Eileen Farrell

2012 INDUCTEE

Classical

EILEEN FARRELL: THE SONGBIRD OF MANVILLE ROAD

by Gerard Heroux

A singer’s voice is the most distinctive of musical instruments and it’s as personally identifiable for the singer as a face or body shape is for an actor. And like the actor who specializes in certain types of characters, it’s not uncommon for a singer to play to his or her natural strengths and specialize in certain types of music. Some singers even specialize in the music of a particular composer if it suits their voice. But this was not the path Eileen Farrell (1920-2002) chose to follow. In fact almost from the beginning, this great American dramatic soprano, who took her first serious steps toward a career in music while still living at her family home on 239 Manville Road in Woonsocket, RI, was markedly adept at singing both in the European operatic style and in the more informal style of American popular music.

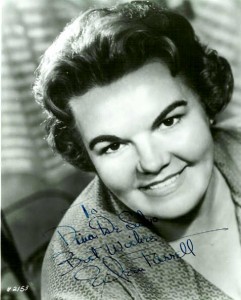

Variety was the hallmark of Eileen’s career right from the start. She sang in many different types of venues – from pre-recorded radio and television shows (running the gamut from concert presentations to sketch comedy), to church services, to live performances in the great music halls of the world – in musical settings ranging from song recitals with solo piano accompaniment to oratorios and operas with full symphony orchestras. From her very first professional job in New York, singing on the radio as part of the studio chorus at the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), Eileen sang regularly with some of the best musicians in the world, and this professional relationship continued in short order on her weekly CBS program Eileen Farrell Sings (1941-1947) and on the albums she recorded throughout her long career from the mid 1940s to the mid 1990s.

She was the go-to soprano for many of the great orchestral conductors during the 1950s and 60s, recording and concertizing with Arturo Toscanini, Pierre Monteux, Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy, Maurice Abravenal, and most frequently Leonard Bernstein, to name just a few. Eileen is said to hold the record as the soloist who has performed the most with the New York Philharmonic, largely due to the two weeks of four daily performances she gave with the orchestra during the intermissions for the Tyrone Power film, “The Black Rose.” This was part of an experimental community outreach by the Philharmonic for the moviegoers at the Roxy Theater, Manhattan, during the month of September 1950. The program consisted of some short instrumental selections and Eileen singing a classical aria and the old Irish tune, “The Last Rose of Summer” accompanied by the orchestra’s harpist.

She was the go-to soprano for many of the great orchestral conductors during the 1950s and 60s, recording and concertizing with Arturo Toscanini, Pierre Monteux, Leopold Stokowski, Eugene Ormandy, Maurice Abravenal, and most frequently Leonard Bernstein, to name just a few. Eileen is said to hold the record as the soloist who has performed the most with the New York Philharmonic, largely due to the two weeks of four daily performances she gave with the orchestra during the intermissions for the Tyrone Power film, “The Black Rose.” This was part of an experimental community outreach by the Philharmonic for the moviegoers at the Roxy Theater, Manhattan, during the month of September 1950. The program consisted of some short instrumental selections and Eileen singing a classical aria and the old Irish tune, “The Last Rose of Summer” accompanied by the orchestra’s harpist.

Even within her classical repertoire Eileen sang many different types of operatic roles, most of which showcased her powerful voice and noble stage presence. She also developed an affinity for the music of the early 18th century Baroque masters, such as Johann Sebastian Bach and George Frederick Handel. This music requires a flexibility and lightness of tone not usually associated with dramatic sopranos. Yet she successfully adapted her voice to this earlier historical style of music as a member of William Scheide’s Bach Aria Group, one of the first professional musical ensembles in the United States dedicated to authentic presentations of Baroque music. Amazingly, Eileen toured and recorded with this group throughout much of the 1950s and early 1960s, concurrent with her moves into full operatic productions, the most spectacular being her five seasons as one of the leading sopranos of the New York Metropolitan Opera from 1960-1966.

