Frank Potenza

2017 INDUCTEE

Jazz, Music Educator

FROM THE OCEAN STATE TO THE CITY OF ANGELS

The Musical Journey of Jazz Guitarist

FRANK POTENZA

FRANK POTENZA: AN INTRODUCTION

FRANK POTENZA: AN INTRODUCTION

by Rick Bellaire (2017, 2021)

After graduating from the Berklee College of Music in 1972, Providence jazz guitarist Frank Potenza launched parallel careers as a performer and an educator appearing regularly with the area’s top jazz and blues artists and teaching at the Rhode Island School of Music. He moved to California in 1980 and quickly established himself on the West Coast scene performing and/or recording with a “who’s who” of jazz greats including his mentor, Joe Pass as well as legendary pianist Gene Harris and teaching at Long Beach City College and the Flora L. Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California. His career skyrocketed after signing with TBA Records in 1986. His first four albums placed high on Billboard’s Jazz and Contemporary Jazz charts with his second, Soft & Warm, reaching the Top Ten. Since the time of his induction into the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame in 2017, Frank has remained a dedicated music educator and held the position of Chair of the USC/Thornton Jazz Guitar Program until he stepped down in 2018. His latest album, For Joe – his homage to Joe Pass – was released in 2013 and received a four star review in Downbeat.

FRANK POTENZA IN HIS OWN WORDS

Oral History Interview Conducted and Recorded

by Allen Olsen and Rick Bellaire

March 27, 2022

THE EARLY YEARS

Allen Olsen: It’s March 27 of ’22, and I’m sitting here in Charlestown, Rhode Island. Rick Bellaire is sitting there in Providence, Rhode Island. Today we have Frank Potenza, 2017 inductee of the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame – in what town in California, Frank?

Frank Potenza: Lakewood.

Allen: So, here we are and today we’re going to interview Frank. We usually start at the beginning, Frank, with this: please tell us where you were born, when you were born, and a little bit about your family and neighborhood.

Frank: I was born in Providence, Rhode Island on February 10, 1950, in the Wanskuck section of Providence.

Rick Bellaire: That’s where Peter and Vini – Pete Anders and Vini Poncia [2012 RIMHOF inductees] are from – Wanskuck-Eagle Park – that area.

Allen: Oh! Connection.

Frank: I never knew them. I certainly knew of them, but I never knew them. They’re a little older than I.

Rick: Much older; nearly ten years older than you.

Allen: Can you tell us a little bit about your family and neighborhood, Frank?

Frank: Yeah. It was very middle class. My mother and father loved music. My mother – when my father was away in the war [WWII] moved into the third floor of a tenement that we all grew up in, in Providence, in Wanskuck there. And the first piece of furniture they moved in for her was an upright piano to the third floor. She taught herself to play. She just played by ear. And we thought she was a genius. She could play anything. Not in any key – I’m pretty sure she stayed close to the key of C for the most part. But she figured out enough on her own to be able to – and she had a good enough ear – that she could play anything on the piano you asked her to. She could pick it out. And then, she’d play something in the way of a left- hand accompaniment that was sometimes on the money, and sometimes not on the money. It was sort of an ersatz stride kind of bass. [mouths piano bass] And the harmonies in some cases worked, and in some cases didn’t. The bass notes, in some cases, were the root and the downbeat. But we thought she was a genius. We just thought she could do anything. My father was a big band fan, and he liked the Mills Brothers and Frank Sinatra and all that stuff. He had a huge what was called a “combination” – it was a phonograph and a radio, like a [radio] tuner, and he had a record collection. They just both loved music. And so, they had six kids and basically made it possible for all six of us to have careers – not necessarily [professional] careers – but to have instruments and music lessons or whatever. It was something that they were way into, and they couldn’t support enough.

Allen: And what did mom and dad do for a living, Frank?

Frank: My mother was a housewife, and my father worked like sheet metal – air conditioning, duct work, that kind of stuff.

Allen: So, would you say that mom and dad were the initial influence for you wanting to play music?

Frank: Yeah. And my oldest sister had had somewhat of a run; like a childhood local star on WJAR radio [the Providence, Rhode Island NBC affiliate]. When she was a very young, young girl, she had this name, “Baby Boots,” and she used to sing on the radio, on WJAR. And there was some kind of regular programming. I don’t know if it was weekly or what. I don’t know how long it went on.

Ed. The show was The WJAR Kiddie Revue directed by Celia Moreau, a local piano teacher, who discovered and nurtured the talents of local children for a weekly variety show. It featured singers, tap dancers, instrumentalists etc. and ran from 1930 into the early 1950s. Dorothy Potenza Welch, whose stage name was Baby Boots, was a featured performer on the show as a young child. Other participants included accordionist Dick Domane who went on to become the keyboard player and one of the lead vocalists for The Blue Jays/White Water, singer-dancer (and future mayor of Providence) Vincent “Buddy” Cianci, and announcer Art Lake who later became a weatherman for the WJAR NBC-10 television news.

She was another huge part of my development – she played ukulele later in life and could accompany herself – and she taught all of us – my two older sisters and myself – how to play chords on the ukulele. “Five Foot Two [Eyes of Blue]” and that sort of stuff. So, that was kind of my first contact with an instrument.

Rick: What was “Baby Boots’” actual name?

Frank: Dorothy. “Dot,” we called her. And so, she was the one who taught me how to play ukulele. And she also, in later years – like in the late fifties, early sixties – owned and operated a school of dancing which was right around the corner from my mother’s house – literally three houses away – that we all went to, and we all participated in. My mother was the quintessential stage mom. She loved show business; loved music. She would set up a curtain in the living room, and we would have shows and she’d play the piano. She couldn’t get enough of her kids being involved in music, and it just inspired all of us to take musical instrument lessons, and to play music. And eventually, myself and my two brothers [Joe and Jery Potenza] actually have professional careers as a result of it.

Allen: And when did you start to formally take lessons, Frank?

Frank: Well, I was told that I took some piano lessons as a very young person, which I don’t recall at all. I don’t think it was very many, but I…

Allen: You were very young.

Frank: Yeah. Like first grade, or something like that, with the nuns. I went to Catholic grammar school.

Rick: What was the school?

Frank: St Edward’s School on Branch Avenue in Providence. But I looked this up, ‘cause I wanted to be sure about the years. I actually took accordion lessons with Joe Petteruti, Bob Petteruti’s [2015 inductee] brother.

Ed. The Petteruti family operated the Twin City Music stores in the Olneyville section of Providence and in Pawtucket; they sold musical instruments and offered instruction on a wide variety of instruments.

Rick: Wow!

Frank: And at the same time, my sister studied guitar, took guitar lessons, with Bob Petteruti who we just lost. [Mr. Petteruti died on March 11, 2022.] I took those [accordion] lessons from 1958 – I think it was April of ’58 – and the last lesson – because he wrote in the book, I have the books in my closet here and he wrote down the dates – and the last lesson was February 1 of ’61. So, for the better part of three years, I took accordion lessons with Joseph Petteruti.

Rick: Were you at the Olneyville or Pawtucket location?

Frank: Well, I started at Olneyville, but then eventually I used to go to Pawtucket more. To the best of my memory, I think I probably took more lessons in Pawtucket.

Allen: In addition to beginning formal training, Frank – radio, records – what influenced you at a young age – what grabbed your attention?

Frank: Well, radio; popular music. There was always a radio on in the house or in the car. Actually, when I was a kid, I had a paper route, and I bought one of those bigger, portable radios on time [payments] from City Hall Hardware in downtown Providence. I actually made payments on it with money from my paper route. So, we listened to music, pop music. WICE; WJAR…

Rick: [W]PRO…

Frank: …PRO, exactly. But you know, the early life stuff was mostly just an influence of the family thing. We sang. We danced. We tap danced. Ballroom danced. We did recitals. We did a couple of recitals downtown at – I don’t know if it’s still there – the Plantations Club Auditorium across from Axlerod’s [Music] on Weybosset Street.

