, written in 1861 just after the start of the American Civil War. But she had other achievements as well. In the decade before the war, Julia achieved a measure of success and some public notoriety for her poetry, and for decades after the war she was much in demand as a public speaker. Alongside her husband she worked for the abolition of slavery and on her own she was a champion for causes that flowed out of that effort. She stumped across the U.S. speaking in support of the right to vote for women; she debated the President of Harvard in print over post secondary education for women; and she established international congresses for world peace. She was among the first to promote a Mother’s Day, conceiving it as an international pacifist convention inspired by the ideals of motherhood, and she was a powerful force in the Women’s Club movement, helping to organize chapters around the world.

Not as well known, perhaps, is the fact that Julia Ward Howe was also a classically trained pianist, singer and composer. Among her musical activities: she participated in amateur choruses such as Boston’s Handel and Haydn Society, she taught music to her six children, and she wrote songs. According to the 1915 Pulitzer Prize winning biography written by her daughters, much of what Julia composed was of the nursery rhyme variety meant for the entertainment of her children and grandchildren. An intriguing, fairly recently published (1987) example of Julia’s music for children can be found in Flibberty-Gibbet’s Jig, a story with piano accompaniment credited to Julia Ward Howe via the memory of an unnamed grandson and expanded upon by longtime Newport author Rosalys Hall (1914-2006), who was Julia’s great-great grandniece.

Some of Julia’s songs, however, were composed more for her own personal pleasure, and on occasion she would sing and play these for family and friends. A small collection of these “adult” songs, prosaically entitled Original Poems and Other Verse Set to Music as Songs, was published in the final years of Julia’s life by the Boston Music Company (1908). This collection for medium voice and piano has settings of her own as well as others’ poetry and it exhibits Julia’s straightforward mastery of the popular, European-derived “parlor” music of the early to mid 19th century America – essentially polite music meant for family gatherings around the living room piano in middle and upper class homes.

But unlike the typically sentimental parlor song, Julia’s poetical texts – both her own and those of Goethe, Byron, Wordsworth, and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, among others – reach for something deeper, frequently reflecting on the passing of time and the brevity of life. Yet there are also lighter songs about dancing and singing, and one humorous song written in a backwoods Yankee dialect. The quality of her texts and the richness of her musical conception, nudge her collection a little closer to serious art song. The overall style of the music comes across like Stephen Foster in his Scotch-Irish or Italian ballad style (think “I Dream of Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair” or “Beautiful Dreamer”) combined with the early German romanticism of Franz Schubert and Felix Mendelssohn, exhibiting many changes of musical color, typically through sudden harmonic modulations from major to parallel minor or vice versa.

According to her daughters, Julia was very creative musically during her summer months in Rhode Island, so it’s quite possible that many of the pieces in this now out of print collection were composed and first performed here in the Ocean State, albeit in a non-public, informal setting. The publisher of Original Poems, Boston Music, has been out of business for the past ten years, yet G. Schirmer – a still current entity whose catalog is handled by the American music giant, Hal Leonard Publications – held the original copyright. But since this collection was published before 1925, according to U.S. copyright law, it is now in the public domain. So if you’re interested, I have included an index at the end of this article from which you may freely download and enjoy the pdf files for these songs. I scanned the pages from a copy of Original Poems borrowed from the Providence Public Library (1 of only 15 libraries world-wide listing this title).

Julia’s Life Story in Brief

Julia Ward was born into a wealthy New York family, the fourth of seven children and the eldest surviving daughter. Julia and her siblings grew up in Manhattan under the watchful eye of their widowed father, Samuel Ward, a Wall Street investment banker who became very religious after the death of his wife in 1824. This religiousness caused Ward to be a stern overseer of Julia’s moral training as well as the guardian of her personal safety. He kept Julia (and to a lesser degree her sisters) fairly well isolated from any corrupting frivolous outside influences and in imitation of his highly cultured dead wife – also named Julia – he encouraged his daughter in her pursuit of knowledge, which after a brief tenure at a nearby school for girls consisted of home studies with the best teachers in New York. A serious, dutiful student, Julia developed a strong affinity for languages, poetry, philosophy and music. In addition, Julia’s education was assisted immeasurably by the availability of her father’s extensive library – significantly supplemented by her older brother Sam’s collection of modern “radical” titles from Europe – and what was considered to be one of the better private art collections in the city.

When Julia was in her early teens she and her younger siblings spent a summer in Newport to escape an outbreak of cholera in New York City, staying with their maternal grandmother in a rented house near Bailey’s Beach. Newport proved to be a much needed respite from the restrictions of the family home in New York and even Samuel Ward noticed the improvement in his children’s disposition and general health, so he bought a house in town at the corner of Bellevue Avenue and Old Beach Road next to the Redwood Library, thereby commencing Julia’s yearly summer sojourns in RI’s “City by the Sea.”

After her father’s death in 1839 and her youngest brother Henry’s sudden death a year later, there was a period of confusion and depression for Julia marked by a return to the conservative Calvinist beliefs of her parents. Gradually, however, Julia started to socialize with others of her own age and with the help of her brother Sam and his wife Emily Astor, daughter of the wealthy industrialist William B. Astor, she became quite the popular invitee, noted for her witty personality, her beautiful singing voice and her ability to play the piano for dancing. Among her many suitors she was known as “La Diva Julia,” and along with her sisters Louisa and Annie she was one of the “Three Graces of Bond Street.”

It was through Mary Ward (no relation), a Dorchester, Massachusetts friend known from summers in Newport who was affianced to her brother Henry, that Julia started reaching out beyond traditional Christianity, attending lectures by Boston area transcendentalists Ralph Waldo Emerson and Margaret Fuller. These meetings and a renewed pursuit of philosophy inspired Julia to become more liberal in her religious outlook and she formed a loose affiliation with the Unitarian Church. Julia liked the intellectual atmosphere of the Bay State capital and spent more and more of her time there.

By 1843 she had met and married Samuel Gridley Howe (1801-1876), a well-connected Boston physician, also a Unitarian, who was lauded for developing a successful teaching method for the deaf and blind children at the Perkins Institute, where he was the chief administrator. Dr. Howe’s star pupil at the Institute, Laura Bridgman (1829-1889), was something of a sensation at the time – especially after Charles Dickens’ wrote admiringly of her in his 1842 travelogue American Notes, which served to cement Howe’s reputation as a champion of the disabled.