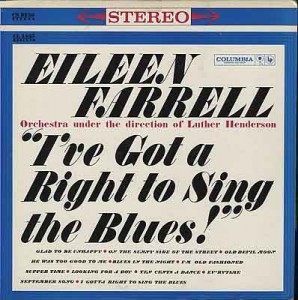

And as if her career wasn’t varied enough, Eileen famously filled in for an ailing Louis Armstrong, singing “On the Sunny Side of the Street” with Armstrong’s All-Stars on an Ed Sullivan TV show taped at the 1959 Spoleto Festival, Italy, in which she coincidentally happened to be performing a classical program. It was this performance which sparked the creation of her first album of American popular songs, “I’ve Got a Right to Sing the Blues” on the Columbia record label (arrangements by Luther Henderson, who worked with Eileen on several subsequent LPs).

Family Background

What was the source of this nimbleness of voice and attitude? Well, just one look at the lives of her parents, Michael Farrell and Catherine “Kitty” Kennedy Farrell, and the answer becomes obvious. To start with, they were both musical performers themselves, who adapted to changing circumstances and hard times by working a variety of jobs, both music and non-music related, in their early lives and later on as a married couple. This strong work ethic allowed them to support a large family through the Great Depression, with Kitty in particular proving especially flexible and adaptive in the face of her husband’s alcoholism.

Eileen claimed her father was a binge drinker, able to go for long periods in sobriety before suddenly going off on a two-week bender. This must have called on special reserves of fortitude and “playing it by ear” from both mother and children, never knowing when their family life would get up-ended. Eileen also claimed that her father was exposed to alcohol at a young age. Starting as a young boy in Newfoundland, Canada, Michael was performing professionally as a singer and whistler known as “The Irish Songbird” and it was not uncommon for older performers to give drinks to the young lad to make him “sing better.” It was probably a miracle that Eileen’s father survived into manhood, but survive he did, and he was by all accounts handsome, gregarious and well dressed.

Michael Farrell was probably looking for a stable partner in more ways than one when he met Kitty Kennedy in her hometown of Woonsocket. They were married shortly after in 1909 and together they spent the first year or so of their married life as “The Singing O’Farrell’s” performing everything from Mozart to traditional Irish songs on the East Coast vaudeville circuit. However, the Farrells were out of show business well before 1920, the year Eileen was born – the last of their four children – in Willimantic, CT. Yet Kitty and Michael managed to keep working, in one way or another, at various music and theatre related jobs while raising their children. Most notable of these were Michael’s time as an instructor of dramatics at the Storrs Agricultural College (now the University of Connecticut) where Kitty also worked as director of the girl’s glee club, and Kitty’s time as the church organist and choir director at St. Mary’s Roman Catholic Church, Norwich, CT. Michael also did odd jobs and some house painting. Eventually he became known as a gold leaf specialist, decorating the ornate interiors of movie palaces, with his crowning achievement being New York’s Paramount Theater on Broadway at Times Square.

Interior of Paramount Theater, Times Square, 1929 (Demolished and converted to office space in 1967)

Eileen’s parents were the main musical influence on her as she grew up. Kitty, a talented coloratura soprano, taught all her children voice and piano, while Michael sang for family and friends at home and in church. He also played saxophone, guitar, banjo and mandolin. In fact it was her father’s high baritone that Eileen credits as inspiring her to becoming a singer. He had a voice that was, in her recollection, “beautiful, strong and a little sad, He sang straight from the heart, and the minute he opened his mouth, his voice took a hold of me, and I would start to cry.”