Ed. In fact, it is still there. Although the Providence Plantations Club, a women’s rights society, disbanded in 1962, the historic building which housed the club still stands and is now called Wales Hall, a facility of Johnson & Wales University which houses the fitness center; business, counseling and other offices; and the Pepsi Forum auditorium.

The Potenza sisters, Dot, Lana and Norma on stage with brother Frank on the ukulele in the late 1950s

Frank: That was the beginning of public performance. And again, the accordion was something that was a popular instrument, and I chose that. God knows why.

Allen: Popular at the time.

Frank: Yeah.

Allen: And now, moving ahead, when did things start moving in a more formal direction in terms of music theory and application?

Frank: We studied reading and theory and all that stuff at Petteruti’s. I mean, that was all reading music and theory. That was actually my first contact with reading music. My sister quit the guitar before I quit taking accordion lessons, so her guitar was laying around. She had a student model Gibson flattop [acoustic], and I started picking that up. And eventually, in 1961, that was the end of the accordion lessons. I still played for a while, but when I latched onto the guitar, I just drifted away from anything having to do with studying accordion or trying to play it anymore. I still had it – I could still pick it up and play the few things I had practiced enough…I would memorize stuff. We all had pretty good ears as a result of being around my mother and being around all that music. So, I started picking up the guitar and just learning what I could – just toying around with it. But I have a cousin who is in the age range of ten or eleven years older than me, so he would’ve been in Vini Poncia’s and all of those guys’ orbit. And he was playing professionally.

Rick: What was his name?

Frank: Jimmy Gagliardi. And his father could actually play chord-melody guitar. He’d come over and pick up my sister’s guitar, and for some God knows what reason, he could play things like “Sweet Sue,” and play these little chord-melody arrangements. And he played the same exact introduction on every song which was… [strums chord-melody intro on the guitar].

Rick & Allen: [laughter]

Frank: Yeah, that was the way every tune started, no matter what it was going to be.

Rick: Do you remember Jimmy’s father’s name?

Frank: Frank – my uncle Frank. Well, Jimmy – when he was in Rhode Island – used to play at – ‘cause I just looked this up – remember the Club Homestead?

Rick: Yeah.

Frank: Right behind Axlerod’s? It was a dump! I mean, it was a dive bar. He used to play there when I was transitioning to guitar and picking stuff up. He would come over to the house, and he saw me playing the guitar. He got a kick out of that I was trying to play, whatever it was, and he used to show me stuff like Bill Doggett tunes [Jazz and R&B keyboardist and bandleader of “Honky Tonk” fame] and other R&B stuff on the guitar. That was the beginning of my trying to play music that was guitar-centric, like Duane Eddy; you know, “Forty Miles of Bad Road,” “Rebel Rouser,” stuff like that. That’s what got me interested in playing that style of guitar. And from there I eventually took some lessons, but it wasn’t for quite a while. I played for a number of years just playing whatever I could pick up on my own, so it wasn’t as much as a thing as the accordion had been as far as study, but then I did take some lessons from Peter Tutalo. He had a studio, and somebody – I think my sister’s boyfriend – knew him and I took some guitar lessons from – I’m pretty sure – John Vastano. I think I took some, but not a lot of lessons from him. It’s kind of hard to piece together the years here. I was, I don’t know, twelve, thirteen, fourteen during this time.

Ed. Johnny Vastano went on to become lead vocalist and guitarist for The Blue Jays, one of Rhode Island’s most popular bands in the 1960s which relocated to L.A. and recorded as White Water for RCA. He finished out his career as a successful songwriter and session guitarist on the L.A. scene.

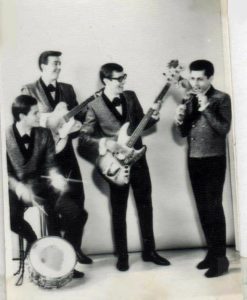

Frank’s cousin Jimmy Gagliardi (seen here at right) in the 1950s with one of his early bands. Frank credits Jimmy with moving him forward on the guitar and introducing him to R&B music.

Rick: So, you were playing blues-based and R&B-based music, not jazz at all yet…

Frank: Oh no.

Rick: …and it sounds like it’s pre-Beatles, really, that you were getting into the guitar, which was unusual for musicians your age.

Frank: Yes. Eventually I wound up with Tony Evangelista. He was the guy who started mentioning people like George Benson to me. I still have the notebooks. He taught chord melodies on [tunes] like “Misty” and bossa nova [style] [Antonio Carlos] Jobim stuff. Eventually I had enough under my belt as far as chord forms and whatever. He had a whole system of showing you the chords, and he wrote them all out by hand in these notebooks. He even drew the chord diagrams; the [guitar] fingerboard diagrams. It was an arduous thing how he used to teach you. But I remember going to play at an event with [guitarist] Billy Marrocco. That was the first band I was in. Do you know Billy?

Rick: Oh, yeah.

Frank. Alright. So, Billy started a band, and I went over to his house on Federal Hill with my small amp and my Kay guitar. We had this band that didn’t have a bass player.

Rick: To backtrack just a second there, so we don’t forget, you have now gone from your sister’s acoustic to the Kay electric.

Frank: Yes.

Rick: How did you get the electric?

Frank: I asked for it for Christmas. With my folks, whatever you asked for in the way of a musical instrument for Christmas – you were probably going to get it. [Frank brings out a single pickup Kay guitar.] This is not the original one. This was sent to me a couple of months ago by my brother Jery who has a business called Rhode Island Guitar Trader. For years, he kept saying, “I see these Kays [like you had]. Should I buy one?” because it was my guitar until I got a better one, in which case he was then given the Kay.

Rick: So, by the time you were doing things with your cousin Jimmy and then later Johnny and Peter [Vastano and Tutalo] you had an electric guitar.

Frank: Yes.

Rick: We’re in 1963, maybe ’64…

Frank: ’63, ’64, ‘65.

Rick: You were already playing guitar before the Beatles though, which is a very important point for musicians your age, because most [guitarists] started after the Beatles.

Frank: Yes. And again, it was more because of Duane Eddy and “Guitar Boogie Shuffle,” things like that which featured electric guitar in some kind of instrumental recording in popular music.

Ed. The instrumental “Guitar Boogie Shuffle” by The Virtues which reached #5 in Billboard in 1959 was a Rock ’n’ Roll update of Arthur Smith’s 1948 #8 Country & Western hit “Guitar Boogie.”

Allen: And you were on your way to your friend’s [house] with a little amp and a Kay guitar on Federal Hill…

Frank: Yeah, yeah. My father had to drive me over. So, I wasn’t sixteen yet in the beginning of it, but eventually – ‘cause I remember driving over there eventually; oh no, maybe not. I think that was all before I was sixteen or old enough to drive. I got my learner’s permit on my birthday, and I drove as soon as I possibly could and went out and got a job and bought a car and got on the road. But yeah, the Kay guitar went to Jery. He painted it red and took it apart and it wound up in the trash which is why he always felt as though he should provide me a replacement. My folks had gotten me a [Fender] Jazzmaster from Ray Mullin Music [then in Pawtucket and still operating in 2022 in Swansea, Massachusetts] somewhere in the 1964 range. I wish I still had it. I sold it here [in California]. We all have those stories.

Rick: So, picking it up here, everything sounds pretty casual up to Mr. Evangelista. Did you study with him for a long period of time?

Frank: I think it was a long period of time, but I’d be lying if I say I remember the years.

Rick: That was the first jazz for you on the guitar really.

Frank: Yeah. But we weren’t calling it “jazz;” we were just calling it playing music that was more harmonically sophisticated, maybe, than just a I-IV-V blues or R&B kind of stuff.

Allen: And what was the name of the ensemble that you were in? You started a story about going over to Federal Hill…

Frank: It was a band called The Tumbleweeds.