In the years before his marriage, while taking a tour of schools for the blind and deaf down south, Samuel Howe witnessed first hand the length and breadth of African-American slavery and he became an ardent abolitionist, a cause that Julia too came to support after their marriage. Besides campaigning against slavery, he was also active in various social improvement causes, including serving on committees for the improvement of public schools in Boston. An indication of this powerful, restless drive for public service can be seen in his nickname, “Chev,” which was short for “Chevalier of the Order of the Redeemer,” a title of merit awarded to Howe by the King of Greece for his youthful efforts both in fighting, and in providing medical and fundraising assistance during Greece’s war of independence against the Ottoman Turks (1821-1832).

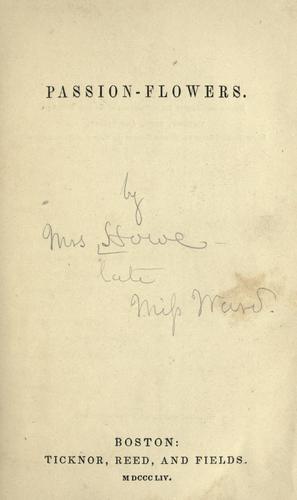

Chev was a dashing figure nearly twenty years Julia’s senior. She was attracted to his philanthropic ardor and he was attracted by Julia’s youthful beauty, intelligence and family connections. But theirs was a strained marriage with Chev pressuring Julia to be more of a traditional wifely helpmate and mother to their children, while she longed for a more active life in the public sphere as a writer, and later, as a civic lecturer and Unitarian preacher. Much of Julia’s critically acclaimed and commercially well-received poetry (her collection from 1854, Passion-Flowers, went through three printings in four months!) – as well as her later efforts for women’s suffrage – grew out of this contentious family dynamic.

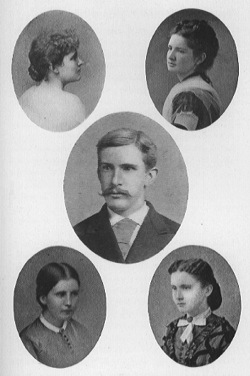

The five surviving children of Julia Ward Howe and Samuel Gridley Howe, clockwise from top left: Maude, Laura, Florence, Julia Romana and, in the center, Henry

Many of Julia’s poems from the pre-Civil War period were thinly veiled expressions of her frustration with Chev and her life as a married woman. Some poems even hinted at an emotional attachment to another man. It was seriously provocative at the time for a woman of Julia’s position in society to criticize her husband in print – even if it was in the coded language of a poem – let alone admit to being attracted to someone else. Chev would get seriously annoyed with Julia’s literary predilections, especially when her poems were explained to him by friends such as Charles Sumner, the U.S. Senator from Massachusetts famously almost beaten to death on the Senate floor after an anti-slavery speech in 1856 – a man Julia saw as a rival for her husband’s affections. There would be bitter arguments, separations, talk of divorce, and then reconciliations that would inevitably lead to another depressing pregnancy for Julia.

This opera-worthy backstory ignited a certain fascinated curiosity among the literary public of the time, especially for Passion-Flowers, Julia’s first published book. Eventually the scandal died out and her antebellum works – two collections of poetry, two plays and a recently discovered unfinished novel – were largely eclipsed by her later fame (and essentially skipped over by Julia in her 1899 autobiography). Today Julia’s writing from 1850-1860 has been revealed to be not only well crafted literature, beautifully written in an erudite, almost antique language, but also, when compared to her and Chev’s surviving correspondences, something of a window into the surprisingly complex emotional life of a well-to-do mid-19th century American family.

Title page to Julia’s first published collection of poems, hailed as “one of the benchmarks of antebellum literary achievement” by Gary Williams in his book Hungry Heart: The Literary Emergence of Julia Ward Howe (1999).

Julia and Chev’s activities centered around Boston with a home in the then wooded suburb of South Boston, which Julia had poetically – and perhaps a little ironically – dubbed “Green Peace.” They also lived part of the time in various town houses in the city itself. But Chev had a restless personality and they travelled frequently – together and separately, both nationally and abroad. Yet for all the great cities and places Julia and her family visited and lived in, only Rome, where Julia developed her poetic craft during an eight month stay apart from Chev in 1851-52, competed with Newport as the city closest to her heart – as might be gleaned from the title of one of her Passion-Flowers poems, “From Newport to Rome.”

A print of “Green Peace,” South Boston, showing where the Howes lived from 1845-1863. In a cost saving measure, the Howes moved from here into living quarters at the Perkins Institute (much to Julia’s displeasure). Chev eventually rented a town house in Boston for Julia.

Julia, born and raised in Manhattan, was a city girl at heart. Chev, however, preferred to live out in the suburbs where he could relax with gardening and landscaping, so when they had the opportunity to purchase some property on Aquidneck Island they compromised by being close enough to Newport to enjoy it’s social life, but far enough away to enjoy country living. In 1853 the Howes first purchased an old farmhouse in the southern end of Portsmouth, an area called Lawton’s Valley some eight miles north of Newport proper, and after selling that property in 1865, they later moved nearby to a summer home they called “Oak Glen.”

A painting of Julia sitting on the lawn of her Lawton Valley summer home in Rhode Island some time after 1853 (a grist mill on the property, adjacent to the family domicile, is seen in the background).

A wintertime view of Oak Glen in Portsmouth, this is where the Howe family spent their summers after 1870. The original part of the house, seen from center to left in the photo, Chev had moved to this location from another part of the property. The front of the house seen on the right was added shortly after. The low addition at the far left is from the 20th century. This site was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1978. (Photographer: Warren Jagger, February, 1977)

Julia did much during her long life to encourage cultural and intellectual activities in Newport and she witnessed its transformation from a sleepy commercial port to a Gilded Age retreat for America’s rich and famous. It could be said that it was Julia who attracted many of these people to the area with her “Town and Country” club meetings (first established as a group interested in the natural history of the Newport area but whose scope expanded to include all sorts of cultural activities during its 30 year existence) and her talks on spiritual/philosophical subjects. Perhaps because they offered a respectable diversion for the wives and daughters of the vacationing industrialists and financiers – ostensibly in Newport for summers of sea and shore – Julia’s activities were supported by the community and well attended. She also welcomed intellectuals and artists of all stripes into her circle: male and female, young and old, established and neophyte, foreign and domestic who contributed to the cultural diversity of the city at this time.