The Farrell siblings: Eileen, John and Leona (A third sister, Gertrude, died just shy of her 2nd birthday many years previous)

The other influence on Eileen was her older sister, Leona, who was also a talented singer but who unfortunately suffered a painful paralysis due to an infection when she was 15 years old and couldn’t walk without assistance for the rest of her life. It was Leona who loved to listen to the Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts of the 1930s (young Eileen preferred the movie music of the day). So it was through her sister that Eileen became familiar with the music of the great operas and the sound of great opera singing. By her own admission, it was through Leona that Eileen Farrell learned what it meant to persevere and overcome adversity.

School Years and Early Career

Eileen began singing in earnest while the family lived in Norwich, CT. She assisted her mother in the church choir and sang as a soloist at funeral services. Later in 1936, when she was about to start her sophomore year in high school Eileen’s family moved into the house of her recently deceased maternal grandfather at 239 Manville Road. She enrolled at Woonsocket High School where she sang regularly with the school band. During her senior year she played the role of Buttercup in the school production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s H.M.S. Pinafore and then she won a statewide award for being the best vocalist at the spring band festival.

Yet other than her interest in music, Eileen was, by her own admission, an indifferent student and she had no clear direction after graduation. But she accepted her mother’s offer of a trip to Manhattan, the main purpose of which was for Eileen to meet Merle Alcock, someone Kitty Farrell knew from childhood summers in Hyannis, MA when they both studied with the same music teacher. Kitty saw Alcock’s advertisement offering voice lessons in the New York Times and she thought it was worth a try to see if her daughter had what it took to make a life for herself in music. Alcock accepted Eileen as a student (actually Eileen was more like a live-in personal assistant who took voice lessons) and for the next year Eileen shuttled back and forth between Woonsocket and New York, getting some financial help along the way from her brother John, who at the time had a good job designing silverware for a plating company.

While in New York Eileen supplemented her voice lessons with Alcock by studying with a language coach, Charlie Baker, who was the music director at Rutgers Presbyterian Church, New Jersey. Baker eventually hired Eileen as a paid soloist with the church choir at Rutgers Presbyterian and he remained an important part of her early career at CBS, helping her learn the songs for her show, and helping her to get a new voice teacher when the time was right.

But it was Merle Alcock who helped get Eileen’s foot in the door at CBS, securing an audition with Lucile Singleton, the lady in charge of casting for the network. Later, Singleton remembered Alcock’s young student after an opening appeared in the chorus at CBS. She sent for Eileen, who by now had returned to Woonsocket, and heard her sing again, this time with others from CBS in attendance. The result? Well let’s just say that Eileen never had to go back to Rhode Island again for anything other than family visits. She got the job and New York would be her new home.

It was evident, however, that she was too talented to remain buried in the chorus and before long she caught the attention of CBS music director, Jim Fassett, who took a chance on this unknown from New England and built a half-hour variety program around Eileen’s voice as accompanied by the CBS Orchestra under the direction of Howard Barlow. The show, called Eileen Farrell Sings, was rehearsed and recorded during the week and then aired at 11:30pm Sunday night, featuring an eclectic mix of popular and classical selections with Eileen singing both as soloist and in duets with a wide range of performers (including a young Frank Sinatra, once).

One would think that a late Sunday evening show would have a small audience, but it caught on and actually had a six-year run at CBS. The viability of this otherwise dead time-slot was probably due to the U.S. entering World War II in December of 1941, which was, as fate would have it, not long after Eileen’s show debuted. With the whole country now working round the clock, seven days a week, all for the war effort, the listening habits of people had changed dramatically, and Jim Fassett’s gamble on Eileen paid off.