Allen: That was the first band?

Frank: Yeah. It was Billy Marrocco and me, and Joe Silva played drums, and we didn’t have a bass player. For a while, we had an organist whose name escapes me – he lived on Chalkstone Avenue in Providence. Then something happened and the whole thing fell apart – he wasn’t part of it anymore. We had a bass player for a couple of rehearsals that we had to drive all the way out to Warwick to pick up because he didn’t have transportation. And we played a few gigs here and here. We played the Rhode Island Junior Miss pageant at Rocky Point. We played at Arnold Palmer’s putting course in Cranston, you know, a few little things like that. We played at a battle of the bands at some school right in Olneyville [Oliver Hazard Perry Junior High] and someone from a rival band pulled the power plug on us in the middle of our set. Typical…

Rick & Allen: [laughter]

Rick: Where did you go to high school?

Frank: I went to Mt Pleasant High School, but first I went to Nathanael Greene Junior High for ninth grade because high school then was just for [years] ten, eleven and twelve. That was the time where I was just listening to music and was probably taking lessons with Tony [Evangelista]. I remember getting together with Billy [Marrocco] a long time after The Tumbleweeds, somewhere in North Providence. As we were warming up with a bossa nova or something, he looked at me and said “Wow, you really learned a lot since last time I played with you.” It was the result of all the stuff I had learned from Tony.

Rick: So, during high school, you were primarily just playing by yourself and studying, not playing in any of the teenage bands or anything…

Frank: Yeah. I would go see the bands that would play at the high schools: The Driftwoods, Butch Giachelli had a band called The Why Nots I think.

Rick: So, you were not participating as much as [networking and observing.]

Frank: Right. I was just practicing and working on stuff and listening to music. By that time, it was getting closer to when our generation [the baby-boom generation] made the transition from AM to FM radio, and you were listening to WBRU eventually…like closer to ’68. ’67; ’68, even ’66. So that was a whole other direction. By then you had The Grateful Dead; you had Eric Clapton and Cream and all of those people. That’s what I was listening to really. I wasn’t listening to George Benson. We were all listening to those guys, the guitar hero guys of the sixties. So, I was kind of stuck in limbo where I had [played] “Misty” and bossa novas, and these guys were doing what they were doing, and there was this chasm as far as a difference in style and equipment and all of that stuff.

Rick: I remember, when I was first introduced to you, that there was a big [interest] – maybe it had already passed or just become part of what you did – but I knew you loved Jimi Hendrix at that time.

Frank: Yeah. I mean, the wallpaper on my phone is Jimi Hendrix at the Rhode Island Auditorium.

Rick & Al: [laughter]

Rick: Alright, so now we’re ready for college. Did you go directly to Berklee?

Frank: You probably can’t see this, but… [shows photo of Hendrix at the RI Auditorium]

Al: Wow!

Rick: I’ve seen those on Facebook that your brother Joe put up.

Frank: Yes, he took them. But at that point, [as far as] Jimi Hendrix goes, he was playing his style and the volume and all and I wasn’t doing that. I wasn’t trying to play that. If anything, I was listening to Eric Clapton and more “clean stuff,” or more blues-oriented stuff, or Jerry Garcia’s more clean sounding extended twenty-minute solo pentatonic stuff; that was the stuff that I was trying to play at that point. So, I still wasn’t trying to play bebop or swing or anything like that.

Rick: So, from Mt. Pleasant directly to Berklee?

Frank: Yes.

BOSTON BLOW-UP!

THE BERKLEE YEARS

Frank: [Berklee] was the only school I applied to. I was accepted. I went for four years, and I got a degree, and I left. I couldn’t imagine what else I might do after high school other than go to music school. So, I’m pretty sure Tony Evangelista wrote my letter of recommendation for Berklee. I can’t really remember any of those details, but…

Rick: You would’ve had to audition, and then obviously you got accepted.

Frank: Yeah.

Rick: And there was no ed[ucation] degree or anything at Berklee at that point, right?

Frank: Yes, there was!

Rick: Oh, there was?

Frank: Yeah. I majored in Music Education. I was advised not to [do so] by the dean. In the entrance interview, the dean said, “You probably don’t want to go into education because you’re so youthful looking that, even by the time you get out, you’ll look as young as your students, and you’ll have a hard time controlling them.” And I thought, well I don’t know if I buy that!

Rick: When you got to Berklee, you were assigned an applied teacher, right?

Frank: Yes – Mick Goodrick.

Rick: Oh boy! Wow!

Frank: He pretty much reduced me to tears in the placement session.

Rick: [laughter]

Frank: It was like, “I can’t play this! I can’t do this.” “Read this. Here, play this.” But he was notorious for just putting you through the wringer. We actually became good friends. I studied with him for three years, and he did some really nice things for me – lent me a nylon string guitar for a whole semester. We were friends after that. I used to go up and take lessons and hang out in Boston and Cambridge, different places where he lived, and we remained friendly for quite a long time. He was a good guy. He just had that mean streak where, if he wanted to mess with you, he could mess with you in spades.

Rick: He must have been a major influence then; not just for being a taskmaster, but on what became your style and direction.

Frank: Yeah. He played a lot of fingerstyle as well as picked stuff, and so that influenced me a lot.

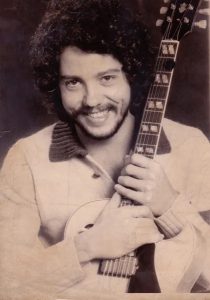

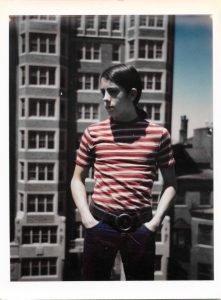

Frank on the roof of his apartment building in Boston, Massachusetts circa 1970 during his time at the Berklee College of Music

Allen: And would you say that’s what changed your listening habits a little bit?

Frank: Well yeah, because, at Berklee, they had a listening list where you were supposed to be listening to all these different people. They had a library on the top floor of the Boylston Street building, and you were supposed to go up there and listen to all these different recordings. They were mostly on vinyl in those days. You would listen to Big Bands and all that stuff, and a lot of the stuff didn’t interest me at all; even somebody like Herbie Hancock. I thought, there’s no guitar in there, and I’m not interested in this. There was a lot of it that just didn’t suck me in. George Benson [jazz guitarist who began his career with organist Brother Jack McDuff’s R&B-infused jazz-funk quartet] was kind of the gateway guy for me. He had enough of a bluesy “something” going that I could connect with. I told this story in that documentary [A Not So Average Joe] on making my Joe Pass [tribute] album [For Joe]. I was in an ensemble, and there were two guitarists, and there were supposed to be three horns, and half the time the horns didn’t show up. So, we wound up having to play the melodies and play solos. The guy that ran the ensemble was a saxophone player, and he tried to get us to phrase like horn players. And he’d say, “These gotta be legato phrases and you gotta do this, and you gotta do that. This is how you play the melody. You gotta listen to horn players, and you gotta learn to play like horn players, like Herb Ellis or Joe Pass.” Right. “Joe Pass…” Turning to the other guitar player, I’m looking at him as if to say, “Who the hell is Joe Pass?”

Rick & Allen: [laughter]

Frank: And so, not too long after that, I went to Strawberry’s record store, and I saw the Joe Pass section. I picked out an album just to hear what he sounded like, and came home and put it on, and it was, “Oh, my God!” The album was Intercontinental.

Rick: A major record. On MPS Records.