A daguerrotype of Julia Ward Howe (back row, center) and some of her literary friends, including the famous poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (in the top hat at right) and his wife Fanny (front row, center). Picture taken in Newport where the Howes and the Longfellows rented a house together in the summer of 1852.

The success of The Battle Hymn of the Republic lowered Chev’s aversion to Julia’s public speaking activities, which gradually became more frequent through the war years and beyond. However, it wasn’t until after Chev’s death in 1876 (after a long difficult bout with brain cancer) that Julia pursued a full-time public speaking career – spurred on by the discovery that bad real estate investments made through the years by her husband and others in charge of her trust had squandering much of her personal wealth. With her children mostly grown she could get by with income form her books and from a wide variety of paid speaking engagements which she took at every opportunity. And while never in poverty, she definitely had to worry about finances to some degree for the rest of her days.

You might think, considering all that she went through in her life up to the death of her husband (including an eleventh hour admission of marital infidelities on Chev’s part, which paradoxically brought them closer together during his final months of sickness) that Julia would have more than a little pro-feminist agenda in her outlook on life. Yet she unfailingly encouraged women to maintain a balance between the personal and the public, promoting women’s rights while upholding the value of traditional duties that maintained the essential character of femininity and motherhood, ideals that figured strongly in her philosophy on how to achieve world peace.

It was this balance that made her an appealing figure in late 19th century America (she wasn’t as radical as some of the other Suffragette leaders, yet she was a tireless supporter and organizer for the Suffragette cause). Indeed, in many ways, Julia was what we today would call a star, and she had a following that esteemed her to the point of reverence – helped along, no doubt, by the strong physical resemblance she developed in her later years to England’s Queen Victoria. It’s not surprising that she was frequently referred to as “America’s Queen,” and from her summer home in Portsmouth she ruled over Newport’s social intellect for much of the 19th century and beyond.

In 1910 Julia spent her last summer at Oak Glen staying there through the fall. In mid October after coming back to Portsmouth from a commencement ceremony at Smith College in Northampton, MA where she received an honorary degree (one of three she received during her lifetime – including one from Brown University, her husband’s undergraduate alma mater), Julia caught a cold that quickly turned into pneumonia and after a few days in bed she passed away.

Many websites mistakenly refer to Julia’s place of death as being Newport, rather than her home in Portsmouth (and to confuse matters further the her obituary in the New York Times reported the place of death as Middletown, RI). But considering Julia’s feeling for the City by the Sea, it may well be more correct in spirit to say Julia Ward Howe died in Newport. However, her main funeral service, attended by some 4,000 mourners, was in Boston, – the Howe Family’s official city of residence. Julia is buried in Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge along side her husband and her youngest child Sammy, who died at age four in 1863 from contracting diphtheria.

THE BATTLE HYMN OF THE REPUBLIC

Julia, as she appeared in the 1860s. From an oil painting begun by Julia’s son-in-law, John Elliott (1858-1925), but finished by William H. Cotton (1880-1958).

The melody that inspired Julia Ward Howe’s single best-known poem has its source in an early 19th century Christian camp meeting song known as Brothers Will You Meet Us? or sometimes Canaan’s Happy Shore. The prominent feature of this hymn is its refrain consisting of a threefold repetition of “Glory, Glory Hallelujah” set to the same melody as the verse. This feature was to remain constant in most of the subsequent versions of the tune over the next 50 years – and beyond. William Steffe (1830–1890), variously described as either an itinerant Christian preacher from North Carolina or a musically inclined insurance salesman from Philadelphia, claimed credit for first arranging the music for Brothers Will You Meet Us? into standard notation for use at a Philadelphia fireman’s meeting sometime in the 1850s. While his claim is unsubstantiated, it is Steffe’s name, besides that of Julia Ward Howe’s that you’ll see most often associated with this tune. Whatever its origins, the tune is thought of as a Methodist hymn due to its appearance in Methodist hymnals of the period.

In the years leading up to the start of the American Civil War the song was known both north and south of the Mason Dixon Line, but it was especially popular among the soldiers stationed in the Boston area, and it was at Fort Warren on one the islands in Boston harbor that soldiers made up new words for this old camp meeting song. These new lyrics seemed to be in honor of the controversial abolitionist John Brown, a New England native who in 1859 was captured, tried and executed in Virginia after trying to start a slave insurrection by attacking the Federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry with a small group of armed followers. These lyrics combined with the “Brothers Will You Meet Us” melody came to be known as “John Brown’s Body” after the opening line of the new lyrics. But as seen below, if this early version of the John Brown song from the Library of Congress is any indication, the song was probably just as commonly known simply as “Glory Hallelujah!”

However, after the war, published recollections by soldiers from 2nd Massachusetts Infantry Battalion, the unit stationed at Fort Warren, explained that the song was also a bit of fun being had at the expense of one of their sergeants, a Scottish immigrant conveniently also named John Brown, who sang in the unit’s glee club. There may be some truth to this, for the opening phrase, “John Brown’s body lies a mouldering in the grave,” is certainly an odd way to celebrate the memory of John Brown, the abolitionist. It may reflect more of the dark humor of men experiencing the privations of army life, releasing a little steam, making a joke around the shared name of the two John Browns than it does of ending slavery. Yet for all that, the gruesome imagery of the opening lines does make for an effective contrast between the executed abolitionist, who some in the North considered a martyr, and his ideals which “go marching on” despite his death. However, subsequent images in the song, like that of John Brown “with a knapsack on his back,” might well refer to sergeant John Brown.