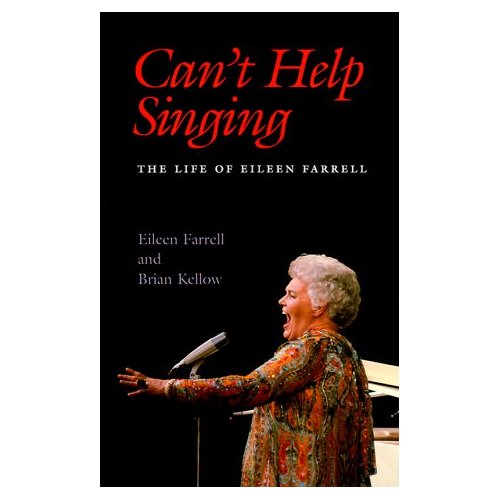

Each week Fassett would pick things for Eileen to sing, giving her a broad repertoire in both the classical and popular realms of music. In addition to her own show, Eileen would sing for other radio programs as a guest artist, both at CBS and on other networks – and she was busy being a young girl in a big city, having the time of her life (even after her family moved into her apartment for a few years before she was married). Yet through it all, Eileen was nonplussed about her sudden rise to fame. In her 1999 autobiography Can’t Help Singing (co-authored with Brian Kellow) she recalled, “I didn’t think I was making art. The radio show was just my job – and a damned good one.”

Voice method book by Eleanor McLellan, Eileen’s second New York teacher (hardcover first edition, Harper & Brothers, New York, 1920)

It was during this time that Eileen finally switched voice teachers after years of needing more technique than Merle Alcock could provide. In 1944, upon the suggestion of her language coach, Charlie Baker, she began a long association with vocal instructor Eleanor McLellan who did much to make Eileen a better singer, improving her breath control and dynamic range so she could sing soft and loud passages with equal effectiveness. Eileen worked on diction with “Mrs. Mac,” as well, but she credits Mabel Mercer, one of the great singers of popular music, who was performing in clubs around town during the war years, as the prime inspiration to her own “getting the story across” approach to song delivery. In fact Eileen became a life-long fan of Mabel’s nonchalant approach and declamatory singing style, and she used that approach as the basis for her own style of interpreting what is currently referred to as “The Great American Songbook.”

Middle Years

By the end of the war Eileen was a Columbia Records recording artist whose career was expanding beyond the world of radio, which was receding in popularity as television took over more and more of the entertainment mindscape. It was during this time that she met and married a New York City policeman, Robert Reagan, with whom she had a son, Robert Reagan, Jr. and a daughter Kathleen Reagan. Shortly after her marriage in 1946, Eileen toured the United States accompanied by pianist George Trovillo, and then she toured South America accompanied by Thomas Schippers, who would later work with Eileen as a world-renown conductor, all under the aegis of CBS’ Community Concerts program.

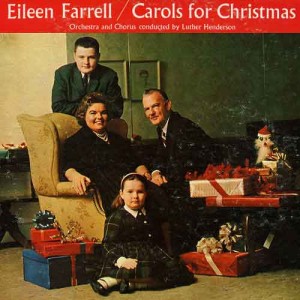

Mr. and Mrs. Robert Reagan and family, on the cover of a Christmas LP released by Columbia in1960 From left: Robbie, Eileen, Kathleen, and Robert, Sr.

Going into the next decade, while raising a family, Eileen managed to keep her career going – with professional management and the assistance of her husband Bob (who watched over her business dealings like a hawk) – making recordings, performing with the newly formed Bach Aria Group and participating in concert versions of operas with symphony orchestras (no costumes or props – just the music). Highlights include: singing the role of Marie in Alban Berg’s expressionist masterpiece, Wozzeck, with the New York Philharmonic, Dimitri Metropoulos, conductor; working with legendary conductor Arturo Toscanini as soprano soloist on his only recorded version of Beethoven’s ninth symphony; and singing the tile role in Cherubini’s Medea at New York’s Town Hall with the American Opera Society, Arnold Gamson, conductor, which many feel was her breakthrough performance.

Her belated full-production debut on the operatic stage was in Tampa, Florida, singing the role of Santuzza in Pietro Mascagni’s Cavalleria rusticana in 1956. She continued singing various other roles with first-rate opera companies across the country, including the San Francisco Opera and the Chicago Lyric Opera, throughout the remainder of the decade, eventually getting an invitation to join the company at the Met in 1960.