Frank: Yes. He had told me this story years ago himself, ‘cause I talked to him a lot about that album. But one of my grad students just wrote me and said he’s reading Eberhard Weber’s autobiography. Eberhard is the bass player on Intercontinental. And Eberhard said they were there, and Joe was touring with Art Van Damme, the accordionist. They were there doing this record date. Everything they did was pretty much first takes so when they got done with the record, there was all this time left. One of the producers, Joaquim Berendt, asked Joe, “Do you wanna do a trio album with bass and drums”? And so, they got Kenny Clare, and they did the [Joe Pass] trio album in the spare time that they had left over from what had been booked for the Art Van Damme album. And again, Eberhard said it was pretty much all first takes.

Rick: Wow.

Frank: And when you listen to that album, the arrangements are pretty sophisticated. It’s a very high level. It’s still one of my favorite guitar trio albums. And it was recorded live!

Rick: Let’s backtrack – you’re in Berklee studying with Mick and you’re in the Ed degree program.

Frank: It was not too long before that, that they actually became a college. Because I think the first year or two that I was there it was “Berklee School of Music.”

Rick: Right. That’s the transition period.

Frank: And then in 1970 it became Berklee College of Music.

Rick: That degree allowed you to teach in a public school if you had so chosen.

Frank: Yes. You’d get a certificate. I mean, I knew damn well that was nothing I’d wanted to do from when we had to do the practicum observation stuff in junior year. I went to a junior high school, and here’s all the junior high school kids acting like the jerk that I was in junior high school. [I thought], “Yeah, I’m not getting in this line.”

Rick: Were you gigging while you were in college? You were living in Boston; you weren’t commuting.

Frank: I tried to commute for the first month, but it was hell, and I wound up living there. So, I lived there for three years, but I wasn’t gigging. I wasn’t playing anything.

Rick: You were just going to school.

Frank: I was just trying to get through school, and I was working part-time. I was coming home on the weekends and was working in a sneaker factory just to have money. It was Nohel Manufacturing. They made women’s and children’s sneakers. It was on Niantic Avenue in Cranston. I was vulcanizing sneakers, melting the bottoms onto sneakers. It was something I had done part-time after high school, and then full-time during the summer from the time I was sixteen because I needed a job; ‘cause I needed a car.

Rick: I will just interject that you had a very unusual path compared to other musicians in your age group and of your caliber.

Frank: Yeah…and so, I was just trying to get through school, and I wasn’t really doing any professional playing. And then finally, in ’71, I auditioned for and got into the Stovall Brown Blues Band [led by Chris Brown of Warwick] and that was when I started playing professionally.

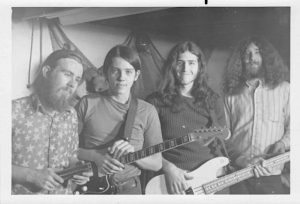

The Stovall Brown Blues Band 1971: Chris “Stovall” Brown, Frank Potenza, Warren “Snip” Potter & Tom Goodrich

Rick: So, this is after graduation?

Frank: Before.

Rick: I was going to ask what happened in fourth year which was different than the previous three years? You started playing with Stovall…

Frank: Yeah, but it was towards the end of that if I’m not mistaken; towards the middle to the end. I was just barely starting to play professionally by the time I graduated in ’72.

Rick: So, you more-or-less did not gig all the way through college, and towards the end you got into the Stovall Brown band.

Frank: Yeah, just for very last piece of it. There’s a photograph of me playing at a music festival in Lincoln Woods [a state park in northern Rhode Island] the day after I graduated from Berklee.

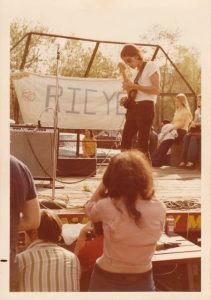

Frank Potenza and his Fender Jazzmaster on stage at Rhode Island’s Lincoln Woods State Park in 1972 the day after he graduated from college

Rick: Who was in the band when you first started?

Frank: Oh, man…it was me and Chris, Snip Potter on bass, Tom Goodrich on drums.

Rick: How long did you stay with Stovall Brown?

Frank: It was on and off for a couple of years, ‘cause the band changed and then it was me and Rob Nelson on guitars, Larr Andersan and then Bob Dexter played drums, and Bill Bradshaw played bass.

Rick: He used to be in the Young Adults [2016 inductees].

Frank: Yeah. Then there was somebody else there for a while before that, but there was that iteration…

Rick: Oh, was it Tom Reed?

Frank: Tom Reed! Tom Reed was the bass player in one of those bands.

Rick: Yes. Sugar Bee.

Frank: Yes. Exactly. Good memory. How’d you come up with that? I would have never come up with that.

Rick: [laughter] Don’t ask me. I can’t remember anything except for music. [laughter] That’s very important stuff, though. Ok, so you’re with Stovall Brown for a couple of years. Is that how you earned your living, playing music?

Frank: Yes. Well, the combination of that, and I started teaching at one of the iterations of the Rhode Island School of Music on Branch Avenue.

Rick: That school came up quite a bit during the induction of Artie Cabral. He was a founder with Hal Crook…

Frank: Yes.

Rick: …and you were probably one of the first teachers to come on board.

Frank: I don’t know if that’s the fact. I might have been the first guitar teacher to come on board, but this was when it was at the mill location on Branch Avenue which is less than a mile from where I grew up, from my mother’s house. So, I was teaching part-time there. So, just whatever I could do to scrape together an income.

Members of the faculty at the Rhode Island School of Performing Music in Providence, Rhode Island mid-1970s: Frank Potenza, Hal Crook, Artie Cabral, Fred DeChristofaro & Greg Wardson

Rick: Just for a little geographic side thing I’d like to have [for readers] for reference: that’s the same mill building near Route 146 on Branch Ave where Mark Campellone had his shop later.

Frank: Exactly. My mother had worked in that mill as a younger person, and there are a lot of those mills in that section of Wanskuck. That’s what the town was: the mills and then the houses that were set up for the people who were management and the other people who worked there lived in the tenement houses.

Rick: So, you graduated in ’72, correct?

Frank: Yeah.

Rick: Between ’72 and ’74 you were primarily gigging, and you had begun teaching. Were you teaching privately as well, or just at the school?

Frank: Yeah. Anything I could scrape together. I taught ear training classes and private lessons and ensemble.

Rick: We’re getting into the time where you would be more or less playing jazz?

Frank: All of this time, I’m trying to become more able to play the style of jazz that I was seeing people play at [Providence jazz club] Allary and clubs like that; Mike Renzi’s [2018 inductee] trio. This was about ’74. You get that far, and now I’m chasing that [jazz playing] a lot harder than I was. But at that same time, I’m playing in show bands, playing top 40 music, doing something I don’t really want to be doing.

Rick: What were you doing in the line of show bands. Any names?

Frank: The first one after Stovall Brown was called Brotherhood. Then Brotherhood split up into different factions.

Rick What was after that?

Frank: Family Tree. Some of us wound up becoming the six-piece band behind Family Tree [radio personality Gary DeGraide and three members of the musical LaChance family].

As Frank notes above, by 1974 his career was clearly headed in a jazz direction. That year, he met Joe Pass when he took his father to a performance at the famed Jazz Workshop in Boston. After the show, he went to Joe’s dressing room to introduce himself and to ask if Joe would be giving any lessons while in Boston. Joe said yes and told Frank to come by his hotel the next day. He had his first lesson that day which proved to be the start of a twenty-year friendship which lasted until Joe passed away in 1994.

Frank began his jazz career in the 1970s. He is seen here performing at Allary in Providence with Matt Cornish on trumpet

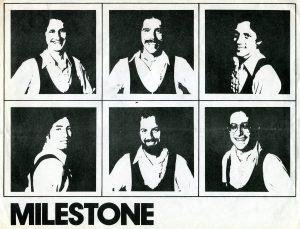

In addition to the general business and show band gigs which sustained him financially during this period, he began working with multi-instrumentalist Diamond Centofanti and his wife, vocalist Pat Loncar, in their jazz group Diamond and he was a member of another band with jazz leanings, Milestone. The group included pianist Mike Martino, bassist Scott Albers, Stanley Johnson on trumpet, Billy Andrews on drums [2013 RIMHOF inductee] and saxophonist Dan Moretti [Class of 2017]. Frank began frequenting and performing at Allary, a jazz club in downtown Providence which was the center of the Rhode Island jazz scene in the 1970s.