The lyrics to John Brown’s Body were soon published on broadsheets, first in Boston and then in other Northern cities. But all of these are thought to be cleaned-up versions of what the soldiers actually sang. For instance many of the barbs pointed at poor sergeant Brown were redirected toward Confederate soldiers and in particular, Confederate president Jefferson Davis. It is very likely that Julia Ward Howe would have heard John Brown’s Body sung by soldiers, or she would have at least read the printed broadsheets, when the song first appeared in Boston. She might have even heard the brass band arrangement put together by the renowned Boston bandleader of the time, Patrick Gilmore. Being musically inclined, she certainly could have easily learned the tune, and she would have had opportunities to sing it at the abolitionist meetings she and Chev were organizing. At any rate according to her autobiography, by November of 1861 Julia claimed some degree of familiarity with the song, telling her friends she “had long been of the opinion” that the lyrics of John Brown’s Body needed improving. All of which plays into the story as follows.

According to the story presented in Julia’s autobiography Reminiscences, 1819-1899 (and repeated verbatim by nearly every printed and web-based source since), it was in the Fall of 1861 while she was in Washington D.C. with her husband and some of his associates from Massachusetts on the newly formed Sanitation Commission, a group charged by the Federal government to oversee the health standards of the Union army camps, that she found the inspiration to write the Battle Hymn lyrics. It was during an excursion to witness a military review of Union troops, Julia and her friends (but not her husband Chev, who was elsewhere) became stuck in traffic on the road back to the city after a sudden dispersal of the assembly due to the nearby presence of Confederate forces. To pass the time she and her friends sang inspirational songs, including John Brown’s Body, as they waited in their carriage. Julia remarked that the soldiers who passed by on the road had apparently never heard the John Brown song before and thought it good, joining enthusiastically on the “Glory, Hallelujah” refrains. It was after they had finished singing that the group of friends agreed that the “John Brown” lyrics were not a noble enough reflection upon what was now a great struggle for the cause of freedom.

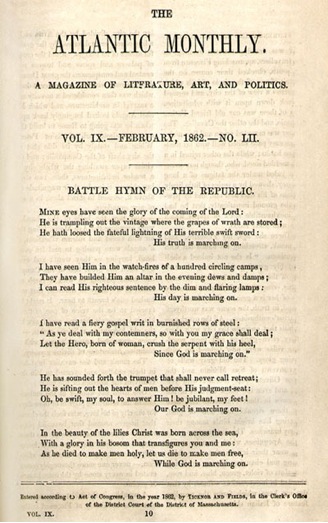

One of the passengers in the carriage was fellow Sanitation Commissioner James Freeman Clarke, who was also the pastor of a Unitarian congregation in Boston whose services Julia frequently attended. Clarke supposedly challenged Julia to write better lyrics for the song, which she did late that night back in her Washington hotel room through what she described as a kind of visionary experience, scribbling the lyrics in the dark with the tune of John Brown’s Body still ringing in her head. Julia sent her poem, entitled “Battle Hymn of the Republic” some months later to The Atlantic Monthly magazine (for which she was famously paid $5), which published the poem (anonymously at first, which was typical of many of Julia’s early works) in its February 1862 edition. Reprints spread like wildfire across the North – and because it was anonymous (and copyright being what it was in those days) Julia received no recompense for any of the reprinted editions. Some of the later reprints indicated “John Brown’s Body” as the melody for the song and the Battle Hymn as we know it today was born.

I was curious, however, to find out what James Freeman Clarke thought of the song, since Julia claimed it was at his insistence that new lyrics be written. To my surprise in his published recollections and letters (edited posthumously in 1889 by Edward Everett Hale), Clarke makes no mention of the “Battle Hymn” at all. He does recall his trip to Washington in 1861, made with “Colonel Howe” and a group of unnamed friends, remarking upon a set of war related things similar to those described by Julia, including: witnessing (from a safe distance) a Confederate skirmish with Union soldiers, being part of a review of Union troops in the field, visiting the Massachusetts units in their campgrounds – and hearing them sing John Brown’s Body, whose lyrics he wrote down admiringly in his journal. However, there is no mention of any carriage ride sing-along with roadside soldiers, or any mention of improving the words of John Brown’s Body.

Even beyond this lack of corroboration from Clarke, there might be some questions about Julia’s version of the events. After all, Clark was, along with Julia’s husband, one of the so-called “Secret Six,” the financial backers of John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry attack. It just doesn’t seem likely to me that Clarke would encourage Julia to rewrite the lyrics to a song in honor of John Brown, especially in such a way as to remove his name entirely. Plus, there is no mention by Julia of her submitting the “improved” John Brown lyrics to Clarke for his opinion or approval – also odd if it was his idea.

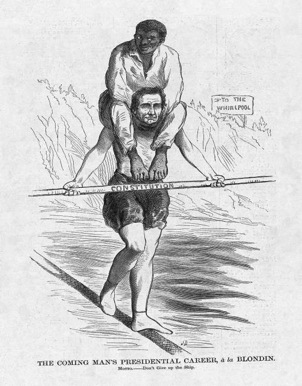

All this begs the question: Why would Julia feel the need to remove John Brown from his namesake song? Was it part of what author Annie J. Randall called, in an 2004 article, a type of censorship by people of power and rank on the Union side, who felt uncomfortable with the radical image of John Brown – perhaps fearing as much as any Southerner what freeing the African-American slaves would actually mean? The political cartoon below illustrates the trepidation felt by many Northern whites at the beginning of the Civil War in regards to emancipating the Southern slaves. A feeling that might lead even an abolitionist like Julia Ward Howe to censor or somehow lessen references to the extreme – some would say unbalanced – John Brown and his vision of a violent overthrow of slavery in this country.*

*After the 1860 election: Abraham Lincoln’s balancing act in respect to slavery is compared to that of the famous French daredevil Blondin, who during the 1850s would cross Niagara Falls on a tightrope with his 160 lbs. agent Henry Colcord on his back.

Given her mother’s “Swamp Fox” Southern heritage, Julia perhaps understandably felt some discomfort singing John Brown’s Body. But it’s possible that as a poet she judged the lyrics were indeed not noble enough for the cause of freedom. Despite what you see of her in pictures, Julia was reputed to have keen, mischievous sense of humor, and she would have immediately picked up on the soldierly humor of the song’s lyrics and, while appreciating the humor, she might have been somewhat embarrassed by it as well. But from my point of view, I suspect that after she heard the soldiers enthusiastically joining in on the “Glory, Hallelujah” refrains, the musician in her wanted to take advantage of a good tune toward a more serious purpose. (I can’t picture Julia singing “We’ll feed Jeff Davis sour apples ’til he gets the diahree,” one of the funnier variants of the John Brown’s Body verses).