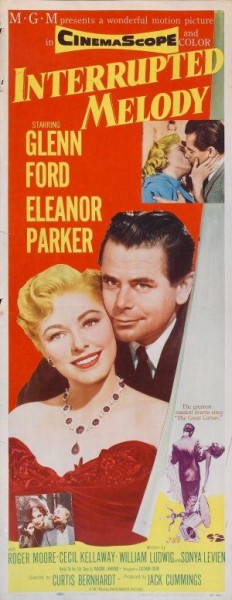

Poster for the movie based on the life of soprano Marjorie Lawrence, for which Eileen provided the singing voice.

Perhaps Eileen’s most widely seen performance took place during this time, but it was literally behind the scenes as the singing voice of Eleanor Parker in the 1955 movie Interrupted Melody, which was based on the life of the polio-stricken Australian opera singer Marjorie Lawrence and for which Parker got an Academy Award nomination as Best Actress.

Eileen and soprano, Marilyn Horne on a 1960s Carol Burnet TV show as the wicked stepsisters in a parody of “Cinderella”

Late Career

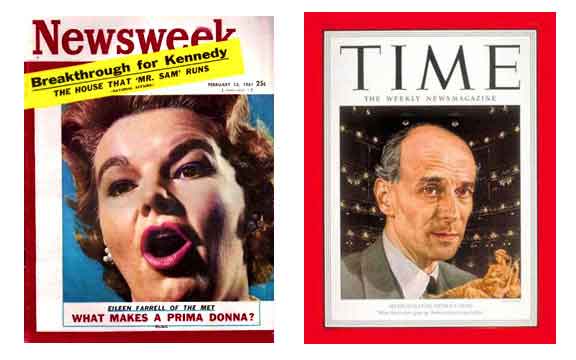

In 1960 Eileen made her debut at the Met singing the title role in Christoph von Gluck’s late 18th century opera Alceste. She got rave reviews but the critics panned the production otherwise, an early indication of her rocky relationship with the Met, especially between her and the Met general manager Rudolph Bing. Despite several successful seasons singing mostly Italian repertoire, including her favorite role as Maddelena in Umberto Giordano’s Andrea Chenier, Eileen was removed from the roster of Met artists in 1966 after she refused Bing’s request for her to take on roles in the operas of Richard Wagner, which Eileen felt would ruin her voice, and after she refused to participate in a production of Wozzeck in English, feeling that since she knew this work in the original German it would be too hard to re-learn this difficult music in a new language. In Eileen’s words, “You didn’t say no to Rudolph Bing twice,” and she never went back to the Met for the rest of her days – not even to see a performance.

Bing’s requests were not totally unreasonable, after all Wagner’s music had been part of Eileen’s repertoire for many years by this time, and many critics thought she had the perfect voice for such iconic roles as Isolde or Brunnhilde. In fact Eileen had just won a Grammy award in 1963 for Best Classical Performance – Vocal Soloist (With Or Without Orchestra) with an album of Wagner, accompanied by the New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein, conductor, which included Brunnhilde’s immolation scene from Gotterdammerung. Yes, Bing’s offer of Ortrud from Lohengren as a major role for that particular season at the Met, sung every three days over the course of a month or so in the usual fashion, would have been a strenuous outing for her voice. And yes, to steer her career in that heavier direction might well have ruined her voice over time. But why wouldn’t Eileen agree just this one time to a full Wagnerian production?

Perhaps it was the image of Wagnerian opera, at least in the productions the Met had in store for her, which represented a line in the sand Eileen was not willing to cross. She didn’t see herself as a larger than life character with Viking helmet, shield and spear singing to the high heavens. She didn’t really see herself as an opera singer at all. Beyond being a wife and a mother, if Eileen Farrell saw any one thing about herself, it would be as a singer of jazz and pop standards like her idol, Mabel Mercer. Besides, everything about opera seemed like a lot of hard work for artistic results that were not necessarily guaranteed – which probably played into Eileen’s refusal to re-learn Wozzeck in English. So as it turned out, Andrea Chenier would be the last complete opera she would sing on stage, and except for an early 1970s album of Gaetano Donizetti’s Maria Stuarta recorded in London with soprano Beverly Sills, it would also be the last complete opera she would ever sing…period.