Milestone poster: (top row) Stanley Johnson, Dan Moretti, Frank Potenza, (bottom row) Michael Martino, Scott Albers, Billy Andrews

OPEN UP THAT GOLDEN GATE

In 1980, Frank moved to Los Angeles. He began to make a name for himself on the L.A. jazz scene and in 1981 he landed a position as an adjunct instructor in the Commercial Music Program at Long Beach City College directed by trumpeter/composer George Shaw. He remained at LBCC until 1995. Frank also began playing with another Rhode Island transplant, saxophonist Scot Scheer who along with Shaw introduced Frank into the L.A. recording scene setting the stage for Frank’s solo career on the label for which they both recorded, TBA Records.

Rick: In the mid-1990s, you made the switch from Long Beach Community College to the Flora L. Thornton School of Music at the University of Southern California.

Frank: Yes. That was ’95.

Ed. While at USC, Frank completed his Masters in Music in 2000 and was promoted to full professor. In 2006, he became the chair of the Studio/Jazz Guitar Department, a position he held until he stepped down in 2018. He published two guitar instructional books in partnership with fellow USC Thornton guitar faculty member Nick Stoubis: Fretboard Mastery – Scales & Arpeggios Book One in 2010 and a second volume in 2012 (USC School of Music Press/Mel Bay Publications, Inc.).

Rick: What kind of gigging were you doing between starting at Long Beach and getting the position at USC?

Frank: Long Beach was like the Scheer Music time [saxophonist Scot Scheer’s group] and we did a record in something like 1980 – geez, I can’t even remember the years of some of these things – but in the early ‘80s we did a record for that label TBA. [The album appeared on the Palo Alto Jazz label, a subsidiary of TBA Records in 1982.]

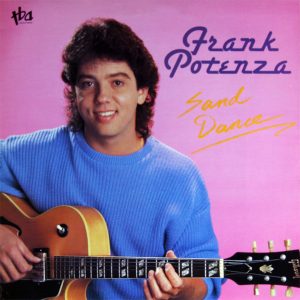

Rick: Are you talking about Sand Dance [Frank’s first album as a leader]?

Frank: No, no. This is one of Scot’s records. I’m gonna say maybe ’82, ’83…yeah, I think the album was called Rappin’ It Up. And there’s another one, the second album that I can’t remember the name of that I played on as well.

Ed. The second album Frank recorded with his friend Scot Scheer and his group Scheer Music was High Rise in 1984 on TBA Records which was co-produced by bass guitar legend Larry Graham of Sly & The Family Stone and Graham Central Station and featured former 5th Dimension vocalist Billy Davis.

And so, that label was eventually the label that I was on with George Shaw. But George Shaw had started doing stuff for them, somewhere around ’84, as a producer, and he asked me to play on his record. It was called Flight 2201 and the band was called Century 22 featuring George Shaw. He asked me to play on that on spec and if it got picked up, he was gonna spin me off a solo deal, which he did. It got picked up by TBA Records and that’s how I started making those records [as a leader] in something like ’85, ’86.

Rick: The first release Sand Dance was ’86, so probably recorded in ’85?

Frank: Yeah.

Rick: Leading up to that, I know you were doing certain jazz things [including touring with saxophonist Ronnie Laws in 1984 and 1985] and things with Scot [Scheer – see above]. Were you doing general business or any…

Frank: Oh yeah – tons, because I played bass as well. One of the things I started doing before I left Providence – this was probably three or four years before I left – someone offered me a gig on bass during the dead of winter, like in February when there’s no work and there’s no money. I was living at the Carleton Street house, I remember [a large townhouse in the Mount Pleasant area of Providence being rented by Frank and the other members Milestone, his band at the time], and it was Richie – can’t think of his last name – he worked a lot at The Harbour House Inn in Westerly. Anyway, he had a trio behind him – bass, keyboards, drums – and he sang, and he worked all the time. Greg Wardson [pianist] worked with him a lot [as well as bassist] Mark Campellone. So, his bass player was going out of town, and he was calling all the bass players he knew – and someone said just try guitar players; maybe they play bass. And he called me and asked if played bass, and I said, well, I don’t really play, and then I thought – I have no work, I have no income – so I said sure! We hung up and I thought, geez what did I just do? So, I called my brother, [bassist Joe Potenza] and I borrowed a bass. It was all Top 40 music, current Top 40. He gave me a list of songs and I learned them all and I went, and I made the gig. I played out of my Fender Super Reverb [guitar amp] for an amp.

Rick and Allen: [laughter]…

Frank: And I thought, wow, I can do this. Then Rose Weaver asked me to do a gig and I thought, wow, now I gotta walk bass lines. Can I do this? And I borrowed a different bass of my brother’s – oh no – I borrowed one of Mark Campellone’s basses, I think, the first time. Then I borrowed a [Gibson] EB-O or some kind of different bass of my brother’s and I walked bass lines. I got through Rose Weaver’s gig. And I thought, I can play bass! Eventually I wound up becoming the bass player on Tony Giorgianni’s Jazz Odyssey thing [a big band] on Monday nights at Allary which was really…I mean that was way over my head, but I did it, and I was still playing out of my Super. I eventually bought a bass from Mark Campellone. I still have it. It’s a ‘70s Fender P [Precision] bass. It’s been modified beyond recognition, and that’s the only bass that I still own to this day. And I started doing a lot of casuals, GB [general business], stuff on bass in Rhode Island. Then, when I moved here to L.A., my ace in the hole as far as taking commercial work was, well – I played bass! So, I didn’t have to do so much in the way of playing GB stuff on guitar, which I really didn’t want to be doing. I would say I’d rather play bass. And so, I had a lot of contractors who knew me as a bass player instead of a guitar player.

Rick & Allen: Wow! [laughter]

Frank: So, that kind of gave me a whole other income that I would never have had, and it really amplified my ability to be able to make a living, because I was making it as a bass player as well as a guitar player.

Rick: [Explains that “casuals” is referred to as “GB” in Rhode Island]

Allen: [Explains that the term is used widely beyond Rhode Island]

Rick: Well in Los Angeles or California, it’s referred to as “casuals.”

Frank: Well, that’s because the union calls it a “Casual Engagement.” It’s like a one-off.

Allen: Oh. Not a “Green Sheet” [gig]?

Frank: No. A green sheet is a trust fund gig. “MPTF.” “Music Performance: Trust Fund.” It’s like a subsidy thing, where the union pays you to go play at like a high school or grammar school or something. It could be a rest home; it could be a whatever, just a place to go to play music for people, and you can get away with playing some jazz as long as you don’t go too crazy.

Rick: So now, you’re gigging, doing casuals, some jazz, playing bass on some of the casuals, playing guitar on some casuals too, right?

Frank: Singing.

Allen: Singing?

Frank: Well, as a guitar player, that was the thing with playing guitar and casuals: you were the rock specialist. So, you were the guy they pointed to when they said they need some rock and roll, old time rock and roll, and now you’re gonna have to sing “Old Time Rock and Roll” which is all well and good, except if you’re playing with a 200-year-old accordion player and a hundred-year-old drummer. And you hear [mouths campy intro to a song], and you just think, oh God, somebody shoot me.

Rick: [laughter] But the money was pretty good.

Frank: Well, again, that was why playing bass was okay – that gets me out of that hole.

WEST COASTIN’ & CALIFORNIA DREAMIN’

Rick: Right. So now, we are up to your first release as a leader, Sand Dance. These records did really well.