But whatever the reason for the rewrite, why did she feel the need to credit the idea to James Freeman Clarke and why does her version of their time together in Washington differ from his? Once again I suspect that Julia, for the sake of a good story, conveniently condensed the time frame for the various activities she and her friends experienced that November in 1861 – and so as not to appear too “uppity,” she simply transferred her idea of improving the John Brown song to her Unitarian minister friend, who was a well-respected member of Boston society and an associate of her husband, working together in the Sanitation Commission, helping the war effort for the Union cause.

The “uppity” woman is certainly an image that even today still plagues women in the male-dominated world of political, economic and educational power structures. So you can imagine how things were in Julia’s day, when the image of a masculine or self-directed woman was an especially alien one to respectable society. And Julia most certainly had personal reasons for being circumspect, for as close as she ever came to being “masculine” with her desire to be effective in the public arena, any such interpretation of her activities would have been a source of friction in her marriage and an embarrassment to her children (who after her death actually destroyed many of Julia’s letters to and from her husband in an effort to ensure the saintly reputation of their parents).

In many ways Julia’s life was a balancing act, not unlike that of Lincoln’s political career as depicted in the cartoon above. She promoted feminist ideals on one hand while projecting herself as a paragon of motherly femininity on the other, so her oft-repeated story about the creation of the Battle Hymn just might be a case of Julia covering her steps a bit. She may not have wanted to overshadow Chev’s wartime activities, or his memory after his death. But in spite of the differences, since Clarke’s published recollections do not reject Julia’s version outright, in the face of more research, we may accept Julia’s Battle Hymn genesis story – with, perhaps, a grain of salt.

The Battle Hymn as it first appeared on the first page of the Atlantic Monthly. Notice the absence of Any “Glory Hallelujahs.” However, readers familiar with John Brown’s Body would have immediately recognized it as the poem’s metrical source from the “marching on” refrains at the end of each stanza.

THE BATTLE HYMN FROM 1861 TO TODAY

No matter how the Battle Hymn came to be, Julia Ward Howe was obviously inspired by the surreal, end-of-the-world feeling in and around Washington D.C. during the early – and from the Union perspective, the most uncertain – part of the American Civil War, creating a set of lyrics that was in her opinion “far better than anything I had ever written.” She met Abraham Lincoln during her time there and was greatly impressed by him, she saw the soldiers in their evening camps, she witnessed, however distantly, the sound of battle, she could see the mortuaries and the effects of the killing fields spread throughout the city. She built her poem around these images to create an indictment of the current state of her world.

However even though Julia was a supporter of the abolition of slavery, albeit only after her marriage to Chev, she chose to remove John Brown as the agent of the Apocalypse. In the rarely sung third stanza she vaguely cites a “Hero born of woman” who will execute God’s justice. In subsequent verses, however, the plea to do God’s work becomes at first a personal one, “be swift my soul to answer Him, be jubilant my feet” – and then in conclusion with a reference to Jesus Christ it becomes universal, “as He died to make men holy, let us die to make men free.” The title “Battle Hymn of the Republic” seems to have added as an afterthought, and some references claim that it was an editor at the Atlantic Monthly who gave the poem its title. But the poem, so-titled, was interpreted by the magazine reading public of the North as a call to action in support of the Union.

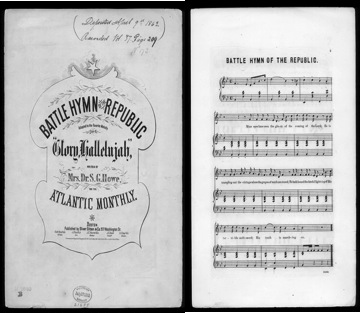

Two pages from the first sheet music edition, published by Oliver Ditson and Co., Boston in April of 1862. Interestingly credited to “Mrs. Dr. S. G. Howe,” unlike most other married women of the time, Julia always used her own given and maiden names as part of her married name.

One would think that a “battle hymn” would have a limited life span, especially as the nation tried to heal after the war. And of course Southerners wishing to honor the memory of their Confederate ancestors would understandably think twice about this song knowing that God’s “terrible swift sword” and His “trumpets that shall never call retreat” was being invoked against the cause of their forefathers. But Julia wrote the lyrics – which for the most part paraphrased parts of the Bible, the Book of Revelations in particular – without being specific as to who was right and wrong, unlike the lyrics the Union soldiers made up for John Brown’s Body. There was some wiggle room as to the implications of singing The Battle Hymn of the Republic. Indeed if the song was written at any other point in her life the same lyrics could just as easily represent Julia’s well documented support of European democratic movements, like those of Italy and Hungary in the 1840s and 1850s, as well as her support for Armenians in their struggles with Turkey in the 1890s.

Being one of the great marching tunes of the war, both the John Brown song and its more noble cousin, the Battle Hymn, would have been sung by the Union veterans with all the passion of those who’ve been through the hell of battle, with a slight preference given to John Brown’s Body – at least while on the march since it’s easier to sing with fewer words crammed into the verse. The veterans’ enthusiasm for the Battle Hymn transferred to the general public and due to her fame as the song’s author, that intensity of feeling followed Julia everywhere she went during her frequent cross country public speaking tours. She would inevitably be asked to tell the story of the creation of the Battle Hymn and/or recite the lyrics, and her audiences would spontaneously burst into rousing versions of the song at her introduction to almost any meeting she attended – especially toward the end of her life.

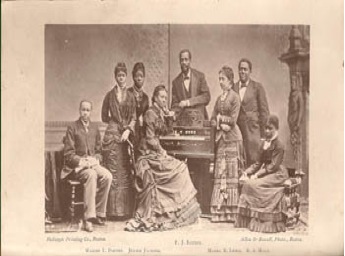

The Fisk Jubilee Singers, who famously sang the Battle Hymn at the 1872 World’s Peace Jubilee in Boston: a prominent example of African-Americans’ affection for the song.