By the middle of the 1960s Bob Reagan, Eileen’s husband, had already been retired ten years from the New York police force and he had grown weary of city living. He wanted to move out to the country and after a lot of research he choose Londonderry, New Hampshire due to its low property tax rate. Eileen went along with this move even though it made it more difficult to get to her New York gigs. Their son Robbie enrolled in the University of New Hampshire and their daughter Kathleen went to the local high school, and even though Eileen found it hard to be away from the center of things, the Reagans stayed put in New Hampshire until their children were out of their respective schools.

At this point Eileen was no long under contract with Columbia Records due to a disagreement between her husband and the label over the royalty rates in her contract renewal, and with her time at the Met now ended, she found herself performing less and less. However, in 1971 after her son was out of college and had been drafted into the Air Force and sent to Viet Nam, an opportunity arose for Eileen to join the faculty at the music school of the University of Indiana, Bloomington. In a move remarkably similar to that of her parents when they taught college in Storrs, CT, Eileen and Bob moved to Bloomington. Kathleen transferred from Emanuel College, Boston to go into the pre-med program at IU, and after returning from Viet Nam Robbie entered law school there as well.

Eileen continued teaching at IU for almost ten years, coaching singers in opera performance and also instituting a very popular course in jazz singing. She had disagreements however with the way the curriculum for opera was being run in that it seemed to push students into roles for which they weren’t vocally ready, and in trying to change this approach she seemed to be making more enemies than friends among her IU voice faculty colleagues. In the fall of 1980 Eileen quit her job at IU after getting reprimanded by the head of the voice faculty for speaking her mind in the campus newspaper about what she saw as an abuse of the students’ voices in the opera program. But she had other reasons for leaving IU. Earlier that year she recorded a track for Frank Sinatra’s Trilogy album, singing a duet version of “For The Good Times,” which was well received. This got Eileen excited about singing again and was an incentive to leave full time teaching behind.

Eileen reunited with Frank Sinatra for one song on this album, which proved to be something of a career comeback for her

Eileen and Bob decided to move from Indiana to Maine, where many years before they had a vacation home. It was during this move that Eileen injured her knee, which limited her public performances for several years. She did manage to teach some master classes at the University of Maine, Orono, during this down time, and she made a return to the airwaves as well, hosting a show on contemporary singers of “the great American songbook” for National Public Radio. But in 1986 her dearly beloved husband, Bob died from complications after surgery to remove a tumor from his lungs. Eileen quit singing altogether for a time after Bob’s death, until a call from Leonard Bernstein to sing at an AIDS benefit with him accompanying her on the piano convinced Eileen to gradually start sharing her gift with the world again. And although she didn’t do a lot of public performances in her later years she did record a series of albums of American popular songs on small independent record labels, the last being Love Is Letting Go in 1995 on the DRG label.

Eileen’s last years saw her moving to New Jersey to be near Kathleen, her daughter, who had taken a position at the radiology department at Columbia-Presbyterian Hospital in New York. She spent her time visiting friends, seeing favorite singers perform cabaret in the city, and working on her autobiography, with Brian Kellow, an executive editor of Opera News magazine. Northeastern University Press, Boston, published the completed book, Can’t Help Singing: The Life of Eileen Farrell, in 1999. This proved to be the last hurrah, for within a few years Eileen’s health deteriorated and her family had to place her into a nursing home where she died in 2002.