Frank: At the time, the concept was: Earl Klugh is at the top of the heap, so, if you can do anything like Earl Klugh you’re good – you’re already holding a nylon string guitar, and you’re playing, in some cases, covers of R&B classics. I did a Marvin Gaye tune, or whoever. “Freddie’s Dead” [by Curtis Mayfield]. That’s basically what we were chasing – the smooth jazz thing. I got a lot of criticism from my friends for doing those records when they first came out. They said, “Why are you playing this wimpy music?”

Ed. Frank Potenza became a successful recording artist right out of the box. His first album, Sand Dance, reached #14 on the Billboard Top Jazz Albums chart in 1986. In early 1987, Billboard split the jazz category into two sections: the Top Jazz Albums with 15 entries and the introduction of a new Contemporary Jazz Albums chart with 25 entries. Frank’s sophomore album, Soft & Warm, reached #10 on the new Contemporary chart. His next two releases both hit the Contemporary Jazz Top 25.

Rick: Your recording of these things…were very successful, but they were [also] very much a cut above. I could not listen to a lot of the stuff [smooth jazz, new age] that was happening in jazz at that time, but your records – and not just because I knew you – were a cut above. I felt – this is what it [smooth jazz] could be.

Frank: Have you ever heard Earl Klugh’s solo guitar stuff?

Rick: Yeah. He’s a great player.

Frank: Oh, God! Yeah. He was a really good player. I met him when he was nineteen, touring with George Benson.

Rick: Playing rhythm guitar because Phil Upchurch [rhythm guitarist on many of George Benson’s most successful albums] couldn’t tour with George [due to his other session commitments and his own recording career].

Frank: Yeah.

Rick: Earl Klugh had to do the rhythm guitar parts.

Frank: Yeah.

Rick: There’s a guy [Upchurch] who played both bass and guitar.

Frank: Yeah, yeah. Absolutely.

Rick: I digress. Your albums are very good. Did the criticism sting you?

Frank: It was that people expected that I was gonna be doing what I did with Diamond Centofanti on my own records. And I understand that, and I get that. I mean “Freddie’s Dead” is not exactly “Giant Steps” [John Coltrane] and “Cherokee” [a jazz standard popularized by Charlie Barnet and reimagined by Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie as the Bebop classic “KoKo”]. But this was 1986, and nobody was running up to me and forming lines with contracts for straight-ahead record dates. I wasn’t getting any opportunities that way, and this is an opportunity that I came very close to declining; just saying no, this is not what I do musically. No thank you. But at some point, I just thought any record at all is better than no records, and it was an opportunity that I thought I should take. And I’m not ashamed of the music at all for what it was. It was very ‘80s production values with drum machines and synthesizers, and the stuff was really restrained as far as the solos were concerned. The material was all four-minute songs, four minutes and change. Radio play was the big target there and the intent of the music. And it was commercial. It was commercial from the word go, which is what the reviewer in Guitar Player who gave me a really scathing review wrote: “It was fine mainstream guitar, but these syrupy…”

Rick: …productions.”

Frank: This was my third album.

Rick: “When We’re Alone.”

Frank: Yeah. And the “syrupy synthesizers” and “the straight eighth-note rhythms get in the way.” The last line of the review was “Commercial from the word go,” which couldn’t have been more correct anyway! That’s what it was. We’re not trying to impress people who are here to hear me play “Cherokee” at 500 beats per minute.

Rick: Well, they’re fine records, and established you in – not just the jazz community – but the mainstream of the music business. This was a “viable artist” here. And it was a terrific career move, and [they were] very good records.

Frank: Thank you. Yeah. They were fun. We had a good time doing them and have a lot of good memories from those years in the studio.

Rick: Did they turn into any touring or gigs?

Frank: You know, we did a little bit of stuff here and there, but not touring. We would do one-off dates, but not anywhere near what you might think would have been possible at that time. There just was nothing that we were able to hook-up to the point of where it was like a tour. We’d go up to northern California and do something or whatever, but there was never any big touring that was connected with that, which is something we were never able to hook-up.

Rick: Your job was never in jeopardy. You never had to make the decision – this is going somewhere, but I’d have to quit my job.

Frank: No.

Rick: So, you managed to have stability and stay current.

Frank: We were both teaching at the college. George [Shaw] was the director of the commercial program at City College, where I was teaching in Long Beach. We had stable incomes; especially him, he was full-time. I was just adjunct.

Rick: Well, it turned into a fabulous career, opening doors, leading up to In My Dreams and Legacy and the real jazz records. The [Three Guitars: Live at the Jazz] Bakery I like a lot too. This is where you become a major guy in jazz guitar. But you don’t think of yourself that way. [laughter]

Frank: No, I don’t. You always have a different perspective from the inside out.

Rick: Jazz was not what it was [commercially and sales-wise] by the time you began recording. Even in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, there was a time where Chick Corea’s Return to Forever and Weather Report and the Headhunters with Herbie Hancock were playing at the Providence Civic Center with those groups. I always wondered if that was giving you some incentive or encouragement to aspire to a career in jazz – when you saw how well [bands like] Mahavishnu [Orchestra with John McLaughlin] and Weather Report were doing.

Frank: Yeah, although that was more on the fusion side of things, and I just always seemed to be not going in that direction of whatever that was – the high-powered, overdriven, high-energy fusion kind of stuff was something that I just wasn’t way into.

Rick: Just like when I mentioned Hendrix [as an influence], you said, “No, I’m more Clapton.” So, the Joe Pass album was more important than the Mahavishnu album in the ‘70s.

Frank: Yeah.

Rick: And Clapton more important than Hendrix in [your] early stages.

Frank: Yeah. It kept me from going in that direction of the whole overdrive, distortion, big amps, all that stuff.

Rick: Interesting. [laughter] Again, a lot of your career is unique and personalized for a person of your age. It diverges from what everyone else did…

Frank: Yes.

Rick: …which I fully admire, and you’ve achieved great levels of success…

Frank: Well, thanks.

Rick: …on your own path, so to speak. We’re pretty much up to the fourth or fifth album here. You had continued teaching, begun your recording career, and you were having success with that. But it did not require you to change your way of life or go on the road. You just had nice, successful record releases.

Frank: Yeah. And then, through the ‘90s, I was doing a fair amount of freelancing on bass. So, that was paying well, and between that and the City College adjunct thing, enough of an income that – I mean, again, I wasn’t making any kind of ridiculous money doing any of these things – but it was a living. It was a way to keep doing what I was trying to do and keep moving forward; keep trying to get closer to what I really wanted to do as far as recordings.

Rick: Which you did with In My Dreams, The Legacy, the album with Shelly Berg, recording with Gene Harris and Wilton Felder. This is the real deal.

Ed. Gene Harris had been a successful recording artist starting in the 1950s as pianist and leader of The 3 Sounds, a swinging and funky trio which enjoyed mainstream success as a “soul-jazz” outfit as well as acclaim in the jazz world. They were one of the most successful acts in the history of Blue Note Records. Harris began a successful solo career in the 1970s which continued until his passing in 2000. Wilton Felder was saxophonist for the very successful group The Jazz Crusaders. Their initial run during the 1960s was followed by a name change to The Crusaders and a new fusion direction for another two decades and even greater success in the 1970s and 1980s. In the ’70s, Felder began doubling on electric bass guitar for their recordings and also became a successful solo artist and one of the most in-demand bassists on the L.A. recording scene.

Frank: Gene Harris. That was like ’96. September of ’96, I started working with him. A friend of mine – the bass player’s an old friend of mine – so, the bass player who was playing with Gene Harris – Luther Hughes – he recommended me when Ron Eschete was leaving [the group]. And Gene just hired me! There was no rehearsal. There was no audition. There was nothing! It was just: we’re playing at the Montreal Jazz Festival on such and such a date; here’s an airline ticket; see you there. Luther gave me a little counseling – a lot of counseling – as far as, okay: here are the tunes he likes to do. Gene didn’t have written music. There were a few hand-written sketches of things that Luther had written out for stuff that he gave me, things like “Summertime,” which are things that I knew. And I listened to the recordings, and I listened to how Gene played the stuff, and I did my homework. But the first time I played with him was at a major jazz festival in Montreal. I walked up to him in the hotel, never having met him, and just walked up to him and hugged him and we became instant friends. The next time I saw him was on the bandstand when he counted off the first tune. Nobody said here’s what we’re doing. Here’s what we’re gonna do. Here’s the keys. Here’s the…nothing! He just started playing, and you played with him.