Coming full circle given its evangelical and Methodist hymnal origins, the Battle Hymn took root as a religious anthem, and unsurprisingly given Julia’s abolitionist credentials, it has become especially popular with black church congregations (many of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s speeches quote freely from the Battle Hymn of the Republic). That the song was accepted even among Southern whites is no doubt due to the fact that from the Reconstruction period right on up to the present, Americans have chosen to interpret the song patriotically rather than apocalyptically, letting it stand for all of us against any form of repression or danger – as it did most famously in the memorial services in Washington after the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks. But as some commentators have suggested, for all its religious imagery, the song does not exhibit the Christly virtue of forgiveness, and they question its value as a Christian hymn.

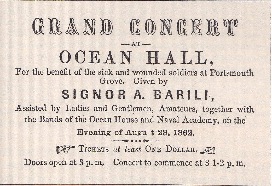

Perhaps the first full arrangement of the Battle Hymn for soloist, chorus and instrumental accompaniment was created in Newport, RI as part of a benefit concert for wounded soldiers recovering at a hospital in Portsmouth, near the Howe family residence. This was in August of 1862 – some six months after the publication of Julia’s poem. Julia was on the organizing committee for the event and she was in tearful attendance as her song was performed – a last minute addition to the program. A reproduction of the ticket for this event, taken from This Was My Newport by Julia’s daughter Maud Howe Elliott, is represented below.

Yet the most popular arrangement of the Battle Hymn is by the choral director and composer Peter J. Wilhousky, a Ukrainian immigrant from Chicago, who is perhaps best known as the creator of the Christmas standard, Carol of the Bells. Wilhousky’s 1944 setting of the Battle Hymn did much to soften the song’s tone of religious retribution, and if you witness any school or civic group performance of this tune today it is most likely his version you’re hearing.

Wilhousky’s arrangement starts out with distant drum and bugle call effects – slightly dissonant, building up and gradually fading out just before the male voices of the chorus enter with the first verse. Anyone familiar with the Battle Hymn in it’s original form would notice right away that the melodic rhythm of the first half of the song has been stretched to twice its original length. While on one hand this helps the listener to hear the text clearer it also draws attention away from the violent images in Julia’s poem by shifting the focus to the occasional fanfare figures that jump out of the faster march-like musical underpinning. As the men finish singing the first verse, the women enter singing “Gloria” as a bridge into the refrain, and this interjection is repeated at points throughout this section.

“Gloria” is a more easily sung word with it’s open “a” vowel than “Glory” is with its closed “ee.” This too shifts focus away from the imagery of war and retribution by projecting sweet sounds of vocal musicality. After a short instrumental interlude the female voices take over for the second verse, still in the slower melodic rhythm, but now now accompanied by the men singing “Truth is marching” over and over again in a rhythmic vocal ostinato that further focuses attention away from what the women are singing. Plus a third element is added here – an element of jollity – with Wilhousky’s insertion of high pitched musical quotes from “The American Patrol, ” an 1885 march by F.W. Meachum that perhaps not coincidentally was a hit for the Glenn Miller swing band in 1941, just a few years before this arrangement was written.

The emotional climax of the piece comes in the third verse, after a short, turbulent instrumental interlude where the forward motion slows and halts and the men take over, breaking into four-part harmony for a sustained acappella rendering of the least violent verse of the song – “In the beauty of the lilies, Christ was born across the sea.” And here is where you may notice a subtle but telling change that choral directors have made from the original poem – and indeed from Wilhousky’s printed sheet music. It has become common since World War II to substitute the words “As He died to make men holy, let us live to make men free” for the original’s “let us die to make men free.” Even when passionately sung, this change is in reality another softening of Julia’s Civil War era apocalyptic vision. The piece ends in a broad, stately tempo for the final refrain – building, to an all-consuming “Amen” (a word significantly not found in Julia’s hymn).

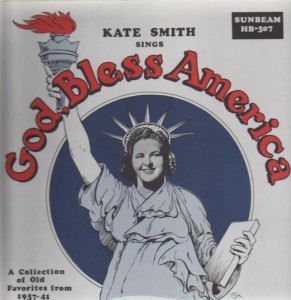

In spite of its long standing use as our country’s unofficial national hymn and its prominent place in both the official 9/11 memorial service at the National Cathedral in Washington, D.C. and President Barack Obama’s second inauguration ceremony, recent years have seen the Battle Hymn eclipsed by Irving Berlin’s God Bless America as our most commonly performed national song of reverence. Berlin’s greeting card quality lyrics seem to go down easier with today’s multi-religious and/or vaguely religious American society, and despite God’s presence in the title and opening line, the words to God Bless America are more patriotic than religious, with references to mountains and prairies, “and the ocean white with foam.”

Musically the tune is more compact than the Battle Hymn, consisting of a single 32-bar refrain – its one short introductory verse is hardly ever performed – and Berlin’s harmonic movement is far more varied and complex than the simple folk-song chords of the Battle Hymn. With its gradually rising melodic contour and dramatic high point reminiscent of a Broadway show-stopper, God Bless America has become a favorite of choruses and a vocal showcase for solo singers. It is performed everywhere from country churches to baseball stadiums. At Fenway Park in Boston, since 9/11, God Bless America has been inserted into the “seventh inning stretch” as a patriotic sing-along just before the ballpark organist plays Take Me Out to the Ballgame.

EPILOGUE

In 1970 Julia Ward Howe was entered into the Songwriters Hall of Fame, an honorary society whose physical museum is now in Los Angeles. This organization was started by pop songwriting legend Johnny Mercer in 1969 and the fact that Julia was honored one year later in the Hall of Fame’s second year of existence says something about the cultural importance of her Battle Hymn (Bob Dylan didn’t get in for another 12 years!). However, I’m sure Julia did not think of herself as a songwriter, there’s no record of her actually singing her song in public, and when called upon she would simply recite it as a poem. Yet she certainly enjoyed the singing of the Hymn by others, as she did at that early public performance of the Hymn in Newport during the summer of 1862.