Conclusion

Eileen always considered Woonsocket, RI her hometown – even though she grew up in Connecticut and lived in the New York City area during the height of her professional years. And if you can accept that Eileen Farrell was indeed a Rhode Islander, at least by inclination, you could also say that she’s on the short list of Rhode Islanders who get name-checked in a Cole Porter lyric.

If Ginny Simms and Georgia Carroll

And Dinah Shore and Eileen Farrell

And Mildred Bailey

Can night and daily

Impress the public so

Then I too can wa-hoo

And sing on the radio!

“Big Town” from Seven Lively Arts (1944)

Ironically Eileen rarely sang any Porter songs herself, much preferring the songs of Rodgers and Hart and Harold Arlen. But it shows, if any more proof was needed, Eileen’s effect on the American public during her early career. A career that took off so successfully, so quickly, it was as much of a surprise to Eileen as it might have seemed to someone as worldly and urbane as Cole Porter. The lyrics of Porter’s little song also imply that Eileen was one of a number of female singers on the airwaves during the war years, no doubt providing a sense of comfort to the service men in uniform.

That she wasn’t a bigger star was mostly due to her commitment to her family – she frequently turned down performances if they took her away from home for too long. And though she has always been credited with being an intelligent actress with a special gift for bringing out the meaning of the words through her musical articulation and phrasing, Eileen‘s heavy physicality was, in her own estimation, not conducive to starring in Broadway or Hollywood musicals. She gave the same reason for not actively pursuing operatic productions during the early part of her career, concentrating instead on song recitals, concert work, and recordings. Perhaps she did not want to become a “fat lady singing opera” caricature. In any case, she wasn’t crazy about the amount of work and the backstage politics that are part and parcel of many opera productions. Eventually, however, the demand for her talent was such that it drew her little by little into full opera productions for which she received widespread critical acclaim. Yet she had the self-awareness to speak up and say no to productions that she felt were wrong for her, as was the case toward the end of her tenure at the Metropolitan Opera.

Despite not flying as high as her gift would warrant, this songbird, who began her professional journey from her grandfather’s humble home on Manville Road, was indeed a diva – albeit a homespun diva – proud of her New England Irish Catholic heritage, quick of wit, and free of speech. (According to Beverly Sills, who was a good friend of Eileen’s, “the woman sings like a goddess and talks like a sailor.” A description Eileen refutes – somewhat – in her autobiography.) But above all else Eileen Farrell was amazingly versatile of voice, and that voice conveyed her love of music to all, making her a worthy addition to the Rhode Island Music Hall of Fame.

REFERENCES & RESOURCES

Books

Eileen’s autobiography Can’t Help Singing: The Life of Eileen Farrell, co-authored with Brian Kellow (Northeastern University Press, 1999) is the main source for events in her life.

Beverly Sill’s autobiography, Beverly, co-authored with Lawrence Linderman (Bantam Books, 1987) gives slightly differing accounts of some of the events mentioned in Eileen’s book. But it does serve to confirm the occurrence of the events themselves.

Web Biographies

American National Biography Online:

http://www.anb.org/articles/18/18-03840.html

Britannica Online Encyclopedia:

http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/202118/Eileen-Farrell

This article mentions a 1963 Grammy award winning pop album Songs not mentioned in Eileen’s autobiography or any discographies. It probably is a mistaken reference to the Bernstein conducted classical recording that includes Eileen singing Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck Songs, which did receive a Grammy award in 1963 for best classical vocal performance.

1963 Grammy Awards:

http://www.metrolyrics.com/1963-grammy-awards.html#ixzz26an7dlOK

Cantabile:

http://www.cantabile-subito.de/Sopranos/Farrell__Eileen/hauptteil_farrell__eileen.html

this is a brief biography and discography that includes a good analysis Eileen’s voice.