Rick: That’s called “trial by fire” under most circumstances.

Frank: Yup. It was pretty hair raising, but that was who he was. That was how he ran his band. You were basically his appendages, and when he played loud, you played loud. When he played soft, you played soft. And when he made that switch from very loud to very soft, you’d better get ready, or you were going to be hung out to dry which happened to me a few times.

Rick: Did he take you to task?

Frank: No.

Rick: [laughter] Okay!

Frank: There were few times when he said anything to me other than, “Yeah, that was great. I really enjoyed that.” Every once in a while, he’d say something like once, during “This Masquerade,” on the introduction – it’s just that vamp that goes Fm to Bb for however long, it was an open vamp – and on the [Gene Harris] recording the guitarist, Ron Eschete had soloed over the vamp. So, that’s what I do. He’d start the vamp; I’d start soloing. He’d let me go for sixteen bars, 32 whatever, and then he’d start playing the melody, and you knew when it was coming, and you’d stop playing. So, one place that we played, during my solo I just started palm muting. And I’m playing all these [mouths palm muting], really muted little lines. And I see him looking over at me, and I thought, hmm…I wonder if this is going over or not.

We played the whole tune. We played the rest of the concert, and now we’re in the car going back to the hotel and he says “Frank.” I said “What”? He said, “What were you doing during the introduction to ‘This Masquerade’”? And I said “Oh, I was palm muting.” And he said, “That was great. I never heard anybody do that.” And I of course said, “Well I’m the only guy that does that. Nobody else does that.”

Rick & Al: [laughter]

Al: Just invented it!

Frank: “Oh, that’s my own invention.” I thought of that [story] today.

Rick: Is there anything you can tell me about jazz opportunities you had that are, to me, very noteworthy? Mose Allison. You worked with Joe Diorio. Two guitars is always unusual. You worked with Mundell Lowe. I know about Johnny Pisano. I know you made an album with Wilton Felder. There are certain things here that seem very exciting and big time to me on a jazz basis.

Frank: Yeah. There were a bunch of instances like that, some of which came from Dizzy [Gillespie]. So, I got to play with Dizzy because I was on the faculty at City College, and he was coming in. [Program Director] George Shaw would bring in soloists. The first one I went to was Patrice Rushen. They had Dave Baker; they had David Sanborn; and they had Clark Terry; and they would do a concert with these people as their guests. So, when Dizzy was coming, he didn’t want to play with a student rhythm section. He wanted a professional rhythm section. George [Shaw] looked at me and said, “Do you wanna play with Dizzy”? It was like, are you kiddin’?

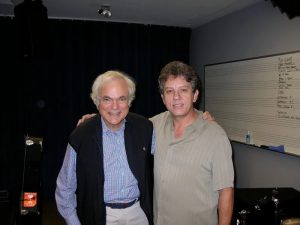

And then when I brought Joe Pass in, he said “You’ll play something with Joe.” That’s when you see those videos of Joe and me playing. It was the one time that we did that. There are places where he’d cut the whole band out, and we’d just play together as a duo and solo and play off of each other. So, a lot of those things happened as a result of just of chance meetings. I’m trying to think of some of the other ones that you were mentioning that just came about.

Rick: Mose Allison.

Frank: Mose Allison happened because I had played with Gene Harris and Paul Kreibich was the drummer with Gene. Mose came into town and he called Paul to play because Paul had played with him before. [The gig] was at the House of Blues and he said he wanted a guitar player. He [Paul] said, “What kind of guitar player,” and he said, “A blues bopper,” and Paul thought of me. So, I played with Mose Allison, but it was one night at House of Blues in Hollywood.

Rick: Mose is special to me.

Frank: Oh, yeah! He was somebody I was aware of and knew of and had respect for, but I didn’t know that much about what he did. And we did actually have some kind of short rehearsal there, so I’d have some kind of idea of what I was gonna do. But it was just – I played a set at the House of Blues.

Rick: I think we’ve hit all the highlights. Is there anything we have not asked you about that you would like to mention?

Frank: What were the rest of the albums that you have listed there that we might have…

Rick: Well, after the TBAs, you start making more straight-ahead jazz things.

Frank: Yes. And that was on Azica Records. So, there was The Legacy…

Rick: In My Dreams. The Legacy.

Frank: The Legacy was basically a tribute to Gene Harris. That’s what The Legacy thing refers to, because it was basically the same bass player and drummer I had toured with when I was with Gene and Larry Fuller played piano. That was what that one was about. And the duo [album] with Shelly Berg [First Takes]. We were on the faculty together at USC. Our offices were right next door, and for years we said we should do something together. And we were going to use a bass player and a drummer. So, we started to play as a duo. I just went over to his office, and we had such a good time playing as a duo, we thought, we don’t need a rhythm section – we’ll just play as a duo.

Rick: Do you know – I’m sure you do – the two albums that Jim Hall and Bill Evans made together?

Frank: Intermodulation and…

Rick: Undercurrent.

Frank: Undercurrent. Yeah.

Rick: Your album with Shelly and those albums – they all go together [for me].

Frank: Oh, thank you. I don’t know that I would say that, but he’s [Shelly Berg] an amazing musician, an amazing player, but I don’t see him anymore. He’s in Florida.

Rick: Oh! That’s the point that I’ve been unable to articulate. If not for Sand Dance, you would probably not have gotten to make First Takes with Shelly years down the road. You know what I’m saying?

Frank: Yeah. And Shelly and I for years had been mutual admirers, but we never even talked about playing together. And then, when I wound up at USC – and then eventually I ended up in an office right next door to him – we were seeing a lot of each other and hearing a lot of each other playing. And one of us said we should do a recital together sometime, and that’s how it got started. That was recorded in a building on the campus that’s no longer there, but we recorded that at USC.

Rick: So, there was no conscious [effort to emulate Evans and Hall], but I can’t think of any other duos – you know there’s famous blues duos like Georgia Tom [Dorsey] and Tampa Red – there’s blues piano-guitar duos, but I can’t think of any other jazz piano-guitar duos besides Jim Hall and Bill Evans. So, it was a fabulous thing to do.

Frank: Thanks.

Rick: This will be something that decades from now people will say, “Well, listen to this. This is a great record.”

Frank: I’m proud of that one. Thank you. And what are others [records] you have listed?

Rick: I already mentioned Wilton Felder. We’re looking at Old New Borrowed & Blue and For Joe.

Frank: Okay. Those are for Capri Records. Tom Burns. He wasn’t too wild about organ. And that’s what Old New Borrowed & Blue is – it’s an organ record. He wasn’t too excited about that, but he let me go ahead and do something that I wanted to do. But he wanted Holly Hofmann to be a guest. Holly, the flute player, is the guest soloist on that. She’s an old friend of mine. She actually was the one who brought me to Capri Records, which is what In My Dreams and the thing with Shelly and The Legacy were on. So, she, again, had turned me on to Capri Records, because she knew Tom from when they were in college, I think. She’s created a lot of really nice opportunities for me, so he wanted her to be the guest, and he let us do that record. And he likes that one, but the For Joe album – I told the story in the documentary there on my website. I was in Colorado playing at this place, and he [Tom Burns] was there, and we were talking about what I wanted to do next. I said I’d like to do something as a tribute to Joe Pass. And when it came around to [it that] I could actually get the same band that Joe had had fifty years earlier with Colin Bailey [drums] and Jim Hughart [bass] and John Pisano [guitar], he said “You know those guys?”