It would probably never occur to Julia to promote her piece through music publishing, and for that reason alone she should not be considered a forerunner to today’s singer-songwriters, but within two months of the printing of the poem by the Atlantic Monthly the first sheet music versions began to appear with her name attached. It would seem that the song that had written itself (and continues to write itself) was molded by a woman who was certainly more than just a poet whose words were set to music by others – the way Francis Scott Key’s were for The Star-Spangled Banner. Unlike Francis Scott Key, Julia had a specific tune in mind as she wrote the words to her most famous creation, that tune being John Brown’s Body. Writing new words to a melody not of her own creation puts her more in league with church musicians who frequently are called upon to match new words to hymn tunes with which the congregation is already familiar. Julia, who saw old time religion as a springboard to understanding abstract philosophy, would I think have been comfortable with that association.

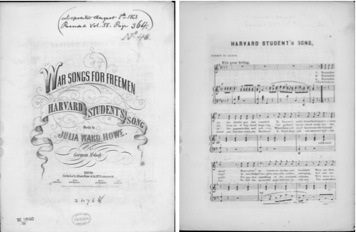

In 1863, Julia wrote the lyrics for a second war song, this time for the students of Harvard University, where Chev earned his medical degree. Like the Battle Hymn, Julia fit her words to a pre-existing melody – in this case “Denks du Daran,” a German student song she learned from her older brother Sam Ward, who studied in Europe, earning a doctorate degree from the University of Tübingen.

Meanwhile the “Brothers Will You Meet Us/ John Brown’s Body/ Battle Hymn” melody has marched on in all sorts of permutations – honoring everything from labor unions (“Solidarity Forever!”) to student rebellion (Glory, Glory hallelujah! Teacher hit me with a ruler!”). My favorite, discovered in the course of writing this article, is called “Blood on the Risers,” created by U.S. Army paratroopers during World War II (“Gory, Gory what a helluva way to die!”), the sentiments of which probably come closest to those of the Civil War soldiers in Fort Warren when they made up their John Brown song.

This simple melody has a worldwide reach, and it can be heard in almost any corner of the globe, sometimes with Julia’s original words in English and at other times in translation – or newly composed to suit local needs. A recent example of experiencing newly composed lyrics for this melody can be revealed by reading the blog of Dr. Mark Conley, Director of Choral Activities at the University of Rhode Island concerning his three month stay in a north central area of Mozambique during the summer of 2013 where he helped to prepare various church choirs and community groups for participation in a local choral festival. During his travels, Dr. Conley witnessed a funeral in a family home where the deceased was laid out before burial, and as the people paid their respects they began to sing a hymn tune that was immediately recognizable to Dr. Conley as a local variant of the John Brown/Battle Hymn melody with what he assumed to be new words suited to the occasion. More often than not, however, non-English speaking people – evangelical Christians especially – will sing just the “Glory, glory hallelujah” refrain (over and over again in some cases) making it an essential part of their religious experience.

In any language this melody is without a doubt the U.S.A.’s best-known musical accomplishment, perhaps this country’s greatest contribution to the world repertoire of song. And Julia Ward Howe should be remembered for her part in that contribution – indeed her colorful and eventful life would make for a great multi-part televised drama (are you listening BBC America?). In fact this article for the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame website is in reality just one very long question (with illustrations) – Why isn’t there a monument worthy of this woman’s achievement in the city and state that she loved so well and so long? Hopefully the answer will be forthcoming.

AUDIO/VISUAL LINKS

The basic repertoire

Keith & Rusty McNeil “Say Brothers Will You Meet Us?” from American Religious Songs (Disc 1 of 3). This is a recreation of the earliest known version of this melody.

Pete Seeger “John Brown’s Body.” These are the most common verses sung for this song. At the very end Seeger throws in the first verse of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” giving us a good contrast between the straight ahead lyrics of “John Brown” and the wordy text of the Battle Hymn.

Odetta “Battle Hymn Of The Republic.” An acappella gospel quartet version of the entire hymn – but with each verse and refrain ending with “His truth is marching on” unlike Julia’s poem, which has “God is marching on” (or some variant) after the first verse and refrain. This focus on “Truth” shows up on most of the modern versions of this song.

Mormon Tabernacle Choir and Orchestra “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The gold standard performance for Peter J. Wilhousky’s arrangement.

Maine All-State Chorus 2012 “Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The Wilhousky arrangement as most people experience it: sung by a high school chorus, accompanied by piano.

Singing Sergeants of the US Air Force Band performing a contemporary version of the Battle Hymn by the English composer John Rutter, arranged for mixed voices and concert band. This keeps to the original rhythm of the Battle Hymn and includes the rarely heard third verse.

“Blood Upon the Risers (Gory, Gory What a Helluva Way to Die).” This World War II vintage version was created by paratroopers in the 101st US Army Airborne Corps, written in the same vein of irreverent “black humor” as the original versions of “John Brown’s Body.”

The outward reach

The Choir of Trinity College, Cambridge “John Brown’s Body.” A modern acappella choral arrangement performed by this English group.

Drakensberg Boys’ Choir “2010 Battle Hymn of the Republic.” The John Rutter version arranged for boys’ voices, piano and percussion – performed by a group from South Africa.

Jorge Razetto “Gloria Gloria Aleluya.” A Christian hymn with new lyrics sung in Spanish.

Celine Dion “Glory Alleluia.” A live televised performance with her family, it’s the Battle Hymn adapted for the Christmas season with new lyrics sung in French by a young pre-diva Dion.

Mireille Mathieu “Trois Milliards Gens sur Terre.” A song for world peace with new lyrics sung in French.

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic.” Julia’s words sung in English by an unidentified choir at the Concert Gospel, Chalon sur Saône, France – May 2011.

Juha Watt Vainio “Kalle Kustaa.” The Battle Hymn as a polka, with new lyrics – Wikipedia says this is a marching song for the Finnish army.

Recent versions

Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir. An original arrangement of The Battle Hymn created for the group to sing at President Obama’s second inauguration. The frequent changes of key and sudden chord substitutions make this version – with all its Hollywood glitz – a good representation of our restless and troubled times.

Two idiosyncratic, gospel-informed versions of the Battle Hymn: Whitney Houston in 1991 (honoring U.S armed forces personnel returning from the first Iraqi conflict), and Elvis Presley in a 1973 televised concert from Hawaii as part of his American Trilogy showstopper. In Elvis’ case only the refrain is sung.