Encyclopedia of World Biography:

http://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Ca-Fi/Farrell-Eileen.html

Wikipedia entry:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eileen_Farrell

Woonsocket Patch:

http://woonsocket.patch.com/articles/eileen-farrell-from-woonsocket-to-the-grammy-awards

An interesting Daytona Beach newspaper article focusing on Eileen Farrell’s home life around the time of her Metropolitan Opera debut:

http://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1873&dat=19601203&id=sZYeAAAAIBAJ&sjid=gMwEAAAAIBAJ&pg=721,670591

Video

Two part 1993 interview with Charlie Rose:

Part One – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YPqm9MFmHx4

Part Two – http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xwwwK-MNdNI

Eileen singing the Liebestod from Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, date and location unknown – possibly an American TV broadcast from the 1960s –

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Etw5sdLa0Qg&feature=related

Eileen singing Leonard Bernstein’s “Some Other Time” accompanied by the composer at the late 1980s AIDS benefit that got her singing again after her husband died. You get the rare opportunity to hear Lenny sing here as well:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A9bLMqztl0Y

DISCOGRAPHICAL INFORMATION & RESOURCES

Bad news first…

To date (Autumn, 2012 at this writing), no detailed, comprehensive, complete discography has ever been assembled for Eileen Farrell’s recording career. With live and studio sessions spanning seven decades (not to mention the audio artifacts of her radio and television appearances), an undertaking such as this would be a monumental task, well beyond the scope of the Rhode Island Music Hall Of Fame Historical Archive team at this time. (And, apparently, beyond the scope of everyone else, too! Even her official autobiography only includes a selected discography.)

16 inch/16 rpm acetate of a live Farrell broadcast for the popular “Prudential Family Hour” radio program from the late 1940s. The Original Old Radio Company is in the process of digitizing this series for CD and .mp3 download sales

The good news, however, is really good!

The vast majority of Eileen’s recorded output is in print on CD (compact disc) and available for downloading from all major internet music outlets.

The incredible sales successes she achieved as a recording artist (thanks to her vast mainstream popularity beyond the scope of the classical music and opera communities) coupled with the historical importance of her work virtually guarantees that her work will be available in perpetuity. The existence of the download component in availability bears testament to the fact that her music will be easily obtainable even after the inevitable demise of “round media.”

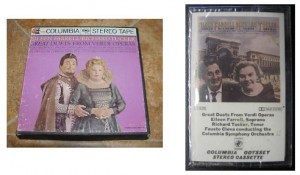

The great Farrell-Tucker duets album on 7″ reel-to-reel from the 1960s next to the 1970s cassette reissue. This album is still available on CD and as a download

A simple query on any web search engine will point you to dozens (perhaps hundreds) of titles currently available at retail and internet outlets for the purchase of CDs or .mp3 files. (For instance, amazon.com, cduniverse.com and iTunes have just about everything and other sites will help you fill in any gaps.)

All of her major operatic roles as well as her special projects (the Verdi and Puccini arias albums, for instance) are currently available as are all her jazz and pop recordings for Bethlehem Records, Columbia Records and her final series of “great American songbook” albums at the end of her career.

For collectors, the news is just as good! Eileen was one of the best-selling classical artists of all time meaning that there are literally millions of copies of her records out there in their original configurations (78s, 45s, tapes, LPs, CDs). So, if you’re looking for original pressings, again, you need go any further than a simple web search to turn up affordable copies. (Just try eBay, Music Stack and Gemm and you’ll see what I mean!)

Eileen’s 78 rpm collection of Irish songs from the 1940s is one of her only albums which has not been reissued. It was a best seller, however, and is easily obtainable on the internet in its original configuration

As you read this entry, her autobiography, or any other reference source, you will find that any recording that looks like it might be of interest to you is more than likely easily available in some form.

Hopefully, along the way, the RIMHOF Historical Archive (or some other entity) will find the resources to compile the complete discography Eileen’s career so richly deserves, but in the meantime, it’s pretty much all out there and easy to find. Happy hunting!

– Rick Bellaire, RIMHOF Archive Director, September, 2012