Rick: [laughter]

Frank: I said “Yeah. They’re all friends of mine. I spoke to John about this and I’m sure they’d do it.” And they did! [Now] Colin’s gone – he passed away – Jim’s not playing anymore and Pisano is in his nineties and barely playing anymore.

Rick: Nick of time.

Frank: I feel lucky that I got that done in the nick of time.

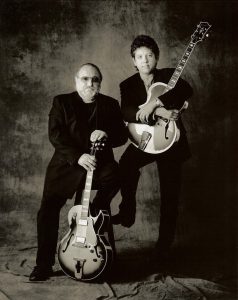

Ed. In September of 2012, Frank Potenza began recording an album which would serve as his homage to his mentor and friend, the legendary jazz guitarist Joe Pass (1929-1994). Taking inspiration from Pass’ 1964 album For Django which served as Joe’s tribute to one of his jazz guitar heroes, Django Reinhardt, Frank assembled the same rhythm section Joe used on that historic album, John Pisano on guitar, Jim Hughart on bass and Colin Bailey on drums, to record the album he called For Joe. He chose three songs from For Django including the title track as well as several other Joe Pass compositions and songs closely associated with his career. Released in 2013, the album was greeted with high praise in the jazz press including a Four Star review in Downbeat. Additionally, the entire proceedings were documented on film by producer-director Dailey Pike. His “jazzumentary” A Not So Average Joe was released in tandem with the album. The film not only gives the viewer a wonderful behind-the-scenes look at the making of For Joe, it’s also augmented by rare and unreleased footage of Joe Pass and Frank Potenza performing together in 1984 at Long Beach City College where Frank was teaching. The film is not currently available on DVD or for streaming at the time of this writing (May 2022), but can be viewed for free on Dailey Pike’s webpage at: https://joepassfilm.wordpress.com/2013/09/

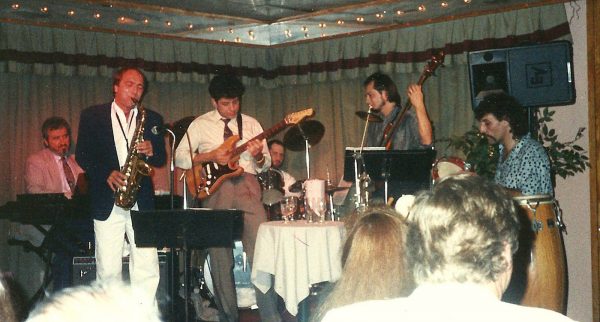

Frank Potenza performing with Johnny Pisano, Jim Hughart and Colin Bailey at the release event in 2013 for his album “For Joe”

Rick: And now that’s quite a long time ago – not even counting COVID – but if that’s your last album, I would think you would be happy with that.

Frank: Yeah.

Rick: But I would love to see you make more albums.

Frank: Yeah. I’m not sure what’s gonna happen. With COVID and everything it’s like, God knows what’s gonna happen. But I feel blessed and fortunate that I’ve done what I’ve done.

Rick: It’s a fabulous legacy…

Al: Yes, it is.

Rick: …and a tribute to Rhode Island, and a great contribution to Rhode Island’s musical heritage.

Frank: Thank you, both, very much for all of what you do. It’s been a pleasure.

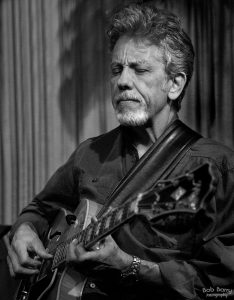

Frank Potenza performing at his induction into the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame in 2017 with Tim Ray on piano, Marty Richards on drums and Frank’s brother Joe Potenza on bass guitar

Unless otherwise noted, all images appear courtesy Frank Potenza and the Potenza family collection

FRANK POTENZA DISCOGRAPHY

AS A LEADER OR CO-LEADER

1986 Frank Potenza – Sand Dance (TBA Records TB-206)

1987 Frank Potenza – Soft & Warm (TBA Recods TB-222)

1987 Frank Potenza – Soft & Warm (TBA Recods TB-222)

1988 Frank Potenza – When We’re Alone (TBA Records TB-235)

1988 Frank Potenza – When We’re Alone (TBA Records TB-235)

1989 Frank Potenza – Express Delivery (TBA Records TB-249)

1989 Frank Potenza – Express Delivery (TBA Records TB-249)

1999 Frank Potenza – In My Dreams (Azica Records AJD-72212)

1999 Frank Potenza – In My Dreams (Azica Records AJD-72212)

2002 Pat Kelley, Frank Potenza & John Stowell – 3 Guitars Live at The Jazz Bakery (CD Baby 602977056921)

2002 Pat Kelley, Frank Potenza & John Stowell – 3 Guitars Live at The Jazz Bakery (CD Baby 602977056921)

2003 The Frank Potenza Quartet – The Legacy (Azica Records AJD-72222)

2003 The Frank Potenza Quartet – The Legacy (Azica Records AJD-72222)

2005 Shelly Berg & Frank Potenza – First Takes (Azica Records ADJ-72233)

2005 Shelly Berg & Frank Potenza – First Takes (Azica Records ADJ-72233)

2009 The Frank Potenza Trio with special guest Holly Hofmann – Old, New, Borrowed & Blue (Capri Records R-74093)

2009 The Frank Potenza Trio with special guest Holly Hofmann – Old, New, Borrowed & Blue (Capri Records R-74093)

2013 Frank Potenza – For Joe (Capri Records 74127)

2013 Frank Potenza – For Joe (Capri Records 74127)

2019 Frank Potenza – A Guitar For Christmas Vol. 1 (Frank Potenza Music EP Download)

2019 Frank Potenza – A Guitar For Christmas Vol. 1 (Frank Potenza Music EP Download) AS A SIDEMAN

AS A SIDEMAN

1982 Scheer Music – Rappin’ It Up (Palo Alto Jazz PA-8025) 1984 Scheer Music – High Rise (TBA Records TB-204)

1984 Scheer Music – High Rise (TBA Records TB-204)

1985 Century 22 featuring George Shaw – Flight 2201 (TBA Records TB-209)

1985 Century 22 featuring George Shaw – Flight 2201 (TBA Records TB-209)

1987 Wilton Felder – Love Is A Rush (MCA Records MCA-42096)

1987 Wilton Felder – Love Is A Rush (MCA Records MCA-42096)

1999 Gene Harris – Alley Cats Live at The Jazz Alley (Concord Jazz CCD-4859)

1999 Gene Harris – Alley Cats Live at The Jazz Alley (Concord Jazz CCD-4859)

In addition to the above recordings, Frank Potenza’s catalog also includes appearances on albums by a host of other artists including

In addition to the above recordings, Frank Potenza’s catalog also includes appearances on albums by a host of other artists including

Damon Rentie, Daline (Jones), Tim Heintz, Paul Russo, Sunny Wilkinson and Bobby Pierce.

A FRANK POTENZA SCRAPBOOK

Frank through the years with family, friends and heroes

At the Dizzy Gillespie rehearsal for the LBCC concert in 1984: George Shaw, Frank, Sherman Ferguson, Dizzy and Leroy Vinnegar

Frank Pontenza on stage with friends during one of his frequent returns to the east coast: Diamond Centofanti, Greg Abate, Frank, Mike Zanghi, Joe Potenza & John LaMoia

LINKS AND RESOURCES

FRANK POTENZA OFFICIAL WEBSITE

https://frankpotenza.com/home

FRANK POTENZA FACEBOOK PAGE

https://www.facebook.com/frankpotenzajazzguitar/

FRANK POTENZA INDUCTION INTO RIMHOF DOCUMENTARY SHORT

Produced and Directed by Norm Grant and Dr. Tom Shaker, Pete & Buster Films (2017)