Points of history

Libby Franck as Julia Ward Howe. An informative, brief dramatic overview of Julia’s life up to the writing of the Battle Hymn.

Gloria Steinem, Vanessa Williams, et al. “Mother’s Day for Peace.” A multi-performer reading of Julia’s 1870 Mother’s Day speech. It is one of many ironies in Julia’s life that her best-known work celebrates “the just war,” while she herself campaigned for world peace via speeches like this one.

Martin Luther King, Jr. “I’ve Been To The Mountaintop” speech. The last public words ever spoken by the Reverend King were quoted from the first line of the Battle Hymn of the Republic.

National Park Service. The story behind John Brown’s Harper’s Ferry raid.

REFERENCES

Print Sources

Clarke, James Freeman. Autobiography, Diary and Correspondence, edited by Edward Everett Hale. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Co.; Riverside Press, 1891.

Clifford, Deborah Pickman. Mine Eyes Have Seen The Glory: A Biography of Julia Ward Howe. Boston and Toronto: Little, Brown and Co., 1979.

Elliott, Maude Howe. This Was My Newport. Cambridge, MA: Mythology Co./A. Marshall James, 1944.

Graves, Mary H. “Julia Ward Howe,” Representative Women of New England, Julia Ward Howe and Mary H. Graves, eds. Boston: New England Historical Publishing Company, 1904.

Howe, Julia Ward. Original Poems and Other Verse Set to Music as Songs. Boston: Boston Music Co., 1909.

Howe, Julia Ward. Reminiscences, 1819-1899. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Co.; Riverside Press, 1899.

Howe, Julia Ward and Rosalys Hall. Flibberty-Gibbet’s Jig, woodcuts by Ilse Buchert Nesbitt. Newport, RI: The Third & Elm Press, 1987.

Randall, Annie J. “A Censorship of Forgetting: Origins and Origin Myths of ‘Battle Hymn of the Republic'”, in Music, Power, and Politics, edited by Annie J. Randall. New York: Routledge, 2005.

Richards, Laura E. and Maude Howe Elliott, with assistance from Florence Howe Hall. Julia Ward Howe, 1819-1910. 2 vols. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1915.

Stouffer, John and Benjamin Soskis. The Battle Hymn of the Republic: A Biography of the Song That Keeps Marching On. New York: Oxford University Press, 2013.

Williams, Gary. Hungry Heart: The Literary Emergence of Julia Ward Howe. Amherst, MA: University of Massachusetts Press, 1999.

Ziegler, Valerie H. Diva Julia: The Public Romance and Private Agony of Julia Ward Howe. Harrisburg and New York: Trinity Press International, 2003.

Online (Selected Sites)

Atlantic Online. Battle Hymn – Original electronic resource (Accessed Aug. 31, 2013).

Boltz, Martha M. “Battle Hymn of the Republic” from Yankee song to national hymn? from Washintgton Times website (2010).

Brent, Hugh. Learning History: John Brown’s Body from DigitalHistory website (2013).

Conley, Mark A. Death in Cobué from Intrepid Conductor weblog (June 17, 2013).

Criswell, Chad. Battle Hymn of the Republic from Suite101 website (2013).

Goodwin, Joan. Julia Ward Howe from Unitarian Universalist History and Heritage Society website (2013).

History50States.com. History of Middletown, (Butler County) OH – Shobal Vail Clevenger Biographical Sketch article (accessed Aug 25, 2013).

JuliaWardHowe.org. Julia Ward Howe: Biography article (accessed Aug. 24, 2013).

Kennedy, Pamela and Richard Harrington. “Oak Glen” nomination form for the National Registry of Historic Places found at Rhode Island Historical Preservation and Heritage Commission website (1977, accessed Aug. 25, 2013).

Kennedy, Robert C. Cartoon of the Day: “The Coming Man’s Presidential Career – a la Blondin” from Harper’s Weekly website.

Library of Congress:

Music Score: Glory! glory! hallelujah! electronic resource (accessed Sept. 31, 2013).

Music Score: Battle Hymn of the Republic electronic resource (accessed Sept. 31, 2013).

Music Score: Harvard Student’s Song electronic resource (accessed Sept. 31, 2013).

Morgan, Kenneth J. The Truth About the Battle Hymn of the Republic from Rediscovering the Bible website (2008).

National Portrait Gallery. American Women: Julia Ward Howe article (accessed Aug. 25, 2013).

Ortner, Eric. The Cornet and its Civil War Virtuoso Patrick Gilmore from Ortnergraphics website (2012).

SongwritersHallOfFame.org. Early American Song: 1600-1879 – Julia Ward Howe biography article (accessed Aug. 24, 2013).

Soskis, Benjamin. A Fiery Gospel: How the “Battle Hymn of the Republic” changed America—and the life of the woman who wrote it 150 years ago from Slate website (2011).

Stinson, Brian. Newport Notables: Julia Ward Howe timeline from Redwood Library & Athenaeum website (2004).

Senate.gov. U.S.Senate: Art and History – General Marion Inviting a British Officer to Share His Meal article (accessed Aug 27, 2013).

Wikipedia.org:

John Brown’s Body article (2013).

Julia Ward Howe article (2013).

Samuel Cutler Ward article (2013)

PDFs OF SONGS

Foreword

Music has always played an important part in my mother’s life. In her girlhood she studied the piano with a pupil of Cramer, while her voice, a fine soprano, received careful training from Cardini, an intimate friend of Garcia, whose method he employed. She gave some attention to the study of harmony, but the songs that she has composed from time to time have been rather native bird notes than the result of study. It has always been as natural for her to sing as to speak, and when she has needed a melody to fit her own words or those of another, she has simply made it.

At the earnest wish of her children and grandchildren, she has now consented that some of these songs should be published. Composed at intervals through a period of seventy years, they reflect varying moods of the different phases of a long life and it is hoped that they may interest others besides her immediate family and friends.

– Laura E. Richards.

Please click on the following link to see PDFs of the songs in this collection:

https://uri.libguides.com/music-resource/julia-ward-howe